I wrote Prostitution Law and the Death of Whores for Jacobin (A magazine of culture and polemic) to reach a different audience, perhaps some left-leaning folks who don’t know it’s possible to talk about prostitution, sex work, trafficking and migration in interesting ways.

I wrote Prostitution Law and the Death of Whores for Jacobin (A magazine of culture and polemic) to reach a different audience, perhaps some left-leaning folks who don’t know it’s possible to talk about prostitution, sex work, trafficking and migration in interesting ways.

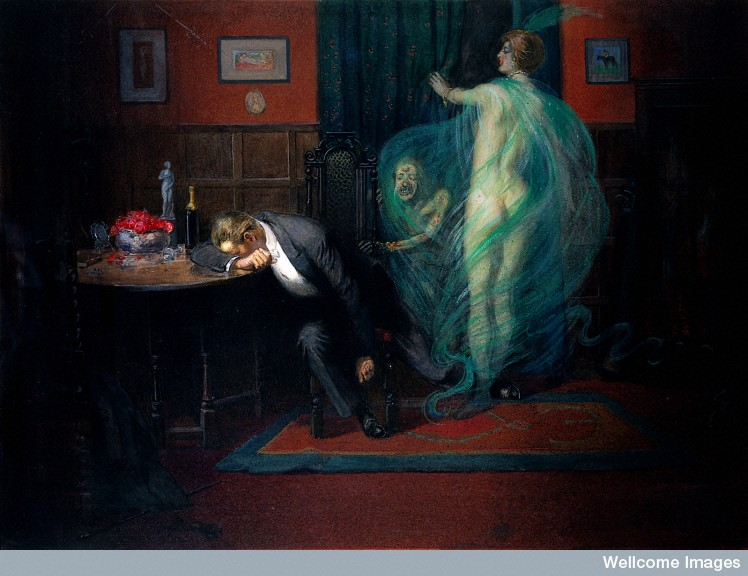

The piece was very hard to write, not only because I was shocked by the death of someone I knew but because I wanted to bring together many themes without going too deep into any. The exception was perhaps the idea of stigma. I said

Many people have only a vague idea what the word stigma means. It can be a mark on a person’s body – a physical trait, or a scarlet letter. It can result from a condition like leprosy, where the person afflicted could not avoid contagion. About his selection of victims Sutcliffe said he could tell by the way women walked whether or not they were sexually “innocent”.

Stigma can also result from behaviors seen to involve choice, like using drugs. For Erving Goffman, individuals’ identities are “spoiled” when stigma is revealed. Society proceeds to discredit the stigmatized – by calling them deviants or abnormal, for example. Branded with stigma, people may suffer social death – nonexistence in the eyes of society – if not physical death in gas chambers or serial killings.

I won’t be creating a hierarchy of who suffers stigma most but do believe stigmas vary in how they manifest and feel to those involved as well. There are diverse views amongst people who study the subject. For me in studying the stigma that goes to women who sell sex, there is an extra element not present in other stigmas (HIV, homosexuality, drug use): the impulse to control women sexually, keep them in separate categories of Good and Bad based on their sexual behaviour. This doesn’t mean they ‘suffer more’, that’s not my point. I’m simply interested in the contribution a longtime social impulse makes to the belief amongst so many that women who sell sex are actually (and deplorably) different from women who don’t.

I also am interested in a consequence of stigmatisation more than the mark itself – the mechanism of disqualification. For those who believe the stigma is real, women who carry it are considered not able to speak for or even know themselves, which provides the excuse to disqualify anything they say about how they feel and what they want. Helpers, saviours and police choose to believe – not disqualify – statements that tally with their own views of what women (must) experience. It is distressing to watch so much disqualification of women’s words and deeds, and why I ended the piece with the call that we assume that what all women say is what they mean.

Salon ran the same piece under The sex worker stigma: How the law perpetuates our hatred (and fear) of prostitutes. Of course this title is catchier and better for a more mainstream audience. But I did not write either word, hatred or fear, in the piece itself, so for me the change is jarring. Under the title, Salon wrote Our society turns a blind eye to the murder of sex workers, deeming them less than human. Why is that? I never said stigma makes people less than human, so here we have an editor who may or may not have actually read the essay imposing ideas not held by the author herself. Fear-and-hatred are not a synonym for stigma; there are many more fears and hatreds in the world than stigmas.

Salon ran the same piece under The sex worker stigma: How the law perpetuates our hatred (and fear) of prostitutes. Of course this title is catchier and better for a more mainstream audience. But I did not write either word, hatred or fear, in the piece itself, so for me the change is jarring. Under the title, Salon wrote Our society turns a blind eye to the murder of sex workers, deeming them less than human. Why is that? I never said stigma makes people less than human, so here we have an editor who may or may not have actually read the essay imposing ideas not held by the author herself. Fear-and-hatred are not a synonym for stigma; there are many more fears and hatreds in the world than stigmas.

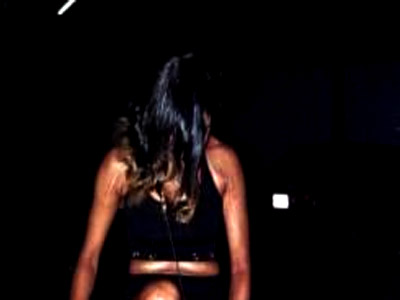

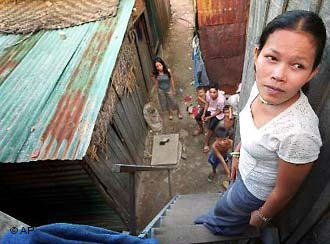

The photo Salon ran shows a woman standing in a pose associated with street prostitution but not wearing the uniform that I called ‘the outward sign of an inner stain’. Perhaps that move is in line with their progressive use of sex workers in the title. But what about the caption underneath it? A worker in prostitution who goes by the name Violet in downtown San Francisco. I polled many people afterwards and all were unfamiliar with the term worker in prostitution. In the sex wars, those who denounce prostitution refuse to think of it as work and sex workers often reject the term prostitution.

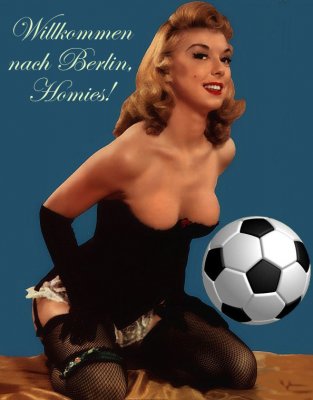

One way to try to destroy the stigmatising distinction between Good and Bad women proclaims that all women are whores, which I like better than whores’ insisting they are Good, but I guess they come to the same thing. Here are two recent photos showing the first strategy, one in Germany (Wir sind alle prostitutas-We are all prostitutes, where the Spanish prostitutas indicates solidarity with migrant sex workers, and another in Perú (Todos tenemos algo de puta – We all have a bit of the whore in us).

One way to try to destroy the stigmatising distinction between Good and Bad women proclaims that all women are whores, which I like better than whores’ insisting they are Good, but I guess they come to the same thing. Here are two recent photos showing the first strategy, one in Germany (Wir sind alle prostitutas-We are all prostitutes, where the Spanish prostitutas indicates solidarity with migrant sex workers, and another in Perú (Todos tenemos algo de puta – We all have a bit of the whore in us).

–Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist