Every reviewer has to mention a different defect in the book under review: That was my conclusion when reviews of Sex at the Margins were proliferating. Some of the defects pointed to said more about the reviewer than the book, like the English academic who dismissed the research because it had taken place in Spain. I laughed a lot at that one. If you’re interested in migration and globalisation then nation becomes a funny category.

Every reviewer has to mention a different defect in the book under review: That was my conclusion when reviews of Sex at the Margins were proliferating. Some of the defects pointed to said more about the reviewer than the book, like the English academic who dismissed the research because it had taken place in Spain. I laughed a lot at that one. If you’re interested in migration and globalisation then nation becomes a funny category.

The other day I was interviewed by an investigator interested in undocumented migration in The Three-Headed Dog. We met in a blue bar and drank from stemmed glasses. She agreed I may publish a few points of our conversation, on the subject of place, location and nationality. Her name is Zelda.

Zelda: Why did you situate The Three-Headed Dog in Spain? Is the plot special to the Costa del Sol? Or could it be moved to Britain or Italy or the state of Florida?

Zelda: Why did you situate The Three-Headed Dog in Spain? Is the plot special to the Costa del Sol? Or could it be moved to Britain or Italy or the state of Florida?

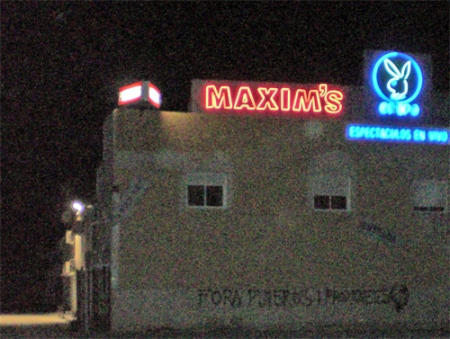

Laura: Spain has long been part of my own life and I lived in Granada while I was reading and doing fieldwork for and then writing what became Sex at the Margins. The Costa del Sol is one of the most fluid and confusing places I know, full of every sort of human mobility, and therefore appealing to me.

The stories in The Dog could be moved in terms of every important concept: How migrants reason and feel about what they’re doing and the sorts of networks they live in. The way they have to look for jobs and housing, the existing in and crossing out of social margins. Those are universal dynamics for undocumented migrants anywhere in the world. But margins feel different according to the terrain and the historical moment.  If the scene were set elsewhere plot-mechanics would vary according to local laws and policing, cultural ideas about sex and women’s mobility, the availability of black-market jobs and the ease of getting out if things go wrong. If there is a coast, boats are an option. Sometimes trains are easily hopped.

If the scene were set elsewhere plot-mechanics would vary according to local laws and policing, cultural ideas about sex and women’s mobility, the availability of black-market jobs and the ease of getting out if things go wrong. If there is a coast, boats are an option. Sometimes trains are easily hopped.

Zelda: What about the migrants, are they interchangeable? Could the group of Dominicans on the airplane just as well be Chinese? What about the young Romanian smuggler, could he be Greek? Could Polish Tanya be French? Does anything about nationality matter?

Laura: The human responses portrayed are not unique to any nationality, but some of the mechanics of migration would have to change if you were to make arbitrary switches. For example, Tanya might humanly be French, but she’d be less likely to set up a cleaning service in Madrid. Or the Dominican club-owner, Carlos: If he were Chinese he might certainly run a hostess-bar, but it would be in another part of Madrid, and have a different style, perhaps with gambling, and would the protagonist Félix plausibly have become his close friend?

The key to making the story work in any particular place is knowing how migrant networks function and the patterns that have developed based on (1) the possibility of getting visas to other countries and (2) colonial and other dependency/linguistic histories that lead to family relationships. For instance, Brazilians have visa-freedom to travel to Portugal, which is part of Schengen territory, meaning they cross easily into Spain and rest of Europe. Dominican women have a long history as maids and sex workers in Spain – over generations. These are migrations that give meaning to the word transnational.

The key to making the story work in any particular place is knowing how migrant networks function and the patterns that have developed based on (1) the possibility of getting visas to other countries and (2) colonial and other dependency/linguistic histories that lead to family relationships. For instance, Brazilians have visa-freedom to travel to Portugal, which is part of Schengen territory, meaning they cross easily into Spain and rest of Europe. Dominican women have a long history as maids and sex workers in Spain – over generations. These are migrations that give meaning to the word transnational.

Zelda: Can migrant women become sex workers anywhere, whether there’s some kind of regulated sex work or not?

Laura: The two jobs available everywhere to undocumented women are maiding and sex work, but if the plot were picked up and put down in Hong Kong, say, then adjustments would be needed to the kinds of sex businesses where migrants are likely to get employed. And to take up any kind of sex work without knowing the local context and laws, without knowing a few people on the inside, who can give informed advice, is highly risky. This is why there are roles for ‘protectors’ in the migration process, and most of them are not monsters. The plot would have to reflect this.

Zelda: What about racism? Aren’t some countries worse in that way? Wouldn’t that make a big difference to where you set the story?

Laura: In the book, several of the Dominicans reflect on racial hierarchies that affect them in Spain, including those that give some dark ethnicities more cachet than their own. All cultures have ideas and prejudices about Others. But also mixing and hybridity are everywhere, even if more in some places than in others. The consequences are always the same: natives feel threatened, some promote xenophobia, governments talk about tightening borders. But there are colonial histories that can make natives feel that some foreigners are closer to themselves than others, whether their skin is blacker or not.

Laura: In the book, several of the Dominicans reflect on racial hierarchies that affect them in Spain, including those that give some dark ethnicities more cachet than their own. All cultures have ideas and prejudices about Others. But also mixing and hybridity are everywhere, even if more in some places than in others. The consequences are always the same: natives feel threatened, some promote xenophobia, governments talk about tightening borders. But there are colonial histories that can make natives feel that some foreigners are closer to themselves than others, whether their skin is blacker or not.

Zelda: So colonial things, like language. Dominicans who go to Spain already speak Spanish, which has to be an advantage, right? What would happen if you changed the group on the plane to Chinese? Isn’t the whole thing much harder if it’s a new language?

L: Not as much as you imagine. Félix visits a Chinese migrant who runs a big variety store and who stands up well to extortion attempts because she has community behind her. Migrants come via networks whether they are legal or not. And migrants from different communities often communicate more easily with each other in the new language, because they all speak more slowly or with a common vocabulary. Then, too, sharing language can work the other way: when Dominicans speak, Spanish listeners know where they are from and bring negative cultural baggage to bear.

L: Not as much as you imagine. Félix visits a Chinese migrant who runs a big variety store and who stands up well to extortion attempts because she has community behind her. Migrants come via networks whether they are legal or not. And migrants from different communities often communicate more easily with each other in the new language, because they all speak more slowly or with a common vocabulary. Then, too, sharing language can work the other way: when Dominicans speak, Spanish listeners know where they are from and bring negative cultural baggage to bear.

Z: The Costa del Sol has all kinds of ethnic groups in it, but you mention places like a Danish church and the urbanizaciones where everyone living there is the same nationality. Don’t a lot of migrants stick to their own kind? Isn’t there insularity among other Europeans who have made second homes on the coast?

Laura: There is, but not forever for everyone. Europeans trying to settle and start businesses feel ambivalent about what they’ve left behind and anxious to hold onto their national selves. You see signs in Swedish or German, shops with food items imported so other cuisines can be maintained. But over time things loosen up for a lot of people, they become more curious and less fearful, they make new connections and cultures blend. And for some people, being in a mixed place with a shifting sense of belonging becomes interesting. They don’t find it so easy to answer the question Where are you from? It’s more about This is where I am now. I wrote about this kind of cosmopolitanism among sex workers in Leaving Home for Sex, many years ago.

Laura: There is, but not forever for everyone. Europeans trying to settle and start businesses feel ambivalent about what they’ve left behind and anxious to hold onto their national selves. You see signs in Swedish or German, shops with food items imported so other cuisines can be maintained. But over time things loosen up for a lot of people, they become more curious and less fearful, they make new connections and cultures blend. And for some people, being in a mixed place with a shifting sense of belonging becomes interesting. They don’t find it so easy to answer the question Where are you from? It’s more about This is where I am now. I wrote about this kind of cosmopolitanism among sex workers in Leaving Home for Sex, many years ago.

For more about The Three-Headed Dog, a noir/mystery novel on sexwork and migration, see

Sexwork and Migration Mystery

Melodrama and Archetypes

Jobs in the Sex Industry

-Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist

During the 20 years I’ve been consciously thinking about migration and prostitution, sex work and the sex industry, I have rarely seen such a bad portrayal of these deep and complex topics as in

During the 20 years I’ve been consciously thinking about migration and prostitution, sex work and the sex industry, I have rarely seen such a bad portrayal of these deep and complex topics as in