When future historians try to understand what ‘trafficking’ meant in the first 20 years of the 21st century, I hope this memoir gives them pause. Recording how my questions about migration from 25 years ago coincided with the rise of a thing called trafficking as major social issue, this piece is both personal and political.*

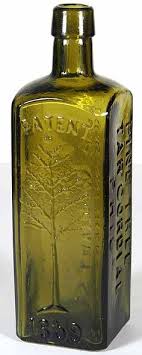

Snake Oil

Swindle, chicanery, skullduggery, con. There’s no one perfect word to describe how trafficking came to be hailed as one of the great problems of our time. Excess in rhetoric has known no bounds, with campaigners saying theirs is the new civil-rights movement and claiming there are more people in slavery today than at any time in human history, amongst ever-intensifying hyperbole.

And there was me thinking it was about folks wanting to leave home

to see if things might be better elsewhere.

The outcry had begun in insider-circles when I stumbled onto the scene in the mid-1990s, but I didn’t know the lingo or even what ideology was. Novels were my reading, not social theory. I hadn’t ‘studied’ feminism but felt myself to be part of a women’s movement since the early 1960s. I believed I was asking reasonable questions about a puzzling social phenomenon and refused to be fobbed off with explanations that made no sense. My trajectory as a thinker happened to coincide with a piece of governmental legerdemain that switched the topic of conversation from human mobility and migration to organised crime, like peas in a shell game.

At the time I was thinking about how so many, when faced with adversity, decide to try life in new places. I was not specially disrespectful of laws, but, like most migrants, didn’t feel that crossing borders without paper permission was a criminal act. I had no preconceived notions about prostitution; the women I knew who sold sex, poor and less poor, understood what they were doing.

For a while I had a job in an AIDS-prevention project in the Caribbean and was sent to visit parts of the island known for women’s migrations to Europe, where they would work as live-in maids or prostitutes. I visited small rural houses where daughters living abroad were money-sending heroes. At a film showing migrant women being beaten up by Amsterdam police, campesina audiences scoffed: their friends and relations in the Netherlands told the opposite story. A funding proposal I worked up for improving the experiences of migrants was returned with everything crossed out except ‘psychological help for returned traumatised victims’, an element I’d never included in the first place.

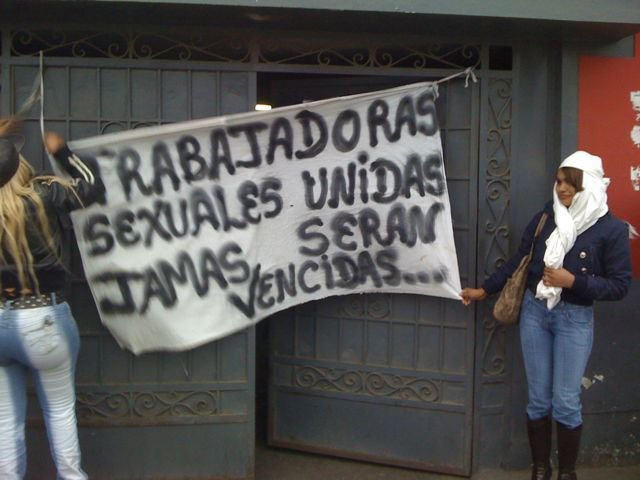

At a daylong event in Santo Domingo that was organised by black bargirls who called themselves sex workers, I sat in the last row. After a series of testimonies by the women and expositions by local legal experts, a speaker appeared who was said to have flown in from Venezuela. Addressing herself to the women in the first row she said ‘You have been deceived. You are not sex workers; you are prostituted women’.

At a daylong event in Santo Domingo that was organised by black bargirls who called themselves sex workers, I sat in the last row. After a series of testimonies by the women and expositions by local legal experts, a speaker appeared who was said to have flown in from Venezuela. Addressing herself to the women in the first row she said ‘You have been deceived. You are not sex workers; you are prostituted women’.

I was horrified: How could she be so rude to her hosts? Someone said she was a member of the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, but I didn’t know what that meant. From my place at the back I couldn’t see the bargirls’ reaction, but no angry words or protest ensued, perhaps because at that somewhat formal event a certain middle-class respect held sway.

A couple of years later, working in Miami as a secretary, I got on the Internet. When I finally learned how to search properly, I connected to a forum of escorts and activists who seemed to be on my wavelength about selling sex. Advocates of rights, they spoke about their personal experiences, and while they didn’t share the migration context, their feelings about this livelihood were the same as those of migrant women.

So now I was really puzzled: Where did the disparity of ideas about prostitution come from? What was the uproar about? What about the women I knew? No one was talking about migrants. When I set out to read about them, I found nothing at the public library.

To cut the story short, I ended up in a Master’s programme in something called International Education, which led to my first visit to a university library, call-number for prostitution in hand. Books with this number stretched from the top shelf to the bottom and up and down again into the distance. Beginning at the first book I began to read, but it didn’t take long for the books to seem indistinguishable. I began to riffle though tables of contents and key chapters, looking for discussions of my common-sense questions. When I found nothing, I wondered how there could be so many books so short on actual information. No one like my friends was ever mentioned, migrant or not. Something strange was going on.

For fieldwork purposes I proposed a short ethnographic stint in Spain, where I’ve often lived, amongst migrant women selling sex. One application for funding got me onto a shortlist, but at the interview by a committee, a political science professor slapped my proposal impatiently. ‘These women’, he jeered. ‘How do they get there?’ ‘In airplanes’, I replied.

My limited but grounded experience was whole discourses away from how such academics had begun to talk. Later I was told he was acquainted with Kathleen Barry, whose books hating prostitution had figured in my reading.

This was my first experience of bias based on my having framed the subject wrong: rather than Migrant Women Selling Sex, my proposal should have been titled Trafficked Women. I know this now, but at the time I was only mystified.

@rigels, Unsplash

Soon after, I was invited to speak at an event for International Women’s Day to be held in the community centre of a small New England town. Someone had to drive me hours through heavy snow to get there, but upon arrival we were told my name had been removed from the agenda. Some influential person, probably an academic, had been outraged that I’d been invited, but I never met them, knew their name or received an apology. This was my second experience of bias against my way of thinking.

After that, I lost count.

In 1998, I was invited to join the Human Rights Caucus at meetings to draft protocols to the UN Convention against Transnational Organised Crime. My ideas were welcome to this group, but I said no, because I still believed there was a misunderstanding. I thought there must be women I hadn’t met who could be understood through this concept of trafficking, and since I wasn’t studying them I saw no reason to get involved.

But as time went on and I presented my work here and there, I realised we were all talking about the same thing: women who leave home and make a living selling sex, in a variety of circumstances. But where I was describing how they try to take control of their lives, others were denying them any part in their fate. In the process of defining women who sell sex as victims, all differences in experience were being erased. I considered the result to be the antithesis of interesting and meaningful intellectual work.

I had set out to understand the disconnect between what I saw around me, amongst my friends and increasing numbers of acquaintances who were selling sex and how they were discussed by outsiders. At the end of the Master’s degree I had inklings of what was going on but hadn’t answered my original question: Why were women who opted to sell sex such a source of discord? And the corollary: Why were so many vowing to save women from prostitution?

Rather reluctantly, I pursued these as a doctoral student in Cultural Studies in England, but I spent several years in Spain doing the field work. My research topic was not migrant women, since there was no mystery to me about what they were doing. Instead, my subject was those social actors who professed to help migrants and sex workers, in governmental, NGO and activist projects. They were my mystery. When I started in 1999, none of them were talking about trafficking, but polemic about prostitution was ubiquitous.

In 2000, the editor of a migration-oriented journal in Madrid invited me to write about migrants who sold sex, sin polémica (without polemic), because by now outraged ranting was the only tone heard in public. By this point I was observing in a consciously anthropological fashion, so her requirement suited me. The resulting article, Trabajar en la industria del sexo (Working in the sex industry), led to a high official’s infiltrating me into an event held by the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, to spite an abolitionist rival. Although I had no intention of making my presence known, I did attend, and for one long day listened to the ravings of some of the world’s most well-known anti-prostitutionists.

In 2000, the editor of a migration-oriented journal in Madrid invited me to write about migrants who sold sex, sin polémica (without polemic), because by now outraged ranting was the only tone heard in public. By this point I was observing in a consciously anthropological fashion, so her requirement suited me. The resulting article, Trabajar en la industria del sexo (Working in the sex industry), led to a high official’s infiltrating me into an event held by the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, to spite an abolitionist rival. Although I had no intention of making my presence known, I did attend, and for one long day listened to the ravings of some of the world’s most well-known anti-prostitutionists.

I won’t forget how Janice Raymond narrowed her eyes and dropped her voice when denouncing those who disagree with her fanatical abolitionism: ‘There might even be some of them in this room’, she said.

I backed against the wall where I was standing, wondering if she knew I was there. Later they trooped into a luxurious salon for smug feasting on elegant canapés and wines, inside the hyper-bourgeois Círculo de Bellas Artes.

When the Palermo Protocols were published I saw the human-rights group had managed to limit the damage, but I was glad I had decided to stay away from meetings to draft them. While trying to understand the humanitarian impulse to ‘help’ the poor I had appreciated Cynthia Enloe’s work showing how ‘womenandchildren’ are treated as an indistinguishable mass of helpless objects. Now here these objects were, enshrined in a trafficking protocol that scarcely acknowledged women as migrants, while migrant men exercised agency in the smuggling protocol.

It was soon obvious to insiders that the situating of migration- and sexwork-issues within the ‘organised crime’ framework was a fatal event that would determine the nature of all conversation afterwards. Many who believed distinctions between smuggling and trafficking could be maintained and the trafficking concept kept within bounds soon threw up their hands. Ever more activities were said to be trafficking, causing numbers of presumed victims to skyrocket.

My counter-narrative formed part of a calm and conventional report on migrant women’s jobs in Spain carried out by a collective of Madrid sociologists glad to have someone to do the sex-work section (2001). A few years later Gakoa published my various writings so far in a book called Trabajar en la industria del sexo, y otros tópicos migratorios (2001, Working in the sex industry, and other migration topics). I was reaching an audience skeptical of the news they were being fed in mainstream media about migrant women.

Trafficking became a big-time crime issue not because of its truth but because it served governments’ purposes. The interminably warlike USA loved a reason to go after bad men of the world on the excuse of saving innocent women. European states got justification to tighten borders against unwanted migrants. The UK could pretend it was going to be the new leader of anti-slavery campaigning just as their empire comes to an end. The UN was authorized to set up numerous new programs and initiatives. A range of other governmental entities benefited; Interpol and many police services were able to expand to new areas of ill-informed expertise.

And then the NGO sector began to sign up to this infantilisation of women, just as if we were living hundreds of years ago, when East End social workers set out to raise the fallen women of London. Even Hollywood actors jumped on the bandwagon as ambassadors claiming to be ‘voices for the voiceless’. The urge to Rescue was mainstreamed.

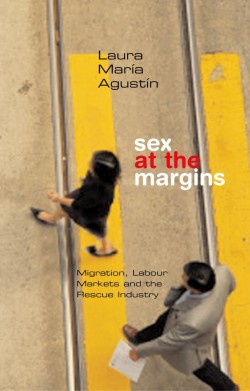

Meanwhile, I finished the PhD and put the thesis away. For several years I ignored a contract I had signed with Zed Books to publish, because I’d answered my own questions and didn’t imagine others would be interested. Eventually I changed my mind and edited the thesis to become accessible to more readers. When Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labor Markets and the Rescue Industry came out in 2007, it spoke to a growing social controversy and, rather than die the usual quick death of even quasi-academic volumes, has continued to sell, as relevant now as it was 13 years ago – alas. This was the birth of the term Rescue Industry. Mainstream media were interested; I wrote for some established news sources.

By 2010, when the BBC World Service invited me to speak at a televised debate on trafficking at an event sponsored by Madame Mubarak in Egypt, anti-trafficking had taken over the airwaves. But 50 minutes called ‘debate’ needed drama, and so far the panel was composed of guests all singing the same Rescue tune. I demurred: Why would I subject myself to such nonsense? Everyone would hate me – No. Then they said I could bring a friend, and I gave in, ending up on a stage in the Temple of Karnak. I managed to keep a straight face at the piffle flowing forth until Siddharth Kara’s pretence of expertise made me laugh out loud, causing Hollywood actors Mira Sorvino and Ashton Kutcher to rise from their seats in the audience to deplore me and deplore the BBC for having me. The meaning of the word ‘debate’ had escaped them. Symbolic, really.

Nothing that has happened since has changed my mind about the Protocols. A complex situation was deliberately obscured by governmental actors who set up a straw man so frightening scads of educated liberal folks were bamboozled, and through heavy financing and institutionalisation of programmes the fraud continues. I do not refer here to what is called moral panic, though that helps explain how the general public got caught up in the frenzy. I’m referring to the cynical selection of a fake tragic and terrifying cause as governmental policy.

Mechanisms to frame policy based on lies are not uncommon: a similarly egregious recent case involved ‘weapons of mass destruction’ that didn’t exist. And just as hardcore war was waged based on that lie, softcore belligerence has been endlessly launched at migrants and women who sell sex, via the claim that everyone who facilitates a trip is a criminal, everyone who buys a trip is a victim and every prostitute must be rescued. Embarrassing mainstream pundits like the New York Times’ Nicholas Kristof elide all kinds of commercial sex with trafficking, in an undisguised campaign against prostitution that allows them to take imperialistic jaunts such as live-tweeting brothel raids in Cambodia (2012), shenanigans moral entrepreneurs carry out in an effort to look like heroes.

The actual earthly problems behind all this derive from poor economies and job markets that spur people to go on the move in search of new places to work. Sometimes home-conditions are direr than usual; sometimes there is gang conflict, war or natural disaster. At times societies are so unjust that those persecuted for beliefs or personal characteristics feel compelled to abandon them. In all these cases, when they illegally move into other countries, anti-foreigner sentiment, underground economies and social conflict flourish.

Which alternative policy-frameworks might have described this complexity, and which policy responses could have ensued, had honesty prevailed? In countries of origin, better distribution of wealth via economies that provide jobs with wages that can be lived on. In destination countries, an overhaul of government accounting so that more jobs are included in the formal sector, coupled with migration policy that allows more work-permits allotted for jobs not defined as ‘highly skilled’.

There are challenges here, but the ideas stick to the ground where ordinary people pay other ordinary people to help them travel, get across borders without visas and get paid jobs without holding residence or work permits. This includes women who opt to at least try selling sex.

Which mountebanks sold the snake oil first? Who suggested laws against trafficking were the way to solve migration problems? Moral entrepreneurs who cry about wicked foreigners are never scarce in times of stress. By the 1990s, scare-tactics increasingly turned to bogus estimations about illegal migration. Statisticians, tech-personnel and macroeconomists professed to provide data on how many criminals move how many victims around, with fancy new graphics and obfuscating equations.

None could have any real idea how many undocumented migrants work in informal-sector employment; they are extrapolating and estimating, often based on crude and random police reports. More recently, projects of surveillance using algorithms claim to tell us how many females are snapped up by sex-predators on the web. This disinformation was and continues to be promoted by a variety of opportunists for their own ends. The nonsense appears to have no end, as even certain emojis used in social media are banned as prurient.

It is not difficult to understand why politicians and government employees decided to buy the miracle product of trafficking: they stood to gain money and power. Trafficking narratives present a struggle between Good and Evil in which masculine men are protagonists, and a women’s auxiliary takes up the veil of Rescue. As time goes on, terrorism and war are mentioned more often, with victims a kind of collateral damage that justifies more programming and more police.

Ten years into the skullduggery I had a request for an interview from a young woman studying journalism and wanting to support sex workers’ rights. We met in a small old pub in Islington where, after the usual niceties, she put her question in a pleading tone. ‘Are you sure it’s not true?’ ‘What?’ ‘There aren’t millions of women trafficked into sex-slavery?’

I pointed towards the busy City Road. ‘Do I think lots of women are chained to radiators in flats out there? No. But I’m sure there are women who considered that coming to London to sell sex was a feasible way to solve their problems, and some will have paid a lot of money for help getting here’.

I have since 2008 done public education from a blog and other social media. By 2013 the disconnect between what mainstream news was feeding the public and what I was saying led to so many requests for clarification that I published Dear Students of Sex Work & Trafficking. I deconstruct Rescue-Industry claims, debunk research methods and statistics and track the progress of Law-and-Order projects to surveil sex workers and other undocumented folk.

In the 17th year after the Protocols I published a novel, hoping for a better way to tell the truths underneath bamboozling policy. Set in Spain amongst migrants and smugglers, many undocumented and selling sex, The Three-Headed Dog is a fiction version of Sex at the Margins, to be enjoyed as story and glimpse of reality.

In the 20 years since the Protocols were published, nothing has improved for migrants, sex workers or teen runaways. Things have picked up greatly for smugglers, though.

Sometimes Yoko went down to the port to watch the ships sail off to places she only wished she could go, 1964, Michael Rougier, Life Pictures/Getty Images

Works cited

Agustín, L. (2000). Trabajar en la industria del sexo. Ofrim suplementos, Número 6, dedicado a Mercado laboral e inmigración.

Agustín, L. (2001). Mujeres migrantes ocupadas en servicios sexuales. In Colectivo IOÉ (Ed.), Mujer, inmigración y trabajo (pp. 647–716). Madrid: IMSERSO.

Agustín, L. (2005). Trabajar en la industria del sexo, y otros tópicos migratorios. San Sebastián: Gakoa.

Agustín, L. (2007a). Sex at the margins: Migration, Labour Markets and the Rescue Industry. London: Zed Books.

Agustín, L. (2007b). What’s Wrong with the Trafficking Crusade? The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Agustín, L. 2012a. A man of moral sentiments. Review of Siddharth Kara, Inside the Business of Modern Slavery, H-Net, February.

Agustín, L. 2012b. The soft side of imperialism. Counterpunch, 25 January.

Agustín, L. 2013. Dear students of sex work & trafficking. 25 March.

Agustín, L. 2017. The three-headed dog. Amazon, ASIN: B01N2V79UC.

BBC World Trafficking Debate, Luxor, Egypt. 2010. The full videos have been removed, probably because of the Mubaraks’ disgrace, but the event and line-up are visible.

Highlights of the debate are available, thanks to Carol Leigh.

Many of my other publications, including those published in Spain when I was living in Madrid and Granada, can be got from the top menu of this website.

A somewhat different version of this piece appeared in a specal issue of the Journal of Human Trafficking, Palermo at 20, written at the invitation of Elzbieta Goździak. The present version was also published by Public Anthropologist.

*Photo: David Clode, Unsplash

–Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist