PUBLIC NOTICE: I’ve become a qualified tour guide. Not because I want to take tourists to see the changing of the guard or other typical tourist delights but because I’ve been an inveterate walker all my life and I like talking about pieces of the past other folks might not know about – while walking. You can see me doing it in this photo from my first paid walk, and you can read more about it on the page called London Walks. My fists are out because I was demonstrating a method for ‘swimming’ women accused of witchcraft.

PUBLIC NOTICE: I’ve become a qualified tour guide. Not because I want to take tourists to see the changing of the guard or other typical tourist delights but because I’ve been an inveterate walker all my life and I like talking about pieces of the past other folks might not know about – while walking. You can see me doing it in this photo from my first paid walk, and you can read more about it on the page called London Walks. My fists are out because I was demonstrating a method for ‘swimming’ women accused of witchcraft.

This walk was led along with Rob Smith, a longtime guide and friend. In the past year we have become enamoured with estuaries in the county of Essex – sprawling tidal rivers that end at the North Sea. The landscape can be spectacularly bleak when the tide is out and all is mud.

This walk was led along with Rob Smith, a longtime guide and friend. In the past year we have become enamoured with estuaries in the county of Essex – sprawling tidal rivers that end at the North Sea. The landscape can be spectacularly bleak when the tide is out and all is mud.

The co-leading project started last year when we were walking in Manningtree and Mistley, two small towns on the south bank of the River Stour. Various signs portrayed a man named Matthew Hopkins, who had a brief but nasty career identifying witches in East Anglia in the 17th century. You may remember him as the villain played by Vincent Price in the 1968 horror film Witchfinder-General. Price was nearly 60 when he played the actually only 24-year-old Hopkins, but Never mind, villains who cruelly misuse innocent women are a classic trope, and good fun was had by all watching the movie.

What happened was Rob began making comments about Hopkins and witches, and I kept saying Er, not really, it was more like this or that, and suchlike. Because in my decades of studying the victimising of women I must have thought as much about witches as about prostitutes. The walk proceeded to other things, but towards the end Hopkins reappeared as one-time landlord of a pub with a misleading plaque about him on the wall. I objected, and we discussed it some more, and eventually Rob suggested we do a walk on it.

My stops, as they’re called in the trade, addressed the witch craze. But instead of centring Hopkins I focused on three women accused of witchcraft: Anne and Rebecca West of Lawford and Elizabeth Clarke of Manningtree. We know a few facts about these women because they were accused, charged and tried, and two of them were hanged.

The backdrop to this witch craze was the English Civil War, which for the Parliamentary side (Roundheads) was a moral crusade. For them the Reformation had not gone far enough; war was required to establish true religion and halt the roman catholic back-sliding of Charles I.

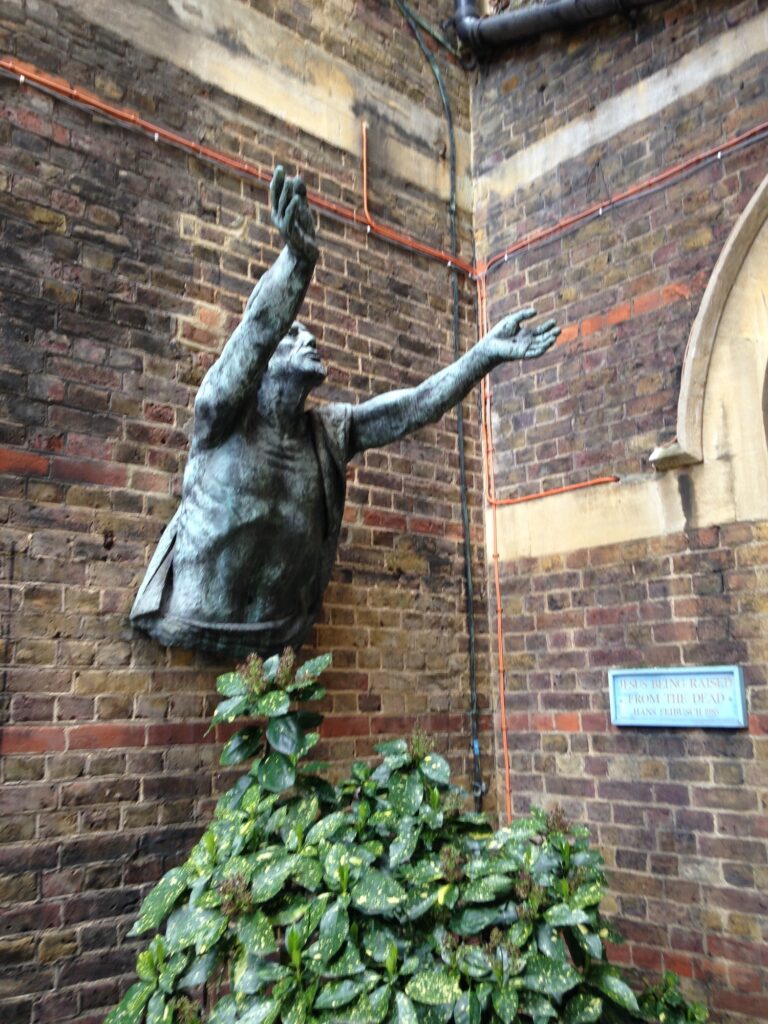

The two-guide walk began on a recent Saturday in the village of Lawford, whose church bears the scars of iconoclasm: sculpture with heads smashed in by Roundhead troops or locals offended by objects associated with old bad ways (click on the picture to see the smashes).

The two-guide walk began on a recent Saturday in the village of Lawford, whose church bears the scars of iconoclasm: sculpture with heads smashed in by Roundhead troops or locals offended by objects associated with old bad ways (click on the picture to see the smashes).

By the mid-17th century numerous Protestant groups had disassociated themselves from the established church of England; they are often grouped together as Dissenters or Non-conformists. But there was one group more passionately attached to this war than others: the Puritans. In East Anglia and Essex, Puritans were numerous and powerful. Their goal was to purify England’s religion; it was a struggle against the anti-Christ that entailed finding and rooting out those in league with the devil.

In the atmosphere of insecurity and mistrust that reigns in civil-war societies, paranoia about the neighbours easily comes to seem normal. This is the context in which a wave of witchcraft accusations swept through the Manningtree area. Witchcraft had always been considered a fact of life: that some people have the ability to damage others by wishing them evil. Demonology was a popular topic; James I had written one of his own.

Many able and intelligent men had left their villages to fight in the war. Women left behind were viewed according to marital status: Wives enjoyed the legal protection of their husbands; widows had rights. But singlewomen, the term used for the never-married, were thought to be morally weak, uncontrolled and unreliable, making them quite vulnerable to exploitation.

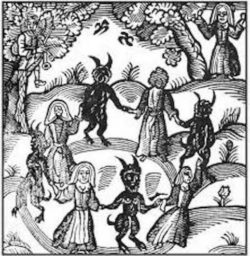

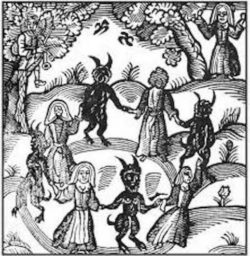

There is also a sexual component: Puritans wanted to suppress activities previously seen as acceptable, like theatre, dancing and sex outside marriage. They saw these behaviours as evidence of ‘witches’ sabbaths’: carousing and sex with the devil. Young women like Rebecca were easily viewed as dangerously lustful.

There is also a sexual component: Puritans wanted to suppress activities previously seen as acceptable, like theatre, dancing and sex outside marriage. They saw these behaviours as evidence of ‘witches’ sabbaths’: carousing and sex with the devil. Young women like Rebecca were easily viewed as dangerously lustful.

The witch-finding described here took place between 1644 and 1647 within a legal framework. Three acts had been passed in the previous century: in 1542, 1562 and 1604. But for the law to proceed against anyone, someone had to make an accusation against them, citing a specific harm done.

Anne and Rebecca West had a history of tiffs with their close neighbours, the Harts, and now Prudence Hart said she suffered a painful miscarriage and paralysis at the hands of Rebecca. Thomas Hart said their son had died crying Rebecca’s name, and Anne was accused of causing a boy’s death some years earlier.

In Manningtree, just to the east of Lawford, a man named John Rivet accused 80-yr-old Elizabeth Clarke of bewitching his wife. Elizabeth said she was a witch and knew other witches, but she wouldn’t name them. Remember that the word witch could connote good powers as well as bad, and a woman who knew herbs and felt spiritual, clairvoyant or intuitive did not have to be ashamed of it. Some folks were called white witches, good witches, blessers, wizards, sorcerers and cunning or wise folk. But the news of Clarke’s confession was taken to a local landowner, John Stearne, who took it to magistrates. They gave him permission to investigate Clarke. Matthew Hopkins, son of a Suffolk minister, had moved to Manningtree and volunteered to help Stearne. Both men had read the many treatises against witchcraft and believed in the evil.

In her confession Clarke implicated other women including Anne and Rebecca West. All three women were accused of entertaining demons in the shape of small animals called familiars, or imps. Cats, dogs, rabbits, frogs, ferrets, owls appear in pictures of the time. Stearne and Hopkins watched Clarke for three nights and said they saw her familiars. Under the 1604 Act Against Witchcraft, the keeping of familiars was punishable by death.

In her confession Clarke implicated other women including Anne and Rebecca West. All three women were accused of entertaining demons in the shape of small animals called familiars, or imps. Cats, dogs, rabbits, frogs, ferrets, owls appear in pictures of the time. Stearne and Hopkins watched Clarke for three nights and said they saw her familiars. Under the 1604 Act Against Witchcraft, the keeping of familiars was punishable by death.

Investigations consisted largely in interrogating women to get them to confess to pacts with the devil. They were walked up and down night after night to prevent their sleeping. Respected women of the town were given the job of searching the accuseds’ bodies looking for ‘devil’s marks’ or ‘teats’ their familiars were thought to suck blood from. The marks were searched for and found between women’s legs, using a metal pricking device. The test was said to be that if women didn’t scream in pain when pricked on a teat then they must be witches. But the tool was spring-loaded so the pricker could be retracted into the handle, meaning women didn’t scream – which constituted evidence of being a witch. [This device is on display in Colchester Castle.]

Investigations consisted largely in interrogating women to get them to confess to pacts with the devil. They were walked up and down night after night to prevent their sleeping. Respected women of the town were given the job of searching the accuseds’ bodies looking for ‘devil’s marks’ or ‘teats’ their familiars were thought to suck blood from. The marks were searched for and found between women’s legs, using a metal pricking device. The test was said to be that if women didn’t scream in pain when pricked on a teat then they must be witches. But the tool was spring-loaded so the pricker could be retracted into the handle, meaning women didn’t scream – which constituted evidence of being a witch. [This device is on display in Colchester Castle.]

A number of local women became expert searchers. Mary Phillips was a Manningtree midwife who accompanied Hopkins and Stearne when they began travelling. The focus on marks was a hallmark of English trials.

Accused women were also tested by ‘swimming’ in a pond, tied crossways (opposite thumbs to big toes) and held by a rope under their armpits so they could be dragged in and out of the water. Since it was believed the pure element of water would reject evil, floating was believed to be a sign of guilt. But the men wielding the rope would have had good control over this test, and it is this specific practice that provoked most opposition to the witch-finders. Parliament eventually forbade the use of swimming in these investigations.

Accused women were also tested by ‘swimming’ in a pond, tied crossways (opposite thumbs to big toes) and held by a rope under their armpits so they could be dragged in and out of the water. Since it was believed the pure element of water would reject evil, floating was believed to be a sign of guilt. But the men wielding the rope would have had good control over this test, and it is this specific practice that provoked most opposition to the witch-finders. Parliament eventually forbade the use of swimming in these investigations.

Hopkins called himself Witchfinder-General and had local support, but he had no mandate from parliament. It’s useful to remember that at this period there was no institution of police, so individuals’ taking it upon themselves to catch criminals was normal. In the legal framework, however, neither he nor Stearne could decide to investigate on their own initiative: there had to be an accusation from an ordinary citizen. What the two men did is awful, but neither of them has struck me as particularly fiendish or even interesting. By offering to investigate they gained power and status and some money, but the amounts weren’t enough to make them rich.

Word of the investigations spread, and Hopkins and Stearne were invited to other towns: to so many places over a short period that it merits being called a witch craze, the term usually used about the phenomenon in European countries. Amounts are recorded in the towns of Aldeburgh and Stowmarket in Suffolk and Kings Lynn in Norfolk that were paid to the men to clear the towns of witches.

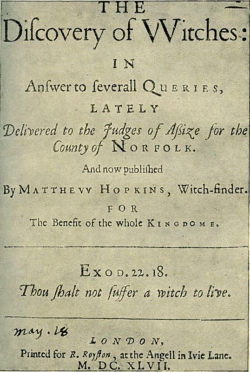

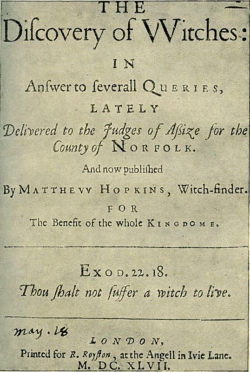

There were doubters, and in some East Anglian places opposition nipped witch-finding in the bud. For this to happen there had to be male authority-figures present who dared to scoff. A minister named John Gaule of Great Staughton in Huntingdonshire objected that parishioners were talking more about witch trials than about God and made it clear that witchfinders were not welcome. Hopkins was questioned at the Norfolk Assizes about his methods and about how was it that he was able to detect witches: was he something special? This led to his publishing a defence, The Discovery of Witches, where he answered criticisms point by point. The bible was quoted: Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live. (Exodus 22:18).

There were doubters, and in some East Anglian places opposition nipped witch-finding in the bud. For this to happen there had to be male authority-figures present who dared to scoff. A minister named John Gaule of Great Staughton in Huntingdonshire objected that parishioners were talking more about witch trials than about God and made it clear that witchfinders were not welcome. Hopkins was questioned at the Norfolk Assizes about his methods and about how was it that he was able to detect witches: was he something special? This led to his publishing a defence, The Discovery of Witches, where he answered criticisms point by point. The bible was quoted: Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live. (Exodus 22:18).

But his chief defence was that he and Stearne only went where they were invited. Even in Manningtree Hopkins and Stearne couldn’t have succeeded without support: at least 100 witnesses testified against accused women. Eventually 36 women from the Manningtree area (the Tendring Hundred) were arrested on charges of witchcraft and imprisoned in ghastly conditions in Colchester Castle. Four died of plague. Hopkins travelled there to get Rebecca West to tell him about witches’ sabbaths attended by the group: This would be proof they were in league with each other. Rebecca gave him what he wanted.

The women were taken to Chelmsford Assizes to be tried. Elizabeth Clarke and 31 others were convicted and hanged there. Four of the convicted were brought to the village green in Manningtree and hanged: Anne West was one of them. Rebecca was spared, having testified against her mother. Did Anne advise Rebecca to save herself? Did Hopkins offer her a deal?

To me the fundamental question is how could it become common and acceptable to accuse your neighbours of witchcraft knowing death was the penalty? The county of Essex accounted for 59% of witchcraft prosecutions, and another large per cent occurred nearby. During the Hopkins-Stearne trials some 250 witches were accused and at least 100 were hanged.

Hopkins’s death at age 26 in August 1647 is recorded in the Mistley parish register; Stearne said he died of consumption. He was buried in a churchyard now decrepit, and his ghost is said to haunt a nearby pond. In the face of growing opposition Stearne found he had other things to do, though he also published a treaty on witchfinding. He then retired, and the craze fizzled out.

Hopkins’s death at age 26 in August 1647 is recorded in the Mistley parish register; Stearne said he died of consumption. He was buried in a churchyard now decrepit, and his ghost is said to haunt a nearby pond. In the face of growing opposition Stearne found he had other things to do, though he also published a treaty on witchfinding. He then retired, and the craze fizzled out.

Novels written by historians can often illuminate sketchy history, bringing unknown persons from the past to life. I can recommend A. K. Blakemore’s novel The Manningtree Witches, in which Rebecca is the principal character. After the hangings she leaves town and travels to London, surely a likely outcome after what she’d been through. Blakemore then has her getting a ship to the New World. Since the destination could well have been Massachusetts, already settled by many Essex Puritans, word of who she was would follow her, making this quite a charged proposition. She could easily have become a prostitute, though.

What I’ve recounted here took place on a walk through rolling countryside on the eastern edge of Dedham Vale (Constable country), on paths Rebecca and Anne would have trodden, then along the River Stour at high tide with a classic beach-scene in progress, and on streets where 16th- and 17th-century houses are masked by Georgian facades. Rob talked about other periods, including Richard Rigby’s failed attempt to make Mistley a spa in the 18th century. We saw Robert Adam-designed towers and late 19th-century factory buildings and pubs where Hopkins and Stearne could have met with locals to gossip. We all stopped for a drink in one that’s next to the green where Anne West was hanged: the darkest moment in the walk, but somehow more meaningful because you are actually there. We stopped at the kind of pond where ‘swimming’ would have been carried out, which you see me describing in the photo at the start.

What I’ve recounted here took place on a walk through rolling countryside on the eastern edge of Dedham Vale (Constable country), on paths Rebecca and Anne would have trodden, then along the River Stour at high tide with a classic beach-scene in progress, and on streets where 16th- and 17th-century houses are masked by Georgian facades. Rob talked about other periods, including Richard Rigby’s failed attempt to make Mistley a spa in the 18th century. We saw Robert Adam-designed towers and late 19th-century factory buildings and pubs where Hopkins and Stearne could have met with locals to gossip. We all stopped for a drink in one that’s next to the green where Anne West was hanged: the darkest moment in the walk, but somehow more meaningful because you are actually there. We stopped at the kind of pond where ‘swimming’ would have been carried out, which you see me describing in the photo at the start.

Many dismiss the events I’ve described as being nowadays unthinkable superstitious hooey. Hangings aside, I can personally think of several similar crazes that have happened in my lifetime that punish innocent-enough individuals, which you can read about in posts on this blog going back to 2008.

Note about sources: I’ve been able to see assize-court records, as well as mass-printed news pamphlets, which is where ordinary people would have become familiar with names, accusations and hangings and seen wood-cuts depicting witches’ activities. Those were the popular media of the time. I read many scholarly works giving statistics and interpreting events in various ways. As for focusing on the accused women, I’m far from the first person to do it. In the course of my research I was given two walking brochures by Alison Rowlands at the University of Essex that centre victims, created by a number of local Essex women. One is called Walking with Witches. Alison also gave me the name of a former student, James Cundick, who made maps of Hopkins and Stearne’s travels, as well of those of William Dowsing, the Iconoclast-General in charge of smashing down popishness in churches. In the screen-capture above, taken from James’s map, you see the area I’ve been talking about. All these sources helped me put together my own ideas. Thank you James and Alison.

Note about sources: I’ve been able to see assize-court records, as well as mass-printed news pamphlets, which is where ordinary people would have become familiar with names, accusations and hangings and seen wood-cuts depicting witches’ activities. Those were the popular media of the time. I read many scholarly works giving statistics and interpreting events in various ways. As for focusing on the accused women, I’m far from the first person to do it. In the course of my research I was given two walking brochures by Alison Rowlands at the University of Essex that centre victims, created by a number of local Essex women. One is called Walking with Witches. Alison also gave me the name of a former student, James Cundick, who made maps of Hopkins and Stearne’s travels, as well of those of William Dowsing, the Iconoclast-General in charge of smashing down popishness in churches. In the screen-capture above, taken from James’s map, you see the area I’ve been talking about. All these sources helped me put together my own ideas. Thank you James and Alison.

I took the photo in Lawford church, Rob took the other photos, and I believe the various woodcuts and early printings are in the public domain. If they’re not, please let me know.

Yes we’ll offer the walk again, and we’re getting another estuary walk ready now. Yes my own walks will be in London; I’m working on those. Subscribe to this blog and you’ll find out. Leave any questions or comments below and I’ll respond.

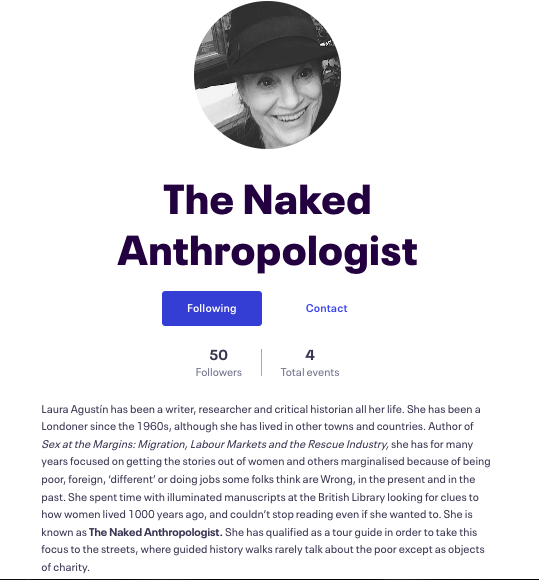

–Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist

Like this:

Like Loading...

To bring some post/decolonial history to a walking-tour literary festival, I’m offering Monica Ali’s Brick Lane. The novel’s protagonist is Nazneen, a Bangladeshi woman who comes to live in an estate in the East End of London via an arranged marriage in the 1980s. Her husband is pompous but not mean, a man who assumes she will be his obedient stay-at-home wife, cooking, providing children and not needing to learn English or even leave the house much. In the course of the 15 years covered by the book Nazneen changes from accepting life as a shut-in to being an autonomous woman. In literary terms it’s a bildungsroman; in feminist terms it could be set anywhere.

To bring some post/decolonial history to a walking-tour literary festival, I’m offering Monica Ali’s Brick Lane. The novel’s protagonist is Nazneen, a Bangladeshi woman who comes to live in an estate in the East End of London via an arranged marriage in the 1980s. Her husband is pompous but not mean, a man who assumes she will be his obedient stay-at-home wife, cooking, providing children and not needing to learn English or even leave the house much. In the course of the 15 years covered by the book Nazneen changes from accepting life as a shut-in to being an autonomous woman. In literary terms it’s a bildungsroman; in feminist terms it could be set anywhere. The walk recounts history of Bengali residents in the Whitechapel area, beginning at the market on Whitechapel Road and winding through backstreets before reaching Brick Lane. A diverse but predominantly Bengali population live in a variety of council housing interspersed with remnants of Victorian streets where Irish and Jewish migrants once held sway and which English reformers worked to improve.

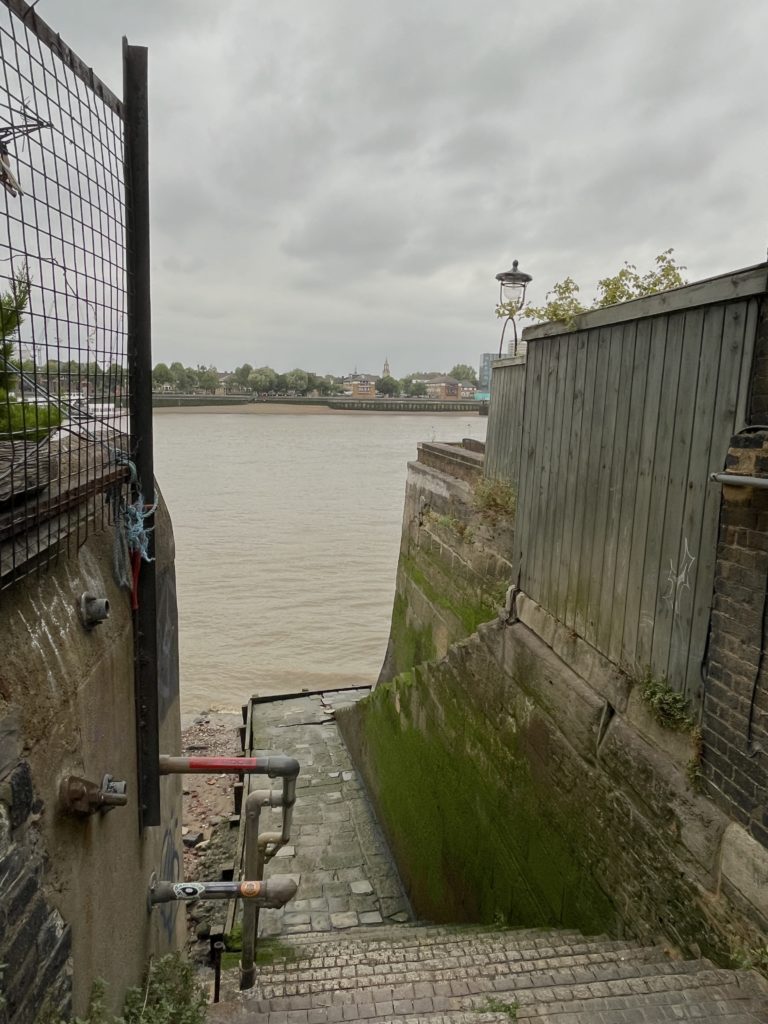

The walk recounts history of Bengali residents in the Whitechapel area, beginning at the market on Whitechapel Road and winding through backstreets before reaching Brick Lane. A diverse but predominantly Bengali population live in a variety of council housing interspersed with remnants of Victorian streets where Irish and Jewish migrants once held sway and which English reformers worked to improve. Bengalis have lived in a wide area of the East End of London for hundreds of years, first arriving as lascar seamen hired by the East India Company when their own sailors deserted. Lascars were treated and paid badly, and once they arrived at the London docks were largely left to their own devices to survive, often without knowing English or owning clothes for cold weather. Then when they wanted to get jobs on voyages back to India they were usually not employed, with the result that many began carving out lives on land, marrying local English women.

Bengalis have lived in a wide area of the East End of London for hundreds of years, first arriving as lascar seamen hired by the East India Company when their own sailors deserted. Lascars were treated and paid badly, and once they arrived at the London docks were largely left to their own devices to survive, often without knowing English or owning clothes for cold weather. Then when they wanted to get jobs on voyages back to India they were usually not employed, with the result that many began carving out lives on land, marrying local English women. The curry houses and sweet shops in Brick Lane have made history, founded by men who would never have cooked at home but who learned to provide for themselves aboard ships and opened small cafes when they found English food unpalatable. While the northern half of Brick Lane no longer feels like Banglatown, the southern half still does.

The curry houses and sweet shops in Brick Lane have made history, founded by men who would never have cooked at home but who learned to provide for themselves aboard ships and opened small cafes when they found English food unpalatable. While the northern half of Brick Lane no longer feels like Banglatown, the southern half still does.

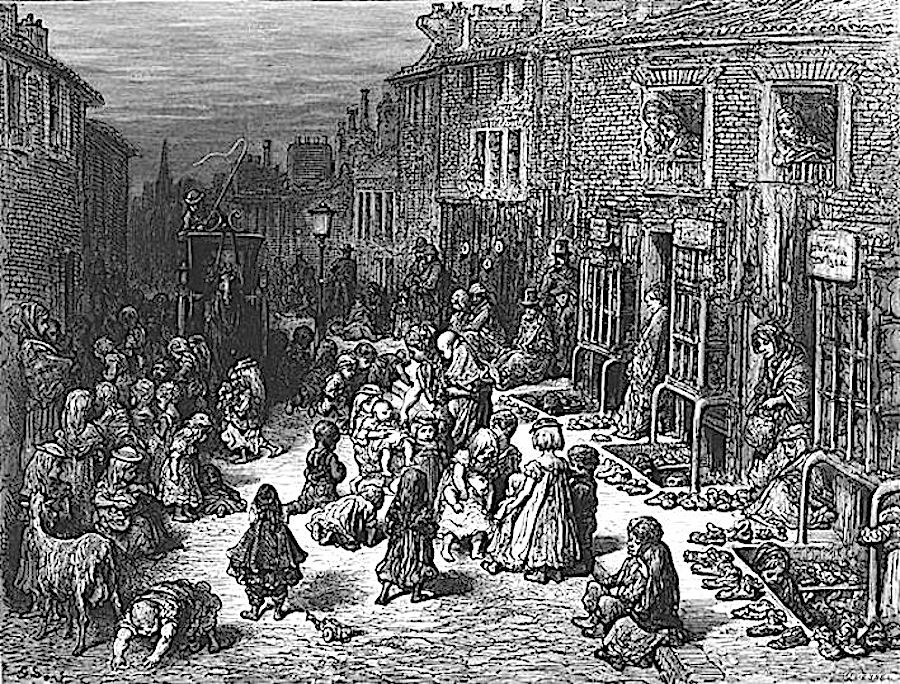

All our lives society has been represented to us as a hierarchy or pyramid in which the rich are located at the top, the middle class sits underneath and workers sprawl at the bottom. Anything lower than the bottom is called underclass, a lot of dysfunctional nobodies. Isn’t it still assumed everyone is striving to move up this ladder? Failure is constructed as happening downwards, a falling into an abyss – the word Jack London and Mary Higgs used to describe how the poor were forced to live.

All our lives society has been represented to us as a hierarchy or pyramid in which the rich are located at the top, the middle class sits underneath and workers sprawl at the bottom. Anything lower than the bottom is called underclass, a lot of dysfunctional nobodies. Isn’t it still assumed everyone is striving to move up this ladder? Failure is constructed as happening downwards, a falling into an abyss – the word Jack London and Mary Higgs used to describe how the poor were forced to live.

The back of the buildings face onto where for several hundred years poorly-paid soldiers, their girlfriends, wives, children and hangers-on scraped together livings. Knightsbridge (the street) was scene of goings-on that wealthy folks called disorderly, meaning drunkenness, carousing, noise, fights, streetwalking, numerous pubs and two major music halls whose raucous style of entertainment suited the working class. Sites of Low Pleasures, according to those set on raising the tone of the area.

The back of the buildings face onto where for several hundred years poorly-paid soldiers, their girlfriends, wives, children and hangers-on scraped together livings. Knightsbridge (the street) was scene of goings-on that wealthy folks called disorderly, meaning drunkenness, carousing, noise, fights, streetwalking, numerous pubs and two major music halls whose raucous style of entertainment suited the working class. Sites of Low Pleasures, according to those set on raising the tone of the area.

The best thing about this award is the fact that someone like myself can qualify at all. The Women’s History Network, recognising those doing rigorous research without being employed academics, have a separate grant category for us. I shared this prize with

The best thing about this award is the fact that someone like myself can qualify at all. The Women’s History Network, recognising those doing rigorous research without being employed academics, have a separate grant category for us. I shared this prize with  So sometime this winter when prices are lower and the weather absolute crap, I’ll go to Norwich for some days and visit the cathedral to see in person this sculpture of a medieval laundress in the act of being robbed by a barefoot boy. She’s

So sometime this winter when prices are lower and the weather absolute crap, I’ll go to Norwich for some days and visit the cathedral to see in person this sculpture of a medieval laundress in the act of being robbed by a barefoot boy. She’s

You can see what walks I have coming up via the tab on the top menu called

You can see what walks I have coming up via the tab on the top menu called

When considering telling a history, whose point of view do you take? In most histories the author presumes to have an objective meta-overview of events and to know what’s important and what’s trivial. In these accounts women are usually subordinates or walk-on characters and the poor and working-class hardly appear unless they are the objects of bourgeois charity. When Antonio Gramsci referred to the subaltern and Southeast Asian scholars built a field of studies on it, they put at the centre people rarely given their due in histories.

When considering telling a history, whose point of view do you take? In most histories the author presumes to have an objective meta-overview of events and to know what’s important and what’s trivial. In these accounts women are usually subordinates or walk-on characters and the poor and working-class hardly appear unless they are the objects of bourgeois charity. When Antonio Gramsci referred to the subaltern and Southeast Asian scholars built a field of studies on it, they put at the centre people rarely given their due in histories.

PUBLIC NOTICE: I’ve become a qualified tour guide. Not because I want to take tourists to see the changing of the guard or other typical tourist delights but because I’ve been an inveterate walker all my life and I like talking about pieces of the past other folks might not know about – while walking. You can see me doing it in this photo from my first paid walk, and you can read more about it on the page called

PUBLIC NOTICE: I’ve become a qualified tour guide. Not because I want to take tourists to see the changing of the guard or other typical tourist delights but because I’ve been an inveterate walker all my life and I like talking about pieces of the past other folks might not know about – while walking. You can see me doing it in this photo from my first paid walk, and you can read more about it on the page called