Last week a Madrid tribunal declared that sex workers can unionise but prostitutes can’t – or that’s what it comes down to. Sindicato OTRAS was granted conventional union status in the summer, having filed the necessary paperwork. But when the news got out, scandalised politicians vowed they wouldn’t allow it, because the current government has declared itself abolitionist. Before long, several women’s organisations in different parts of Spain had put together a lawsuit against the union, on the grounds that prostitution can’t be a job (because it’s violence against women, slavery and so on). I’m simplifying, but believe me, you don’t want to read the convoluted legal language involved.

Last week a Madrid tribunal declared that sex workers can unionise but prostitutes can’t – or that’s what it comes down to. Sindicato OTRAS was granted conventional union status in the summer, having filed the necessary paperwork. But when the news got out, scandalised politicians vowed they wouldn’t allow it, because the current government has declared itself abolitionist. Before long, several women’s organisations in different parts of Spain had put together a lawsuit against the union, on the grounds that prostitution can’t be a job (because it’s violence against women, slavery and so on). I’m simplifying, but believe me, you don’t want to read the convoluted legal language involved.

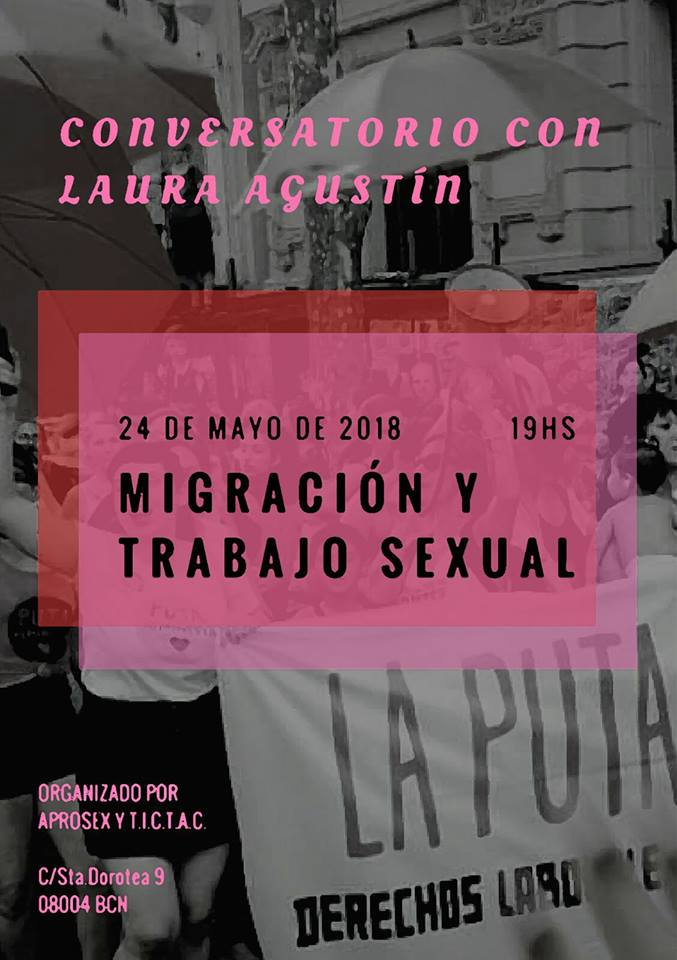

I spent two evenings with members of Aprosex in late May in Barcelona, one of them a conversatorio with me and many enthusiastic participants held at the headquarters of t.i.c.t.a.c. Shortly afterwards, Aprosex filed papers to become a union: Sindicato OTRAS (Organización de Trabajadoras Sexuales). Sex workers who call themselves anything are welcome: cam-girls, phone-sex operators, strippers, porn actors, bar hostesses, escorts, workers in flats. Some of these offer services many consider to be prostitution.

I spent two evenings with members of Aprosex in late May in Barcelona, one of them a conversatorio with me and many enthusiastic participants held at the headquarters of t.i.c.t.a.c. Shortly afterwards, Aprosex filed papers to become a union: Sindicato OTRAS (Organización de Trabajadoras Sexuales). Sex workers who call themselves anything are welcome: cam-girls, phone-sex operators, strippers, porn actors, bar hostesses, escorts, workers in flats. Some of these offer services many consider to be prostitution.

Job-titles don’t say everything. Some who’ve embraced the term sex worker hate the word prostitute, but a lot of others comfortably use it, especially in Romance languages. A recently-formed group call themselves Colectivo de Prostitutas de Sevilla. The whore-word puta is in process of reclamation, appearing on banners as you see above. Some feel okay calling themselves sex workers as long as it’s clear that they aren’t prostitutes. The paperwork for OTRAS referred to sex work in all its forms, which abolitionists immediately interpreted to mean prostitution: the thing they love to hate.

I don’t need to describe the arguments made by the women’s-group plaintiffs; they are well known. I note their horror that prostitutes, who exist because of patriarchy, can argue that a union will combat it. I have written about anti-prostitution ideas many times, last in The New Abolitionist Model.

But the specific Spanish legal context determined how opponents could argue a lawsuit. In the Penal Code prostitution is not defined as illegal, which rights activists complain leads to alegal status that disadvantages sex workers. You may well think that if an activity is not prohibited or defined as wrong in law then it must by default be considered part of ordinary (legal) life. But the ambiguity has been exploited to claim that if prostitution is not defined as legal work by law and listed in a national register of occupations then it can’t be a job. Porn acting and web-camming might be. The term sex worker seems not precise enough to be, and anyway abolitionists read it as a euphemism for prostitute.

However, it’s more complicated than that. Amongst jobs that are listed in the national register is work in clubes de alterne, bar-venues with private spaces in the back or upstairs for workers to take clients for sex. The word alterne, from the verb alternar, refers to socialising and drinking with customers, and chicas de alterne is a common euphemism for women who work in clubes de carretera, hoteles de plaza, casas de citas and puticlubs – all names of public businesses that may get called brothels, but they may also have a lot more going on in them: films, shows, dance-floors, jacuzzis, who knows what else in a place like the one above in Málaga. Businesses you can call brothels also exist in residential buildings. All these are legal. I wrote more about them in The Sex Industry in Spain. In other parts of the world chicas de alterne are known as bar girls or hostesses.

However, it’s more complicated than that. Amongst jobs that are listed in the national register is work in clubes de alterne, bar-venues with private spaces in the back or upstairs for workers to take clients for sex. The word alterne, from the verb alternar, refers to socialising and drinking with customers, and chicas de alterne is a common euphemism for women who work in clubes de carretera, hoteles de plaza, casas de citas and puticlubs – all names of public businesses that may get called brothels, but they may also have a lot more going on in them: films, shows, dance-floors, jacuzzis, who knows what else in a place like the one above in Málaga. Businesses you can call brothels also exist in residential buildings. All these are legal. I wrote more about them in The Sex Industry in Spain. In other parts of the world chicas de alterne are known as bar girls or hostesses.

The Audiencia’s decision noted there would be no problem if chicas de alterne wanted to unionise on the basis of their work socialising. They also do prostitution? No problem. If you find this bizarrely contradictory, consult the Mad Hatter – he understands perfectly. Loopholes like these provide endless paid occupation for lawyers and campaigners like Plataforma 8 de marzo, Comisión para la Investigación de Malos Tratos a Mujeres and L’Escola: women’s organisations who took Sindicato OTRAS to court.

The Audiencia’s decision noted there would be no problem if chicas de alterne wanted to unionise on the basis of their work socialising. They also do prostitution? No problem. If you find this bizarrely contradictory, consult the Mad Hatter – he understands perfectly. Loopholes like these provide endless paid occupation for lawyers and campaigners like Plataforma 8 de marzo, Comisión para la Investigación de Malos Tratos a Mujeres and L’Escola: women’s organisations who took Sindicato OTRAS to court.

In this case they made many familiar claims about prostitution being violence against women and an obstacle to equality, citing Spanish legislation. They leaned heavily on arguments about trafficking and prostitution being inseparable, quoting EU and UN declarations. But they also claimed that prostitution’s not being an occupation inscribed in Spain’s national job register means that those who practise it can’t be workers because their job does not exist.

Further complications relate to the requirement that workers forming unions need to have the status of employees in a setting where employers define and regulate their work. In the case of prostitution, plaintiffs argued, this would mean managers telling prostitutes how to have sex with clients, which they don’t do. To underscore their point claimants expressed outrage at the possibility that bosses and workers might be able to damage the highly personal nature of sex (personalísimo). The way these repressive arguments opportunistically use the principle of sexual freedom frankly makes me sick.

Requiring workers to assume self-employed status is common practice in sex-industry businesses in many countries, allowing bosses to avoid accusations of pimping and also avoid providing decent working conditions. Being self-employed means workers have no right to negotiate terms or problems in what obviously are workplaces. Individuals may complain to bosses, but only trade unions have the ability to negotiate formally with management without being ignored or simply dismissed. Nota bene: Caveats apply. There is no one meaning to the term trade union, and national contexts differ. Freelance/self-employed/autonomous workers are generally excluded, but new unions want to change that.

Requiring workers to assume self-employed status is common practice in sex-industry businesses in many countries, allowing bosses to avoid accusations of pimping and also avoid providing decent working conditions. Being self-employed means workers have no right to negotiate terms or problems in what obviously are workplaces. Individuals may complain to bosses, but only trade unions have the ability to negotiate formally with management without being ignored or simply dismissed. Nota bene: Caveats apply. There is no one meaning to the term trade union, and national contexts differ. Freelance/self-employed/autonomous workers are generally excluded, but new unions want to change that.

OTRAS will appeal to the Supreme Court and meanwhile, despite misleading press headlines, have not been declared illegal. The Audiencia’s decision annulled the group’s statutes (by-laws) but hasn’t the power to dissolve the union (the whole long cryptic decision is at the bottom of the previous link). El Diario did better on the decision than most media outlets.

Everyone wants to know why the association of sex-business owners is allowed to exist. ANELA was inscribed in the national register of associations in 2004, defining their activity as dispensar “productos o servicios” a terceras personas ajenas al establecimiento, “que ejerzan el alterne y la prostitución por cuenta propia”: provide products or services to self-employed third persons… who practise alterne and prostitution.

It is interesting that ANELA’s first attempt to register was also frustrated by the mention of prostitution. Told to remove it because it isn’t legal employment, they refused, citing a 2001 EU court decision that prostitution may be an economic activity for self-employed persons, in the absence of force or coercion. In the same Audiencia (Sala de lo Social) where the case against OTRAS was held, ANELA was initially refused inscription. They appealed to the Supreme Court and won, judges saying that providing the conditions for prostitution to take place doesn’t necessarily make an owner a pimp (proxeneta). Go figure.

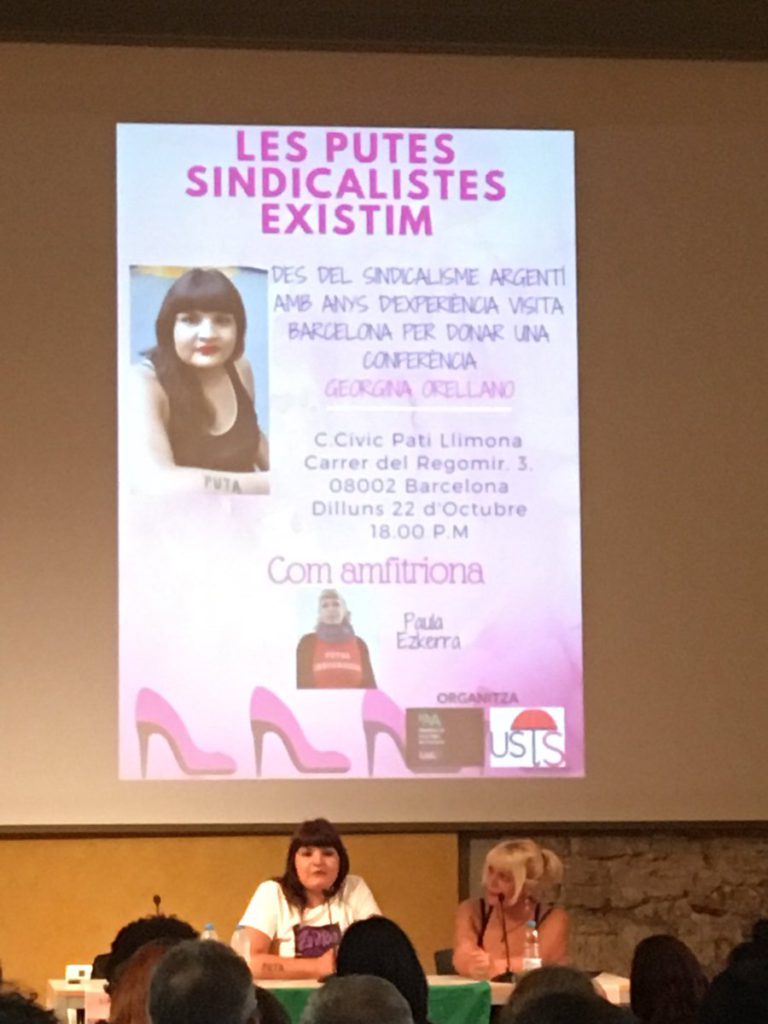

Meanwhile, if you weren’t already dazed by contradictions, another sex workers’ union opened this past summer, also in Barcelona. Unión Sindical de Trabajo Sexual was founded as a branch of the already-existing Intersindical Alternativa de Catalunya, and moral crusaders have no argument with it. Not because of which job-titles the workers claim but because, as a branch, they are not a separate autonomous legal entity. I know – it just doesn’t add up.

Meanwhile, if you weren’t already dazed by contradictions, another sex workers’ union opened this past summer, also in Barcelona. Unión Sindical de Trabajo Sexual was founded as a branch of the already-existing Intersindical Alternativa de Catalunya, and moral crusaders have no argument with it. Not because of which job-titles the workers claim but because, as a branch, they are not a separate autonomous legal entity. I know – it just doesn’t add up.

Enough. I’ve understood for many years that the term prostitution can never be pinned down. It isn’t ‘just a word’: its meaning is far from obvious; its connotations reach deep into patriarchal mechanisms for keeping women down and divided against each other. The comfortable middle-class Spanish feminists desiring to bring down a trade union for sex workers perfectly prove the point. In Prostitution Law and the Death of Whores I went into this in detail.

When I was revising this I saw I hadn’t tagged for Rescue Industry. The hostility of government spokesfolk and organisations that agreed to do their dirty work goes beyond any pretense to be helping and saving. This is about upholding the status quo for a small but influential cadre of privileged women who believe that they Know Best about everything under the sun. Patriarchal hierarchies work for women at the top.

Some things I’ve written about Spain, in English (note Spanish at the bottom):

Some things I’ve written about Spain, in English (note Spanish at the bottom):

A novel, The Three-Headed Dog, is set on the Costa del Sol and Madrid, amongst migrants doing various kinds of sex work. In the sequel the setting moves from Galicia through Málaga to Calais and London.

The Sex Industry in Spain: Sex clubs, flats, agriculture, tourism

Highways as sexwork places, with chairs

Sexwork and migration fiction, part 2: Jobs in the sex industry

Change the world by getting men to stop buying sex: Spain

In Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets and the Rescue Industry, the field work was carried out in Spain.

Lista de publicaciones mias en castellano.

—Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist

Is a sindicato the same as a union always?

Pingback: In the News (#892) | The Honest Courtesan