To bring some post/decolonial history to a walking-tour literary festival, I’m offering Monica Ali’s Brick Lane. The novel’s protagonist is Nazneen, a Bangladeshi woman who comes to live in an estate in the East End of London via an arranged marriage in the 1980s. Her husband is pompous but not mean, a man who assumes she will be his obedient stay-at-home wife, cooking, providing children and not needing to learn English or even leave the house much. In the course of the 15 years covered by the book Nazneen changes from accepting life as a shut-in to being an autonomous woman. In literary terms it’s a bildungsroman; in feminist terms it could be set anywhere.

To bring some post/decolonial history to a walking-tour literary festival, I’m offering Monica Ali’s Brick Lane. The novel’s protagonist is Nazneen, a Bangladeshi woman who comes to live in an estate in the East End of London via an arranged marriage in the 1980s. Her husband is pompous but not mean, a man who assumes she will be his obedient stay-at-home wife, cooking, providing children and not needing to learn English or even leave the house much. In the course of the 15 years covered by the book Nazneen changes from accepting life as a shut-in to being an autonomous woman. In literary terms it’s a bildungsroman; in feminist terms it could be set anywhere.

The walk recounts history of Bengali residents in the Whitechapel area, beginning at the market on Whitechapel Road and winding through backstreets before reaching Brick Lane. A diverse but predominantly Bengali population live in a variety of council housing interspersed with remnants of Victorian streets where Irish and Jewish migrants once held sway and which English reformers worked to improve.

The walk recounts history of Bengali residents in the Whitechapel area, beginning at the market on Whitechapel Road and winding through backstreets before reaching Brick Lane. A diverse but predominantly Bengali population live in a variety of council housing interspersed with remnants of Victorian streets where Irish and Jewish migrants once held sway and which English reformers worked to improve.

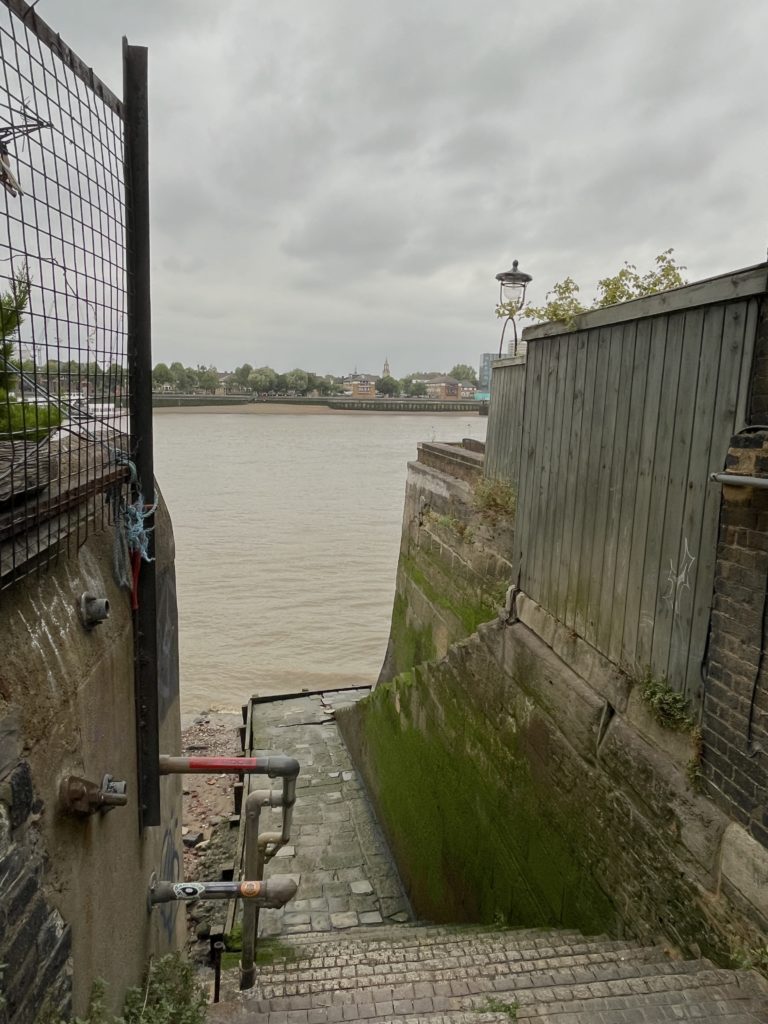

Bengalis have lived in a wide area of the East End of London for hundreds of years, first arriving as lascar seamen hired by the East India Company when their own sailors deserted. Lascars were treated and paid badly, and once they arrived at the London docks were largely left to their own devices to survive, often without knowing English or owning clothes for cold weather. Then when they wanted to get jobs on voyages back to India they were usually not employed, with the result that many began carving out lives on land, marrying local English women.

Bengalis have lived in a wide area of the East End of London for hundreds of years, first arriving as lascar seamen hired by the East India Company when their own sailors deserted. Lascars were treated and paid badly, and once they arrived at the London docks were largely left to their own devices to survive, often without knowing English or owning clothes for cold weather. Then when they wanted to get jobs on voyages back to India they were usually not employed, with the result that many began carving out lives on land, marrying local English women.

This for a long time meant that they formed no discrete ethnic community, becoming part of the large cosmopolitan area of the docks. Modern migrations date from the disassembling of India when the British left, a violent process that pushed many people to new areas. In the 1950s and 60s they were leaving from East Pakistan; after winning a war of independence in 1971 it was Bangladesh. The term Bengali includes the area of West Bengal in India.

The curry houses and sweet shops in Brick Lane have made history, founded by men who would never have cooked at home but who learned to provide for themselves aboard ships and opened small cafes when they found English food unpalatable. While the northern half of Brick Lane no longer feels like Banglatown, the southern half still does.

The curry houses and sweet shops in Brick Lane have made history, founded by men who would never have cooked at home but who learned to provide for themselves aboard ships and opened small cafes when they found English food unpalatable. While the northern half of Brick Lane no longer feels like Banglatown, the southern half still does.

On the walk, alongside local history, you hear excerpts from a novel that caused furore in the area when it was published. The protestors were mostly patriarchs who probably had not read more than a few words of the book. Salman Rushdie crossed swords with Germaine Greer over it. Join Monica Ali’s Brick Lane – Bengali migrants in the East End on Saturday 22 March at 1300.

—Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist