As part of the Totally Thames Festival to be held in September 2023 I’m offering a walk I created, Scratching out a living by the river: The Medieval female proletariat, on the 10th and the 20th. This guided walk reflects years of work searching for histories of women who weren’t nobles or royals or kings’ mistresses in the Middle Ages. I’m interested in the medieval female proletariat, as was obvious in my previous walk on the Witches of Manningtree.

As part of the Totally Thames Festival to be held in September 2023 I’m offering a walk I created, Scratching out a living by the river: The Medieval female proletariat, on the 10th and the 20th. This guided walk reflects years of work searching for histories of women who weren’t nobles or royals or kings’ mistresses in the Middle Ages. I’m interested in the medieval female proletariat, as was obvious in my previous walk on the Witches of Manningtree.

In the near-total absence of mention of ordinary (non-wealthy) women in all kinds of histories, and after reading long and hard about everything else about the period, I created six characters who were in search of an author: Me. You’ll meet them on this tour: scullery maid, alewife, washerwoman, brothel worker, huckster, vitteller. A huckster was a woman selling goods in the street, and a vitteller (victualler) was a foodmonger, selling in various settings (think of the word ‘vittels’ in old Western movies). Since few poor women could subsist on the takings from only one job, others besides the brothel-worker sold sex in the streets or in unlicensed bawdy houses. The map at the top, Norden’s from 1593, captures well the area of the river near London Bridge.

The British Library, Add. 42130 f.163v Detail from the Luttrell Psalter, 1325-35, showing women milking sheep and carrying things on their heads.

During several long lockdowns in London, the British Library instated a booking system and procedures for using the Reading Rooms that made working there sometimes infuriating – but also somehow more satisfying than usual. At a certain point I knew there’d be no mentions of individual poorer women anywhere I looked and decided to examine illuminated manuscripts. For a brief period scribes and illustrators (most not monks), mostly in East Anglia, decorated the margins of English manuscripts of religious texts with drawings of people: sometimes peasants, often hybrid monsters and sometimes recognisable women. Working in the Manuscript Room was a revelation, and I did learn how women were looked at – mostly in ways we call misogynistic. Women were considered lustful, untrustworthy and inferior, the sources of men’s problems. Hey ho, I’m an anthropologist and can cope.

The question was How do we know what women were doing if no man recorded it? Before the coming of the printing-press, scribes kept track of certain kinds of accounts and activities, and some monks wrote diaries. But no one described in words what poor women were doing: They belonged to the lowest order of society, close to beasts, and their activities were clearly not thought worth describing: someone had to scrub the floors and empty the chamberpots, that’s all.

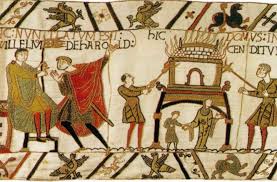

Gender-discrimination is key. Take the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry, which is 70 metres long, depicting 626 human figures, 190 horses, 35 dogs and 3 women. Three in a long story taking place in multiple houses, castles, ships and towns in the build-up to the Battle of Hastings. Does anyone think women weren’t there, leaving battles out of it for the moment? One of the three was a queen, one is considered a mysterious figure and the third is a sort of Everywoman, seen fleeing from the burning of her village (holding a child’s hand, above). The number increases to four if you include a naked female in a sex-scene in the margin. Women were disappeared from history simply by not including pictures of them.

Gender-discrimination is key. Take the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry, which is 70 metres long, depicting 626 human figures, 190 horses, 35 dogs and 3 women. Three in a long story taking place in multiple houses, castles, ships and towns in the build-up to the Battle of Hastings. Does anyone think women weren’t there, leaving battles out of it for the moment? One of the three was a queen, one is considered a mysterious figure and the third is a sort of Everywoman, seen fleeing from the burning of her village (holding a child’s hand, above). The number increases to four if you include a naked female in a sex-scene in the margin. Women were disappeared from history simply by not including pictures of them.

The British Library, Women spinning and carding wool, Detail from the Luttrell Psalter, 1325-35, Add. 42130.

Another kind of disappearance can be seen in guilds like the Worshipful Company of Clothworkers, who formed in the 16th century by amalgamating earlier companies of weavers, fullers and shearmen. But when the clothworkers defined themselves they began at a point in the production of cloth after all tasks conventionally allotted to women were finished: carding, combing and spinning the wool that were necessary before weaving and producing something called cloth. Entrepreneurial men called clothiers organised the distribution and collection of wool carded, combed and spun in women’s homes, and then when guilds were forming they simply left out all that processing. Spinning on the Great Wheel takes great skill, so it couldn’t be claimed that those early processes were somehow too easy to include. One woman historian charmed me by concluding, after long study of spinning all over the British Isles, that men weren’t able to do it.

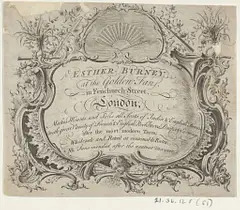

And of course disappearance of women was also juridical, as when women married and ceased to appear in records. Many women ran businesses of their own in the City of London around Cheapside, a centre of London shopping: we know this because of the trade cards they had printed to advertise, such as this one for Esther Burney. But if they married their names disappeared from the record, their businesses now legally belonging to their husbands. The women were most probably still running them but they suffered a civil death (known as coverture).

And of course disappearance of women was also juridical, as when women married and ceased to appear in records. Many women ran businesses of their own in the City of London around Cheapside, a centre of London shopping: we know this because of the trade cards they had printed to advertise, such as this one for Esther Burney. But if they married their names disappeared from the record, their businesses now legally belonging to their husbands. The women were most probably still running them but they suffered a civil death (known as coverture).

The question is what you think history is: The formal activities of royalty and nobility, a tiny proportion of the whole population? The activities of men, particularly the wealthy? Anything related to national government policy and the politicians who made it? For me such histories are simply inadequate.

The particular project reflected in my Southwark walk concerned the river. Some years ago I did a training run by the Thames Discovery Programme to join the Foreshore Recording and Observation Group (FROG – the foreshore being the area along the Thames covered and uncovered by twice-a-day tides). At one point a document was written giving a history of human activities alongside and on the river. There was no single mention of women or female activities anywhere, and I decided That’s it, I’m doing something about this. So I set out to research and as described above found almost nothing there.

The particular project reflected in my Southwark walk concerned the river. Some years ago I did a training run by the Thames Discovery Programme to join the Foreshore Recording and Observation Group (FROG – the foreshore being the area along the Thames covered and uncovered by twice-a-day tides). At one point a document was written giving a history of human activities alongside and on the river. There was no single mention of women or female activities anywhere, and I decided That’s it, I’m doing something about this. So I set out to research and as described above found almost nothing there.

So: How do we know what women were and weren’t doing on the river if they are never mentioned in histories? We can’t conclude they stayed at home taking care of children all the time if they were poor. We can’t even conclude they had a home, though obviously they ate and slept somewhere. We can’t know they didn’t participate in the many occupations recorded for men, because there’s no evidence of their being forbidden. Occupation-names often included -man, but that doesn’t mean the person involved was male.

If what is called data is required, then the first that informs us about poorer women’s work in London may be the Poll Tax Return of 1381 for Southwark, now a borough of the city lying at the southern end of London Bridge. For centuries Southwark’s population lived mainly along the riverside, so this area is a good place to begin to create history about what women were doing. The occupations of my characters were all common and known, though most of them probably didn’t pay well enough income to make them liable for paying poll tax.

All the women relied on water-sources (the river, tidal marshes and springs) to do their work. I have tried to bring them to life in talks I’ve given, and now on a walk where we can stand where they would have stood. Tiny remnants of the 14th century do remain if you use your imagination, like with this image by Uy Hoang from Google streetview that shows the foreshore at the end of Stew Lane on the north bank of the river. This is where the guided walk ends, where wherries picked up clients bound for the brothels and rowed them to the south bank. Whether you call them sex workers, prostitutes or whores, they belonged to the medieval female proletariat.

To follow the story of how I am researching women-and-other-oddballs’ histories to make guided walks, please subscribe to this blog at the top of the right-hand column.

Or follow me on Eventbrite to know when new walks are out.

–Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist

There’s a book on human prehistory which tackles the same theme you are pursuing, which addresses how women are absent from that era, called the Invisible Sex, by Olga Soffer, JM Adovasio, and Jake Page. They point out that the sparse archeological record is mainly filled with artifacts that have not perished, such as stone, and so they concern themselves with perishable artifacts that would have been made such as nets and other forms of weaving.

Others have certainly seen the same thing, I make no claim to originality. What I’ve done after feeling exasperated is create 6 women who lived in the area I’m considering. They reflect all the knowledge there is about how they would have lived but academic standards would point to lack of ‘evidence’. I think we can bring people unnamed in history to life.

Long pre-dating the Medieval, Boudicca is one of our most famous historical figures yet there is no information about the ordinary women of the Iceni or Trinovantes tribes and whether any of them participated in the sacking of Colchester.

Oh and long pre-dating Boudicca, too, but then sources are scarce going that far back because writing things down wasn’t common. About Boudicca we only have the words of Publius Cornelius Tacitus and Cassius Dio, and they don’t say the same things about her. I’m sure women participated in the sacking of Colchester, aren’t you? Just because there’s no reason to think they’d have stayed at home, no evidence women were excluded from politics or activism or war. We are dogged by recent Victorian ideas about women and ‘home’, but there’s no reason to apply them to all earlier times or pre-history.

I’m not personally dogged by Victorian ideas about women, I just don’t know how Celtic British society was organised other than maybe being clan-based? The Roman Legions are always portrayed as being exclusively male.

The Celts didn’t leave written records so information comes from Roman commentators, who weren’t interested in non-noble women. Archaeology provides clues but not facts.