Social work, whether voluntary or paid, rests on an assumption that people with problems can be helped by outsiders who provide services that facilitate solutions. Hands predominate in icons used on social-work websites: holding hands, piles of hands, hands of different shapes and colours. I suppose these are meant to signify working together – mutuality – non-hierarchy – equality. But how many social-work situations involving a sex worker reflect those values? Take this news item from Los Angeles:

Social work, whether voluntary or paid, rests on an assumption that people with problems can be helped by outsiders who provide services that facilitate solutions. Hands predominate in icons used on social-work websites: holding hands, piles of hands, hands of different shapes and colours. I suppose these are meant to signify working together – mutuality – non-hierarchy – equality. But how many social-work situations involving a sex worker reflect those values? Take this news item from Los Angeles:

Getting tough on underage prostitution

Getting tough on underage prostitution

LA County calls on legislators to toughen laws, while those who work with young prostitutes grapple with how to get them off the streets. “Children cannot give consent by definition,” said Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas. McSweeney said there are times when deputies pick up an underage girl and take her to county social services. Often, he said, that girl will end up in a group home, flee the next day, and be back on the street that night. It’s a revolving door, he said, and the system could use some tweaking.

Rejection of help is widely known amongst people who sell sex of all ages, yet to question ideas about helping is frowned upon. It is said people who are at least trying to do good deserve credit. Do they have to be perfect? At any rate, they are not employed as soldiers or bankers, they are socially involved, at least they care. But for most social workers, the job is just a job. They don’t imagine themselves to be saints but do appreciate the security and respect associated with it. They would probably prefer to think their work is relevant and appreciated. Consider a news item from Texas:

Rejection of help is widely known amongst people who sell sex of all ages, yet to question ideas about helping is frowned upon. It is said people who are at least trying to do good deserve credit. Do they have to be perfect? At any rate, they are not employed as soldiers or bankers, they are socially involved, at least they care. But for most social workers, the job is just a job. They don’t imagine themselves to be saints but do appreciate the security and respect associated with it. They would probably prefer to think their work is relevant and appreciated. Consider a news item from Texas:

Child sex trafficking seminar in Paris educates first responders

Child sex trafficking seminar in Paris educates first responders

“You would think that if you ran across a child that was being used for sex trafficking that they would stand up and say help me and that’s not the case,” said Paris Regional Medical Emergency Director Doug LaMendola. “They are so mentally reprogrammed into submissiveness that they won’t speak up.”

It must be frustrating when help is rejected, but inventing psychological reasons is a dodge to avoid wondering if the projects could be improved. Some psy excuses used with women who sell sex are brainwashing, Stockholm Syndrome and acting out. Now consider a news item from Chicago:

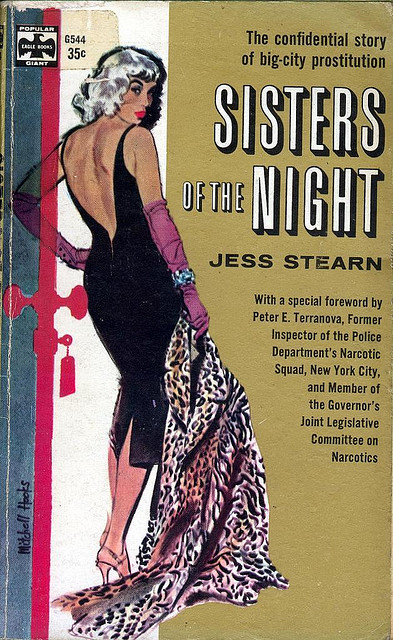

Who’s A Victim Of Human Sex Trafficking?

One recent Friday morning in a stuffy, crowded classroom at the Cook County jail in Chicago, a few women shared stories at a meeting of a group called Prostitution Anonymous. If they agree to get help, the women usually are not charged with prostitution in Cook County, though they may face other charges, from drug use to disorderly conduct.

Coercing people to participate in programmes is where social work touches bottom.

The idea that it’s impossible to change the lives of those in need unless they want them changed reveals a key assumption: that those in helping positions by definition already know what everyone needs. What happens if the person to be helped doesn’t accede to the helper’s proposition? Help fails, as it so often does in the oldest and commonest attempts worldwide to help women who sell sex, known as Exit Strategies, Diversion Programs and Rehabilitation. Consider recent news from Oklahoma:

The idea that it’s impossible to change the lives of those in need unless they want them changed reveals a key assumption: that those in helping positions by definition already know what everyone needs. What happens if the person to be helped doesn’t accede to the helper’s proposition? Help fails, as it so often does in the oldest and commonest attempts worldwide to help women who sell sex, known as Exit Strategies, Diversion Programs and Rehabilitation. Consider recent news from Oklahoma:

Teen prostitute leaves shelter to return to street life

“She was in protective custody and doesn’t want any help,” he said. “There is no indication of a drug history. That’s the life she preferred. There is no telling how much money she was making.”

Woodward said the teenager comes from a rough family in the Tulsa area. “She doesn’t like her family, and she didn’t want us to contact her family,” he said.

Most women and young people who sell sex are simply not attracted by the alternative occupations or ‘homes’ offered that provide no flexibility, no autonomy, no street life, no way to have fun and pitiful money. Social workers can always point to people they know who appreciated some such project, but mainstream media provide examples of failure every week. The significant refusal here is on the social-work side, where not believing what people say they need guarantees that the situation for sex workers stays the same, despite endless hand-wringing and rhetoric about the need to help them.

–Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist