Le sexe en tant que travail et le travail du sexe

Le sexe en tant que travail et le travail du sexe

Ouvrage, traduction par Etienne Simard

Une version anglaise de ce texte a été publiée dans Jacobin Magazine (2012), The Commoner (no 15, 2012) et Arts & Opinion.

Par LAURA AGUSTÍN

Publié le 7 décembre 2020

Il y a quelques années, on m’a demandé de rédiger un texte pour une édition spéciale de la revue The Commoner qui portait sur le travail du care et les communs (coordonné par Silvia Federici et Camille Barbagallo). Contrairement à ce qui était d’usage à l’époque pour les personnes qui étudient le travail de soin et de reproduction, elles tenaient à y inclure le travail du sexe. Elles m’ont posé une série de questions, dont certaines auxquelles je n’avais pas l’habitude de répondre. Leur langage marxien d’un certain type, que je ne parle pas couramment, faisait en sorte que je devais continuellement demander des éclaircissements. Enfin, leur édition spéciale est parue en 2012, dans lequel on retrouvait le présent texte. Ce dernier a également été publié dans Jacobin au cours de la même année. Le voici donc maintenant publié pour la première fois en français. Il commence par une blague. Je me rends compte que ce n’est pas la seule fois que je publie des blagues à propos de l’idée du sexe en tant que travail.

Un colonel de l’armée s’apprête à commencer le briefing du matin pour son état-major. En attendant que le café soit prêt, le colonel révèle qu’il n’a pas beaucoup dormi la nuit précédente parce que sa femme avait été d’humeur coquine. Il lance la question à son auditoire : quelle part du sexe est «du travail» et quelle part est «du plaisir»? Un major opte pour une proportion de 75-25% en faveur du travail. Un capitaine avance 50-50%. Un lieutenant répond 25-75% en faveur du plaisir, dépendamment du nombre de verres qu’il a bu. Devant l’absence de consensus, le colonel se tourne vers le simple soldat chargé de préparer le café. Qu’est-ce qu’il en pense? Sans hésitation, le jeune soldat répond: «Mon colonel, il faut que ce soit 100% de plaisir.» Surpris, le colonel lui demande pourquoi. «Eh bien, mon colonel, s’il y avait là du travail, les officiers me demanderaient de le faire à leur place».

Peut-être est-ce parce qu’il est le plus jeune, le soldat ne considère que le plaisir que le sexe représente, alors que les hommes plus âgés savent qu’il s’y passe bien davantage. Ceux-ci ont peut-être mieux saisi le fait que le sexe est le travail qui met en marche la machine de reproduction humaine. La biologie et les écrits médicaux présentent les faits mécaniques sans aucune mention d’éventuelles expériences ni de sentiments indescriptibles (le plaisir, en d’autres termes), car on y réduit le sexe à des spermatozoïdes qui se tortillent et se frayent un chemin vers des ovules en attente. Le fossé est vaste entre les faits bruts et les sentiments et sensations impliqués.

Les officiers ont aussi probablement à l’esprit le travail qu’implique l’entretien d’un mariage, en dehors des questions du désir et de la satisfaction. Ils seraient susceptibles de dire que les relations sexuelles sont spéciales (voire sacrée) entre personnes amoureuses, mais ils savent aussi que le sexe fait partie du partenariat visant à traverser la vie ensemble et qu’il faut également le considérer de manière pragmatique. Même les gens qui s’aiment n’ont pas des besoins physiques et émotionnels identiques, ce qui fait que le sexe prend des formes et des significations plus ou moins différentes selon les occasions.

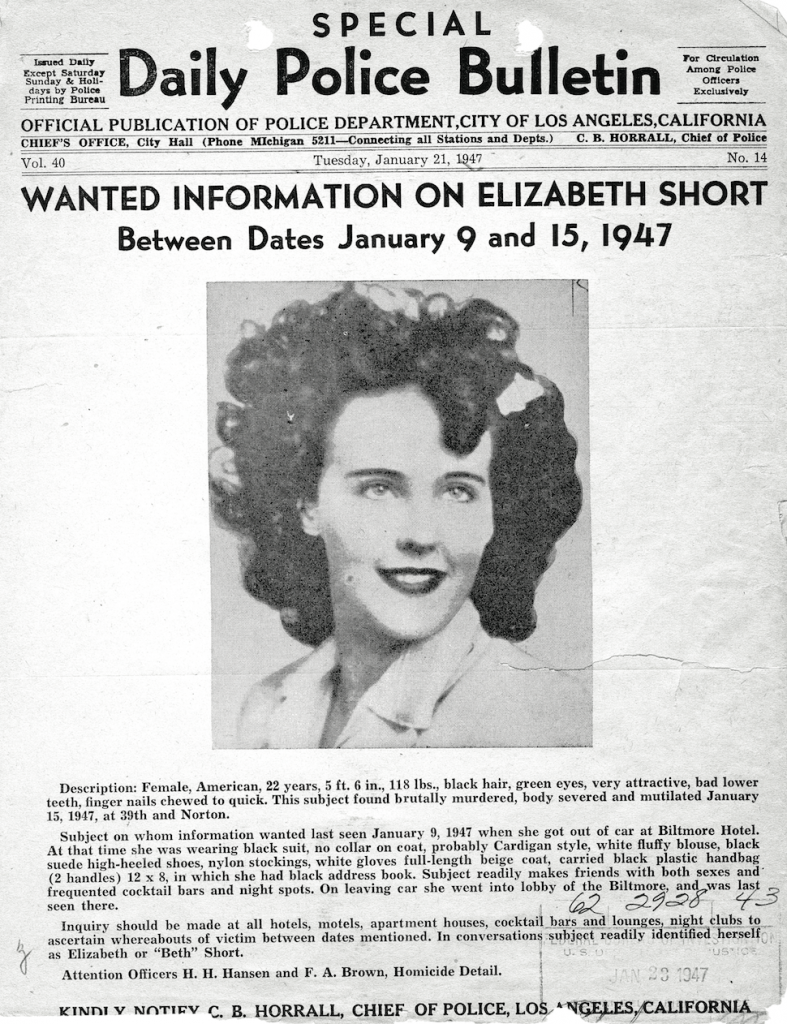

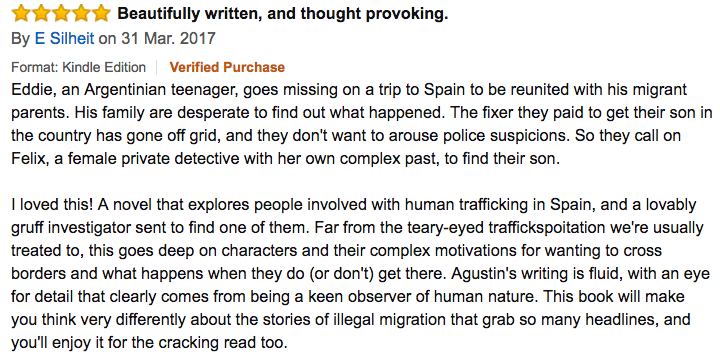

Cette petite histoire met en lumière quelques unes des façons dont le sexe peut être considéré comme un travail. De nos jours, lorsque nous parlons de travail du sexe, le focus est immédiatement mis sur les échanges commerciaux, mais dans le présent article, je vais au-delà de cela et je questionne notre capacité à distinguer clairement quand le sexe implique du travail (entre autres choses) et le travail du sexe (qui implique toutes sortes de choses). Le tollé moral entourant la prostitution et les autres formes de commerce du sexe fait généralement valoir que la différence est évidente entre le sexe bon ou vertueux et le sexe mauvais ou néfaste. Les efforts déployés pour réprimer, condamner, punir et sauver les femmes qui vendent du sexe s’appuient sur l’idée selon laquelle ces dernières occupent une place en marge de la norme et de la communauté, qu’elles peuvent être clairement identifiées et prises en charge par des gens qui savent mieux qu’elles comment elles doivent vivre. Démontrer la fausseté de cette idée discrédite ce projet néocolonial.

Aimer, avec et sans sexe

Nous vivons à une époque où les relations basées sur l’amour romantique et sexuel occupent le sommet de la hiérarchie des valeurs affectives, dans laquelle on suppose que l’amour romantique est la meilleure expérience possible et que le sexe des personnes en amour est le meilleur sexe et ce, à plus d’un titre. La passion romantique est considérée comme significative, une façon pour deux personnes de «ne faire plus qu’une», une expérience qu’on croit parfois amplifiée lors de la conception d’un enfant. D’autres traditions sexuelles s’efforcent également de transcender la banalité dans le sexe (mécanique, frictionnel), par exemple le tantra, qui distingue trois différents objectifs du sexe: la procréation, le plaisir et la libération, le dernier culminant à la perte du sens de soi dans la conscience cosmique. Dans la tradition romantique occidentale, la passion consiste à focaliser une forte émotion positive qui va au-delà du physique, en opposition à la luxure qui n’est que physique, envers une personne particulière. Continue reading

Christmas in the Brothel

Christmas in the Brothel

Since last spring I’ve been providing Naked Anthropologist News to

Since last spring I’ve been providing Naked Anthropologist News to  In Nigeria

In Nigeria About the photos: ‘

About the photos: ‘

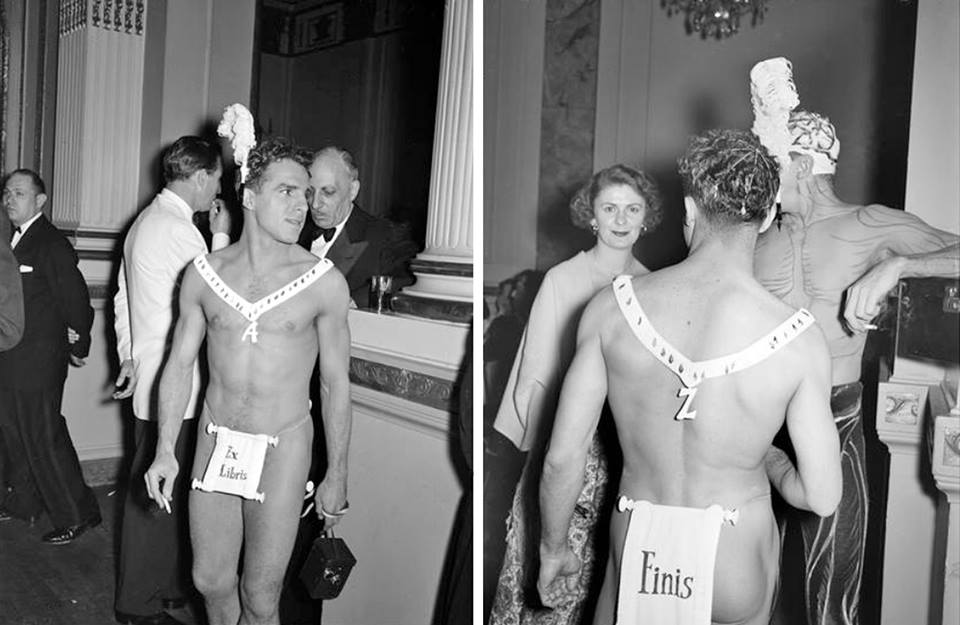

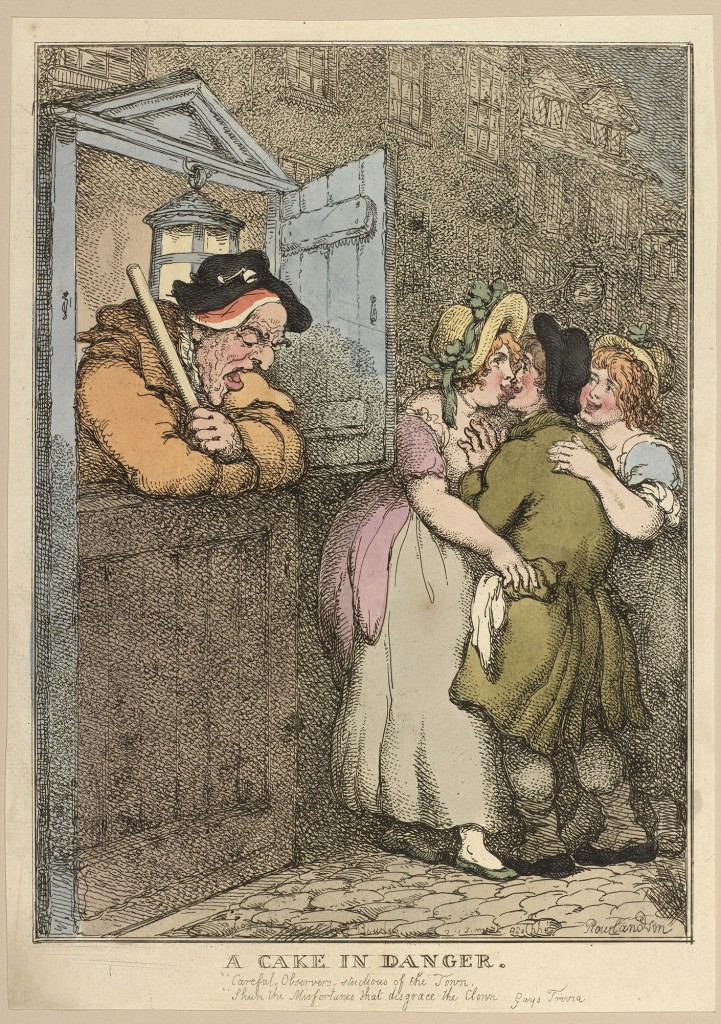

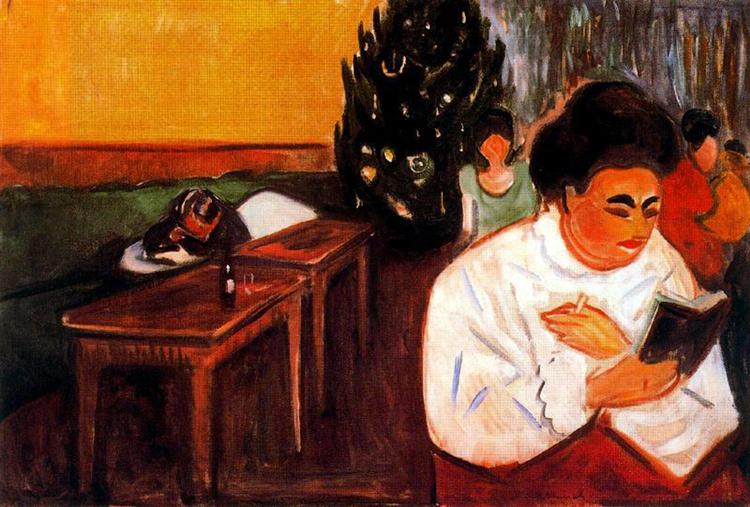

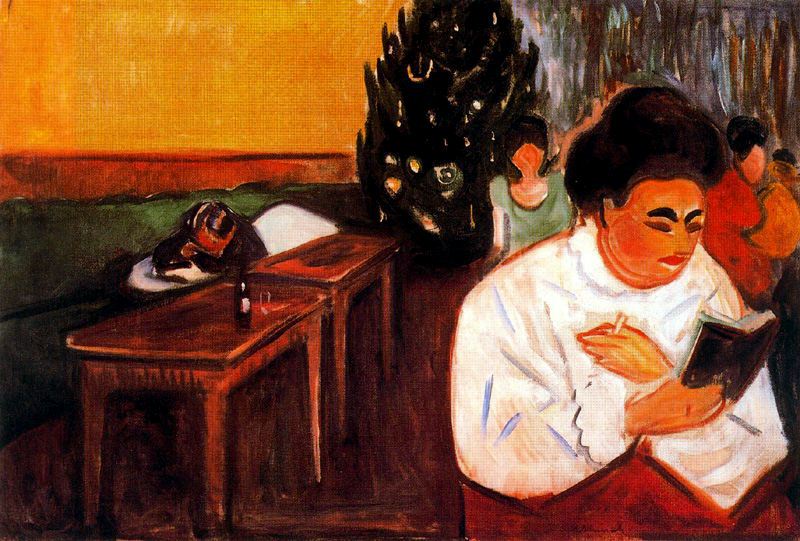

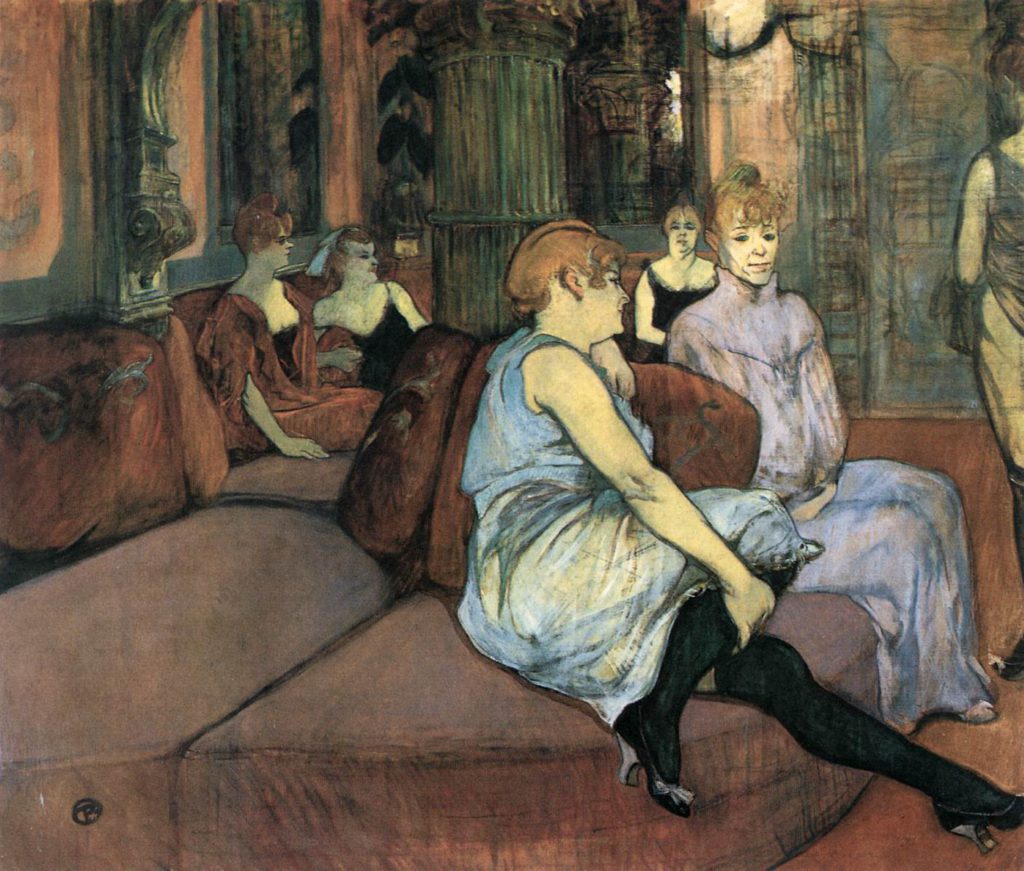

When so-labeled Expresionist Munch painted the scene there was already a body of Impressionist works depicting prostitutes lounging and sitting with expressionless faces as they wait for clients. Toulouse-Lautrec painted this one of many in 1894.

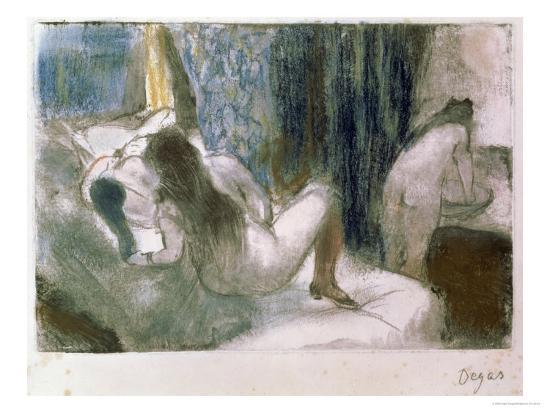

When so-labeled Expresionist Munch painted the scene there was already a body of Impressionist works depicting prostitutes lounging and sitting with expressionless faces as they wait for clients. Toulouse-Lautrec painted this one of many in 1894. The women are sometimes naked, but the tone is unexcited, the poses often awkward. Degas made this painting in 1879, the low-key colour-scheme contributing to an absence of titillation.

The women are sometimes naked, but the tone is unexcited, the poses often awkward. Degas made this painting in 1879, the low-key colour-scheme contributing to an absence of titillation.