Charles II lifted the Puritan ban on theatre-going, and by 1700 London was sex-capital of Europe. This walk starts with the stage at a time when all actresses were assumed to be prostitutes and theatres a place for clients to find them. We pass through areas where street-walkers and bawdy houses were closely linked with playhouses, and we hear about high-class masquerades where actress-courtesans like Sophia Baddely might appear. There are the bawds who kept houses, the women who worked in them, like Nell Gywn and Sally Salisbury, and Harris’s List, where they might advertise. We hear about homosexual Molly Houses as well as Jelly Houses, Coffee Houses and Bagnios. Links between corrupt government officials and criminals formed the plot of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera in 1728, with its cast of thief-takers, highwaymen, pickpockets and sex workers like Jenny Diver who met in flash houses where they spoke a secret language. The unscrupulous Society for the Reform of Manners tried to close down vice, but things began to change when Social Reformers said women selling sex were victims needing rescue. The walk starts in Lincoln’s Inn Fields and passes through Covent Garden and surrounding streets like Drury Lane, where ordinary folks lived who sold sex – orange women, flower girls and patrons of dance halls. The underworld called this red-light area where you might meet Edgworth Bess the Hundreds of Drury.

Charles II lifted the Puritan ban on theatre-going, and by 1700 London was sex-capital of Europe. This walk starts with the stage at a time when all actresses were assumed to be prostitutes and theatres a place for clients to find them. We pass through areas where street-walkers and bawdy houses were closely linked with playhouses, and we hear about high-class masquerades where actress-courtesans like Sophia Baddely might appear. There are the bawds who kept houses, the women who worked in them, like Nell Gywn and Sally Salisbury, and Harris’s List, where they might advertise. We hear about homosexual Molly Houses as well as Jelly Houses, Coffee Houses and Bagnios. Links between corrupt government officials and criminals formed the plot of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera in 1728, with its cast of thief-takers, highwaymen, pickpockets and sex workers like Jenny Diver who met in flash houses where they spoke a secret language. The unscrupulous Society for the Reform of Manners tried to close down vice, but things began to change when Social Reformers said women selling sex were victims needing rescue. The walk starts in Lincoln’s Inn Fields and passes through Covent Garden and surrounding streets like Drury Lane, where ordinary folks lived who sold sex – orange women, flower girls and patrons of dance halls. The underworld called this red-light area where you might meet Edgworth Bess the Hundreds of Drury.

Tag Archives: walking

Which 14th-century working women did sex work?

I’m speaking at Salon for the City on Thursday night this week. The title of the salon is London: City of Sex Work, and my co-speaker is Julie Peakman. I’ll be focusing on the 14th century in Southwark, but it’s not all about the Bankside brothels. In fact my annoyance about how guides usually talk about the Bankside was a reason I got into the guiding business. The picture shows me there along the river.

I’m speaking at Salon for the City on Thursday night this week. The title of the salon is London: City of Sex Work, and my co-speaker is Julie Peakman. I’ll be focusing on the 14th century in Southwark, but it’s not all about the Bankside brothels. In fact my annoyance about how guides usually talk about the Bankside was a reason I got into the guiding business. The picture shows me there along the river.

In a previous career as activist-public speaker about migration, prostitution law and sex workers’ rights I focused on the present day on an international level, because women who migrate from all parts of the world to all other parts of the world often sell sex at some point. They may have planned to or they may have been duped into it. They may hate or only tolerate selling sex – or they may find it works for them better than the other (less than desirable) jobs open to them as undocumented wanderers or purposeful migrants.

When I was doing a PhD I did long research into how societies have thought about prostitution, to understand the contemporary resistance to accepting sex work as a job. My book Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Rights and the Rescue Industry includes a historical chapter which as a primer I still recommend. In our own time the conflict about this topic feels endless and unproductive, a fight about what feminism is supposed to be. I was glad to leave that behind.

When I was doing a PhD I did long research into how societies have thought about prostitution, to understand the contemporary resistance to accepting sex work as a job. My book Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Rights and the Rescue Industry includes a historical chapter which as a primer I still recommend. In our own time the conflict about this topic feels endless and unproductive, a fight about what feminism is supposed to be. I was glad to leave that behind.

But when I decided to guide, a central motivation was to include people nearly always omitted from historical walks – not to say from historical accounts in general, where poorer working people form an inanimate background to Great Events. Including ordinary working people means including those who sell sex in many different settings and forms, in whatever era and place the walk is about.

For my walk Scratching Out a Living: the Medieval Female Proletariat I created six women working near the Thames in 14th-century Southwark. Their characters are based on long research, including in the world of illuminated manuscripts. I’ve written about this research, which led to creating a walk that first appeared as part of the Totally Thames Festival in September last year.

For my walk Scratching Out a Living: the Medieval Female Proletariat I created six women working near the Thames in 14th-century Southwark. Their characters are based on long research, including in the world of illuminated manuscripts. I’ve written about this research, which led to creating a walk that first appeared as part of the Totally Thames Festival in September last year.

I’ll be talking about this at the Salon: how poorer women got by in a legal and social context that was all against them. Inevitably every one of them has some relation to the sex industry — and I use that term advisedly because everything isn’t now and wasn’t then ‘prostitution’. The brief talk aims to show how commercial sex was everywhere in the fabric of everyday life, as I believe it is now. The above picture is from marginalia in the Luttrell Psalter, catalogued as Add. 42130, f.63 at the British Library. Commentators usually say the woman on the left is a prostitute because she is vainly combing her hair and looking in a mirror (. . .)

I’m doing the walk again on 2 May as an after-work event with fellow-guide Rob Smith, who provides the Big-History context for the lives of the female proletariat. It’s a wonderful walk through areas you may think you already know (here for instance by Southwark Cathedral and Borough Market), and it ends in a riverside pub for refreshment and further conversation, which has become an integral part of my walks. I want to hear what everyone has to say. You can book here.

I’m doing the walk again on 2 May as an after-work event with fellow-guide Rob Smith, who provides the Big-History context for the lives of the female proletariat. It’s a wonderful walk through areas you may think you already know (here for instance by Southwark Cathedral and Borough Market), and it ends in a riverside pub for refreshment and further conversation, which has become an integral part of my walks. I want to hear what everyone has to say. You can book here.

Follow me on Eventbrite to hear when new walks and new dates are published. And I’ve now got 20 reviews on TripAdvisor, if you want to hear how walkers have seen my walks.

emma

—Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist

Gin Lane: Thieves and Thief-takers in the Night-Cellars of Seven Dials

Now it’s trendy and pretty, but 18th-century Seven Dials was notorious for poverty and crime. With no organised police force, thieves, highwaymen and fences bribed those hired to catch them, meeting in low-down dives where they spoke a secret language called flash. The notoriously corrupt Jonathan Wild captured thief Jack Sheppard more than once, but Jack made dramatic escapes from prison aided by his sexworker-partner Edgworth Bess.

Now it’s trendy and pretty, but 18th-century Seven Dials was notorious for poverty and crime. With no organised police force, thieves, highwaymen and fences bribed those hired to catch them, meeting in low-down dives where they spoke a secret language called flash. The notoriously corrupt Jonathan Wild captured thief Jack Sheppard more than once, but Jack made dramatic escapes from prison aided by his sexworker-partner Edgworth Bess.

With gin selling at a penny a glass, carousing was full-on in areas outsiders called rookeries, thieves’ kitchens, the Holy Land (because of the Irish presence) and, for Drury Lane’s red-light zone, Little Sodom. A range of middle-class spies, social investigators, reporters and slum-tourists came to look and sometimes participate in goings-on they found appalling and titillating. John Gay portrayed popular hero Jack Sheppard and Public Enemy Jonathan Wild in the characters of Captain MacHeath and Mr Peachum, in The Beggar’s Opera, London’s favourite theatre-piece throughout the 18th century. What fun!

Scratching out a living by the river: The Medieval Female Proletariat

Written history records only the rich and famous, because poor women do nothing interesting – right? No! Ordinary working women had interesting, varied lives in the Middle Ages and this walk sets out to show what they were like. You’ll meet 6 women who lived and worked near the Thames in Southwark in the 14th century: scullery maid, victualler, laundress, alewife, sex worker, huckster.

Written history records only the rich and famous, because poor women do nothing interesting – right? No! Ordinary working women had interesting, varied lives in the Middle Ages and this walk sets out to show what they were like. You’ll meet 6 women who lived and worked near the Thames in Southwark in the 14th century: scullery maid, victualler, laundress, alewife, sex worker, huckster.

We’ll start at the south end of London Bridge and end on the north side of the river near the Millenium Bridge. The distance is about 3 miles taking 2.5 hours or a bit more depending on crowds. We’ll be walking on pavements, not the foreshore, so no special shoes are required, but there are numerous stairs to climb up and down and some bumpy cobbles, so this walk isn’t recommended if you have mobility issues.

Laura Agustín is a medieval historian and anthropologist interested in illuminating the lives of unnamed people in history. On this walk she’s joined by Rob Smith, longtime London guide and friend, in a dialogue about what makes history.

Victorian Visions of Women in Art, from Goddesses to Fallen Women

In Victorian England everyone knew things were bad for women: few rights of their own, a domestic ideology mandating stay-at-home motherhood, no available jobs but as maid, nanny or sex worker. In a couple of rooms the Tate displays floor-to-ceiling the wonderfully varying responses from English artists, mixing schools of artistic theory and style. Academic painters ignored the issues, sticking to noble subjects and classical nudes; the Pre-Raphaelites felt bad about the injustices, portraying beautiful if forlorn medieval heroines; and Social Realists painted women as victims of patriarchy. How many of the paintings are great? Should art take moral positions? No paintings suggested women might be protagonists of interesting creative lives. Come look at this immersive display of 19th-century art and help figure out how the confusion lives on in the present day. All gender-identities are welcome on this walk – think of women as an historical term!

In Victorian England everyone knew things were bad for women: few rights of their own, a domestic ideology mandating stay-at-home motherhood, no available jobs but as maid, nanny or sex worker. In a couple of rooms the Tate displays floor-to-ceiling the wonderfully varying responses from English artists, mixing schools of artistic theory and style. Academic painters ignored the issues, sticking to noble subjects and classical nudes; the Pre-Raphaelites felt bad about the injustices, portraying beautiful if forlorn medieval heroines; and Social Realists painted women as victims of patriarchy. How many of the paintings are great? Should art take moral positions? No paintings suggested women might be protagonists of interesting creative lives. Come look at this immersive display of 19th-century art and help figure out how the confusion lives on in the present day. All gender-identities are welcome on this walk – think of women as an historical term!

The tour takes about an hour and a half, after which there’s an option to join me in the café for further discussion, head-shaking and laughter.

History from Below in Camden Walks

What do you think about when you hear the name Primrose Hill? Good pubs, celebrity-residents, the view over London? For me it’s a neighbourhood that looks as it does because of the building of the Regent’s Canal and the railways.

When the canal was being extended into the area, developers foresaw no obstacle to their plans for elegant houses like those along Regent’s Park: the digging was to be by hand, and the heaps of soil produced might be useful. But then they saw what building the railway did to nearby Camden Town – what Dickens in Dombey and Son called mud and ashes, frowzy fields, dunghills, dustheaps and ditches. When the soot thrown up turned to grime on the eastern edge of the new neighbourhood, all bets were off: Developers switched to building terraced houses.

Who did all the digging and throwing, who sweated and toiled to make the great engineering feats reality? They were called many names – Excavators, Cutters, Diggers, Bankers, Navigators – before Navvies was printed in a news item of 1830 and the name stuck. These itinerant workers became almost mythic figures, considered mysterious and fearsome because of how they lived: not in settled families, camping wherever the work decreed, swanning into streets and pubs in eye-catching dress.

To focus on folks like the navvies is why I became a guide: to tell histories of those often treated like props in the background on the stage of Big Events. This tradition is called History from Below, and it makes a great way to see with new eyes neighbourhoods you think you already know.

There are challenges, because whoever was recording events at the time almost always overlooked the labourers, whether they were scullery maids or navvies. But there are ways to find out, and tracking them down is my delight.

Walk the story of Primrose Hill and the Navvies on 2 March 2024.

My moniker the Naked Anthropologist dates from decades when I was a researcher and activist with undocumented women. The anthropological stance of observing people as part of their own culture with its own logic allowed me to do the work. Naked Anthropology means Plain Speaking on subjects often ignored or swept under the rug; History from Below tries to do the same thing.

Consider Holborn, that shrine of eminent legal institutions and insurance titans. Less grand histories lurk beneath that surface. One of them, the migration of Italians, is well recognised, but for anyone interested in migration the area is a prime example of how migrating peoples move in, live side-by-side and mix with other ethnic or national groups and then move on again.

The history of streets from the Fleet Ditch to Grays Inn Road and from High Holborn to north of the Clerkenwell Road can be told through migrations of people looking for ways to make new lives, using their skills when possible or taking whatever jobs were going. Poor Irish, freed slaves, Jewish diamond-cutters and migrants from the rest of England all lived in this area when it held no appeal for wealthy Londoners. Some migrants didn’t want to come and others did: All have left their marks.

Come along and walk Historic Workingclass Migrations to London on 17 March 2024.

See my other walks coming up, both in and out of Camden, on Eventbrite.

This article was first published in the Camden Guides newsletter of 17 February 2024.

–Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist

Essex Estuaries – From Dovercourt to Harwich Pier

I’m joined by guide Rob Smith for this walk from the seaside town of Dovercourt to Harwich Pier, exploring connections with the sea. On this tour along the Essex coast at the mouth of the River Stour, we will walk from Dovercourt to the pier at Harwich, a traditional point of arrivals and departures. The train journey from London takes 1 hour and 20 minutes.

I’m joined by guide Rob Smith for this walk from the seaside town of Dovercourt to Harwich Pier, exploring connections with the sea. On this tour along the Essex coast at the mouth of the River Stour, we will walk from Dovercourt to the pier at Harwich, a traditional point of arrivals and departures. The train journey from London takes 1 hour and 20 minutes.

Rob will be talking about lighthouses, of which there are some nice examples on the walk, and we will also be walking past the repair yard belonging to Trinity House, who look after navigational aids around the UK. Rob will also talk about shipbuilding and we will walk past the wonderful treadwheel crane built in 1667. Rob will talk about some of the ships built in Harwich, the most famous being the Mayflower, which is believed to have been built in the towns shipyards. Thames barges were also constructed here.

Laura will talk about able seamen in the Age of Sail, whose jobs involved running up rigging during storms, manning guns during battles and dealing with boredom in the doldrums. Men (and some cross-dressed women) volunteered for a life at sea in large numbers, and some were forced through impressment when the navy needed them. Laura will also mention Arthur Ransome’s intrepid Swallows who Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea and Harwich’s connections to colonies across the Atlantic.

We’ll take in views across the estuary to the container port at Felixstowe, while the town of Harwich has some fine Georgian architecture and some good pubs to explore after the walk.

The walk is about two miles and finishes at Harwich Pier which is a short walk from Harwich Town Station. Wear good shoes for the seaside path.

Slumming: Middle Class Tours to Deplore the Poor

Now it’s trendy and pretty but Seven Dials was notorious for poverty and crime in the eyes of the Middle Classes. You’ll see where poorer working folks lived and hear how they were considered sub-human and dangerous, called vagrants, beggars, ragamuffins and street arabs living in Thieves’ Kitchens and Little Sodom. You’ll hear how they were first spied on and then the objects of slum tours, with the bourgeoisie gawking at street life and dosshouses where the poor could spend the night hanging over a rope. John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, which opened in 1728, made fun of the idea that the upper classes were more moral and human than the poor, but that was the belief of those who rarely if ever even saw them.

Now it’s trendy and pretty but Seven Dials was notorious for poverty and crime in the eyes of the Middle Classes. You’ll see where poorer working folks lived and hear how they were considered sub-human and dangerous, called vagrants, beggars, ragamuffins and street arabs living in Thieves’ Kitchens and Little Sodom. You’ll hear how they were first spied on and then the objects of slum tours, with the bourgeoisie gawking at street life and dosshouses where the poor could spend the night hanging over a rope. John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, which opened in 1728, made fun of the idea that the upper classes were more moral and human than the poor, but that was the belief of those who rarely if ever even saw them.

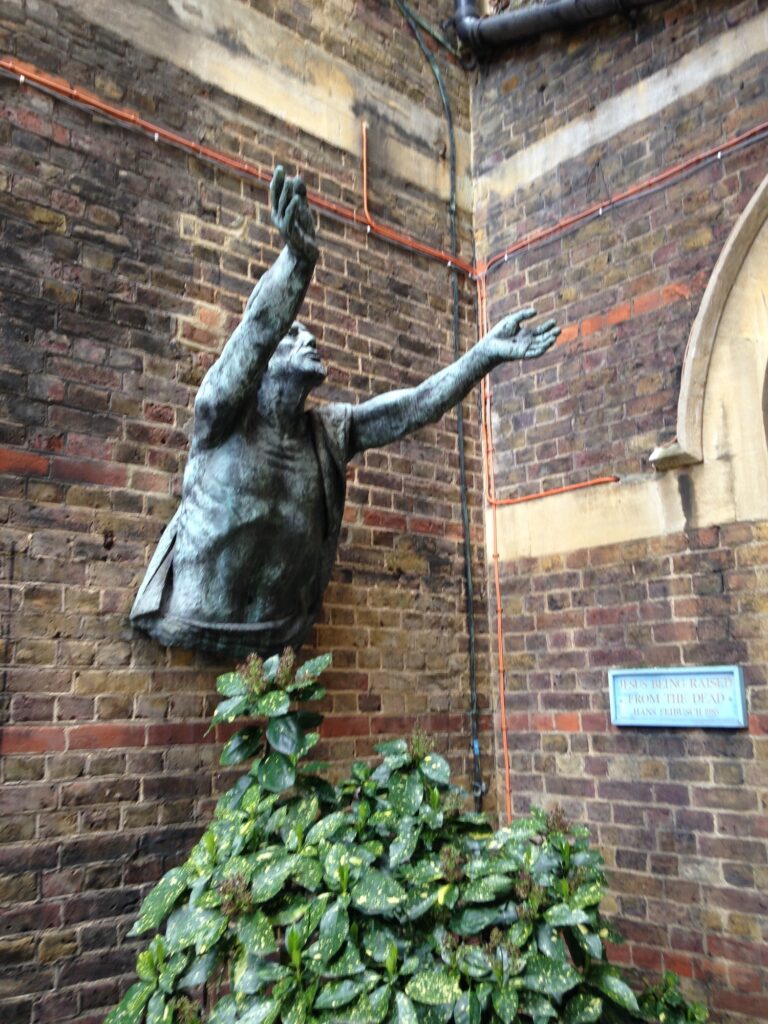

You’ll see buildings set up to save the badly-off from their misery: But were they always so miserable? This tour looks at middle-class prejudices and attempts to improve things that often punished the poor instead.

An Interest in the Backside of Things

All our lives society has been represented to us as a hierarchy or pyramid in which the rich are located at the top, the middle class sits underneath and workers sprawl at the bottom. Anything lower than the bottom is called underclass, a lot of dysfunctional nobodies. Isn’t it still assumed everyone is striving to move up this ladder? Failure is constructed as happening downwards, a falling into an abyss – the word Jack London and Mary Higgs used to describe how the poor were forced to live.

All our lives society has been represented to us as a hierarchy or pyramid in which the rich are located at the top, the middle class sits underneath and workers sprawl at the bottom. Anything lower than the bottom is called underclass, a lot of dysfunctional nobodies. Isn’t it still assumed everyone is striving to move up this ladder? Failure is constructed as happening downwards, a falling into an abyss – the word Jack London and Mary Higgs used to describe how the poor were forced to live.

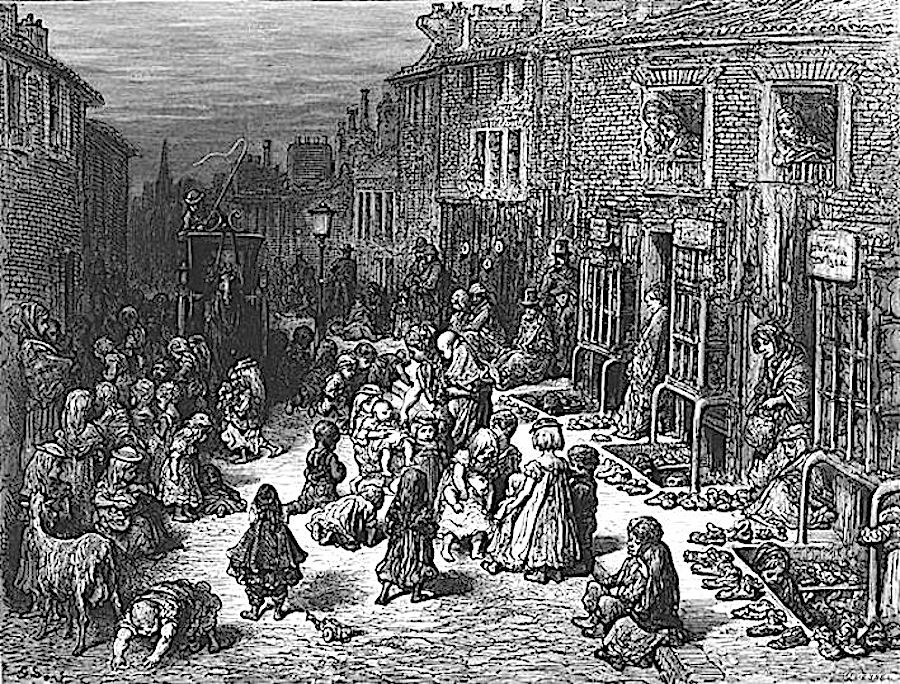

For my history-walk about the poor in St Giles I did research on social reformers’ fear of cellars. How can that be? you’ll say, why, the best people now live in garden flats. From the 18th century for a long time cellar-living was considered to be appalling by those living well above ground. Cellar-dwellers were conceived of as more animal than human, an indistinguishable mass likened to moles and worms. Rescuers and reformers sought to raise up the miserable from their low position, Fallen Women first. In Gustave Doré’s drawing of the market in Dudley Street, the cellars are surrounded by old shoes and boots. Some see misery here; others don’t. Doré clearly felt sympathy with the cellar-dwellers.

For my history-walk about the poor in St Giles I did research on social reformers’ fear of cellars. How can that be? you’ll say, why, the best people now live in garden flats. From the 18th century for a long time cellar-living was considered to be appalling by those living well above ground. Cellar-dwellers were conceived of as more animal than human, an indistinguishable mass likened to moles and worms. Rescuers and reformers sought to raise up the miserable from their low position, Fallen Women first. In Gustave Doré’s drawing of the market in Dudley Street, the cellars are surrounded by old shoes and boots. Some see misery here; others don’t. Doré clearly felt sympathy with the cellar-dwellers.

What if instead of a hierarchy low-to-high we think of sides of the story: that the version we hear of current events and history is the Front Side, the official version told from the point of view of those who have the greatest communications-power. Their view places themselves at the centre, where stated aims and values are not questioned. The facade of the palace.

But for every such frontside, there are backsides, other realities, and that’s where the goings and comings of most people take place. Out of the limelight and usually out of historical accounts, too.

That’s the meaning in the title of my tour The Backside of Knightsbridge Barracks. The front of the barracks-complex faces Hyde Park; horse guards in military regalia on their way to perform ceremonial duties exit under an elaborate late-19th-century pediment. A classic Frontside.

That’s the meaning in the title of my tour The Backside of Knightsbridge Barracks. The front of the barracks-complex faces Hyde Park; horse guards in military regalia on their way to perform ceremonial duties exit under an elaborate late-19th-century pediment. A classic Frontside.

The back of the buildings face onto where for several hundred years poorly-paid soldiers, their girlfriends, wives, children and hangers-on scraped together livings. Knightsbridge (the street) was scene of goings-on that wealthy folks called disorderly, meaning drunkenness, carousing, noise, fights, streetwalking, numerous pubs and two major music halls whose raucous style of entertainment suited the working class. Sites of Low Pleasures, according to those set on raising the tone of the area.

The back of the buildings face onto where for several hundred years poorly-paid soldiers, their girlfriends, wives, children and hangers-on scraped together livings. Knightsbridge (the street) was scene of goings-on that wealthy folks called disorderly, meaning drunkenness, carousing, noise, fights, streetwalking, numerous pubs and two major music halls whose raucous style of entertainment suited the working class. Sites of Low Pleasures, according to those set on raising the tone of the area.

The walk looks at the houses where servants and tradespeople lived in what were built as mean and cheap little houses but are today the height of fashion. I talk about stable lads and grooms, dressmakers and laundresses, all the trades needed to service the rich. Two well-known courtesans appear, both with good manners and nice clothes but always trying to persuade their admirers to grant them annuities to live on and houses to live in. They don’t seem to be working-class, but they were certainly working. And there’s the story of a lowly horse guard and his dollymop-turned-wife, struggling to make ends meet. One Frontside superstar does appear, the Duke of Wellington, because he got in a fracas with one of the courtesans. Oh and his superstar horse Copenhagen appears when we’re walking in Rotten Row in the park. It’s a horsey walk.

The walk looks at the houses where servants and tradespeople lived in what were built as mean and cheap little houses but are today the height of fashion. I talk about stable lads and grooms, dressmakers and laundresses, all the trades needed to service the rich. Two well-known courtesans appear, both with good manners and nice clothes but always trying to persuade their admirers to grant them annuities to live on and houses to live in. They don’t seem to be working-class, but they were certainly working. And there’s the story of a lowly horse guard and his dollymop-turned-wife, struggling to make ends meet. One Frontside superstar does appear, the Duke of Wellington, because he got in a fracas with one of the courtesans. Oh and his superstar horse Copenhagen appears when we’re walking in Rotten Row in the park. It’s a horsey walk.

The Backside of Knightsbridge Barracks happens on Saturday 20 January.

My other walks show other kinds of backsides:

Sunday 28 January is about The Medieval Female Proletariat in Southwark.

Saturday 10 February takes on the connections between London’s Sex Industry and the Stage in the Long 18th Century.

On Saturday 2 March it’s Primrose Hill, where navvies built canal and railways.

It’s right in the title on Sunday 17 March: Working-class Migrations to Holborn: Irish, Italian, African, Jewish

And I just published a new walk, Disgraceful Women of Old St John’s Wood, that shows the backside of that ultimate bourgeois value, Respectability.

—Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist

Disgraceful Women of Old St John’s Wood

In St John’s Wood Alternative Lifestyles were the norm, but nearby Lisson Grove saw the first sex-slave scandal, of young Eliza Armstrong. This walk begins 200 years ago in St John’s Wood, where family arrangements routinely diverged from Victorian rules of respectability. What did it mean to be a Kept Woman? Was it only disreputable or an act of shameful immorality? Some mistresses were movers and shakers, like Harriet Howard who financed the return of Louis Napoleon to the French throne. Novelist George Eliot lived placidly for many years with someone else’s husband, not far from a brothel where sex workers were known as laundresses. A bigamous Agapemonite minister lived with multiple rich unmarried female followers. All this took place in a suburb built with high walls and thick trees to ensure privacy and discretion.

We walk south into Lisson Grove, considered a Victorian slum, where journalist WT Stead staged a scandal he called The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon, when he bought Eliza Armstrong from her mother to prove it could be done.

How much did social class determine whether society was appalled by alternative sexual arrangements? Were unmarried women with lovers heroines or victims? Come on this walk to consider scandals of 200 years ago that might sound familiar today, and at the same time join up two neighbourhoods you never thought about together before.

Essex Estuaries – The Stour from Manningtree to Mistley

Laura is joined by guide Rob Smith for this walk along the Stour Estuary looking at a 17th-century witch-craze and the women targeted.

Laura is joined by guide Rob Smith for this walk along the Stour Estuary looking at a 17th-century witch-craze and the women targeted.

On this walk along part of the Stour Estuary Laura will tell the story of women accused of witchcraft during a 17th-century craze that played out in the three villages of Lawford, Manningtree and Mistley. She’ll reveal exactly what kinds of women were targeted and talk about why, including the opportunism of local men like Matthew Hopkins. Rob will talk about Mistley Quay , a port where ships were built in the 18th century and now site of Britain’s largest malt factory. The walk also passes Mistley Towers a surviving part of a church designed by Robert Adam.

The walk is about 3 miles long and includes some country paths as well as town walking. We end at Mistley, and there will be a short pub stop at the half-way point. The walk crosses some open fields, so may be muddy, so boots or high trainers with good soles are needed.

Manningtree is about one hour by train from Liverpool Street Station.

Scratching out a living by the river: The Medieval Female Proletariat

How do we know how poor women lived in the Middle Ages when historians have ignored them? Walk along the river and meet 6 medieval women.Written history records only the rich and famous, and poor women did nothing interesting – right? So how did ordinary women get along? In this walk you’ll meet 6 women who lived and worked near the Thames in Southwark in the 14th century: scullery maid, victualler, laundress, alewife, sex worker, huckster. Long sessions in the British Library Reading Rooms enabled – and drove – me to create these characters.

How do we know how poor women lived in the Middle Ages when historians have ignored them? Walk along the river and meet 6 medieval women.Written history records only the rich and famous, and poor women did nothing interesting – right? So how did ordinary women get along? In this walk you’ll meet 6 women who lived and worked near the Thames in Southwark in the 14th century: scullery maid, victualler, laundress, alewife, sex worker, huckster. Long sessions in the British Library Reading Rooms enabled – and drove – me to create these characters.

We’ll start at the south end of London Bridge and end on the north side of the river near the Millenium Bridge. The distance is about 3 miles taking about 2 hours. We’ll be walking on pavements, not the foreshore, so no special shoes are required. There are numerous stairs to climb up and down with no alternate route, so this walk isn’t recommended if you have mobility issues.

Essex Estuaries – The Roach and Rochford

On this walk I’m joined by friend and guide Rob Smith. This tour around Rochford and the River Roach will pass Rochford Hall, once owned by oft-maligned Tudor courtier Richard Rich, the parish church and the surrounding golf course. Rochford was a hotbed of Protestantism, and we’ll talk about how Nonconformists differed, from Congregationalists to Puritans, Methodists and the Peculiar People.

On this walk I’m joined by friend and guide Rob Smith. This tour around Rochford and the River Roach will pass Rochford Hall, once owned by oft-maligned Tudor courtier Richard Rich, the parish church and the surrounding golf course. Rochford was a hotbed of Protestantism, and we’ll talk about how Nonconformists differed, from Congregationalists to Puritans, Methodists and the Peculiar People.

After a tour around the town looking at some fine houses, including one of the oldest in England, there will be a short pub stop. The second part of the walk goes along the River Roach, past the now derelict flour mill and live saltmarshes into the estuary to hear about the perils of riverside mud, with the aid of Susan Hill’s Woman in Black. Birds abound.

The walk is about five miles and could involve some muddy paths, so boots or high trainers with good soles are needed. Rochford is about one hour by train from Liverpool Street Station.

Historic Working-class Migrations: Irish, Italian, African, Jewish

People migrating to work in a city like London may begin settling together in ghettos, but eventually they mix. Working-class migrants, often maligned as ‘economic migrants’, do business, make families, invent objects, bring pleasures, help each other, fight and die together. One old area of central London shows strong and sympathetic traces of the migrations of poorer folk from the late-18th to 20th centuries from near and far, including from within England itself. The walk begins in the Fleet Ditch and works its way uphill through early Italian and Irish settlements in Saffron Hill into areas of more mixing, taking note of Blacks from Africa via the West Indies and ending with Jewish migrations from numerous locations that made Hatton Garden’s Diamond Street.

People migrating to work in a city like London may begin settling together in ghettos, but eventually they mix. Working-class migrants, often maligned as ‘economic migrants’, do business, make families, invent objects, bring pleasures, help each other, fight and die together. One old area of central London shows strong and sympathetic traces of the migrations of poorer folk from the late-18th to 20th centuries from near and far, including from within England itself. The walk begins in the Fleet Ditch and works its way uphill through early Italian and Irish settlements in Saffron Hill into areas of more mixing, taking note of Blacks from Africa via the West Indies and ending with Jewish migrations from numerous locations that made Hatton Garden’s Diamond Street.

Wind in the Willows – the Thames riverside from Richmond to Twickenham

Richmond is Sir David Attenborough’s favourite place on the planet!

Richmond is Sir David Attenborough’s favourite place on the planet!

Your fantasy of classic English countryside come true in the city. This stretch of the River Thames will put you in mind of boating holidays with Mole and Ratty. We see a wide village green, narrow lanes, the Tudor gatehouse of Richmond Palace, Old Deer Park. swimming birds and working boathouses. Crossing Richmond Bridge we walk southwards along the river, passing Marble Hill House and other mansions with parklands and gardens, along with an octagonal masterpiece building and the old White Swan pub, where we’ll take a break. On and off amongst the wildflowers and shrubbery you have views of the other side of the river, boats floating by and dogs paddling in the rushes. It’s dreamy, and near the end you’ll see the Naked Ladies statues and Eel Pie Island, famous for big-star rock concerts in the 1960s. You’ll also see the church and old lanes of Twickenham before coming to the high street, where we hop on a quick bus back to Richmond.

Primrose Hill and the Navvies

Primrose Hill is now one of London’s desirable areas, but it was born with the blood, sweat and toil that built the canal and railways.

Primrose Hill is now one of London’s desirable areas, but it was born with the blood, sweat and toil that built the canal and railways.

The neighbourhood radiates brilliant industrial solutions of Victorian engineers, but who built it? This walk puts hard-working navvies at the centre of the story and tells how the area developed in the face of the railway’s soot and smoke. The walk follows a beautiful stretch of the Regent’s Canal, and from the top of the famous hill you have great views over London. You’ll see railway landmarks as well as the artists’ studios and pastel-painted streets that came later, in one of which lives Paddington Bear. Primrose Hill cherishes a high street largely free of chain shops and numerous good pubs. It’s all minutes from Camden Market but feels miles away.

London’s Sex Industry and the Stage in the Long 18th Century

When the Puritan Protectorate ended in 1660, London’s sex industry grew wildly public and was linked to both theatres and the underworld.

When the Puritan Protectorate ended in 1660, London’s sex industry grew wildly public and was linked to both theatres and the underworld.

Charles II lifted the Puritan ban on theatre-going, and by 1700 London was sex-capital of Europe. This walk starts with the stage at a time when all actresses were assumed to be prostitutes and theatres a place for clients to find them. We pass through areas where street-walkers and bawdy houses were closely linked with playhouses, and we hear about high-class masquerades where actress-courtesans like Sophia Baddely might appear. There are the bawds who kept houses, the women who worked in them, like Nell Gywn and Sally Salisbury, and Harris’s List, where they might advertise. We hear about homosexual Molly Houses as well as Jelly Houses, Coffee Houses and Bagnios. Links between corrupt government officials and criminals formed the plot of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera in 1728, with its cast of thief-takers, highwaymen, pickpockets and sex workers like Jenny Diver who met in flash houses where they spoke a secret language. The unscrupulous Society for the Reform of Manners tried to close down vice, but things began to change when Social Reformers said women selling sex were victims needing rescue. The walk starts in Lincoln’s Inn Fields and passes through Covent Garden and surrounding streets like Drury Lane, where ordinary folks lived who sold sex – orange women, flower girls and patrons of dance halls. The underworld called this red-light area where you might meet Edgworth Bess the Hundreds of Drury.

I’ve won a prize: Women’s History Network Independent Researcher Grant

The best thing about this award is the fact that someone like myself can qualify at all. The Women’s History Network, recognising those doing rigorous research without being employed academics, have a separate grant category for us. I shared this prize with three other women.

The best thing about this award is the fact that someone like myself can qualify at all. The Women’s History Network, recognising those doing rigorous research without being employed academics, have a separate grant category for us. I shared this prize with three other women.

My proposal was to expand the research I did about working women in medieval Southwark to the same group in Norwich. While I was reading in the British Library, on and off for a couple of years, references often led me to Norwich’s development as a medieval urban centre, so of course I’ve wanted to research there. My questions would be the same I asked about Southwark: How did poorer women get by? What work did they do? Having comparable information from East Anglia will give shape and balance to the Southwark data about women I like to call the Medieval Female Proletariat.

One example from the Norfolk Record Office illustrates what I’d be looking for:

Norwich:File BL/CS 3/67

Proclamation by corporation of King’s Lynn ordering young unmarried women between 12 and 40, who have no visible means of living, to go out to service or be sent to the house of correction.

Singlewomen – the civil status assigned to women who’d never married – were considered loose cannon, prostitutes in the making, obvious troublemakers. Singlewomen couldn’t by definition be heads of households; they were told to become a servant in someone else’s household if they couldn’t manage to get married. As a wife, they would be ‘protected’ by husbands, which is another way to say they’d be kept in line.

This example also signals the connection between this project and my decades of previous research into migration: Women leave home to find new places to try to live without authority figures trying to crush them into being housemaids, unwilling wives or prisoners.

What did I promise to do with the results of this research? Why create a walk about it in Norwich of course. And include it in the Southwark walk and probably some other new walk I haven’t invented yet. It’s encouraging the Women’s History Network recognise walks as a good product of research.

So sometime this winter when prices are lower and the weather absolute crap, I’ll go to Norwich for some days and visit the cathedral to see in person this sculpture of a medieval laundress in the act of being robbed by a barefoot boy. She’s a roof boss in the cloister, one of very few representations of medieval women to be seen in a public English place.

So sometime this winter when prices are lower and the weather absolute crap, I’ll go to Norwich for some days and visit the cathedral to see in person this sculpture of a medieval laundress in the act of being robbed by a barefoot boy. She’s a roof boss in the cloister, one of very few representations of medieval women to be seen in a public English place.

And if there’s any way to stretch the money I’ll go to Portsmouth, too.

—Laura Agustín, The Naked Anthropologist

The Backside of Knightsbridge Barracks

History of working people in 18-19c Knightsbridge: Horse Guards, their girlfriends and families and two well-known courtesans. You’ll see the barracks from behind and from the front in Hyde Park, where the Household Cavalry Mounted Regiment leave for Changing the Guard ceremonies. Rotten Row was long the scene of high-society socialising, and you’ll hear about Skittles, the brilliant horsewoman who was courtesan to the rich and famous. The Duke of Wellington was client to demi-rep Harriette Wilson in these streets, and you’ll find out about a woman he tried to evict from her hut near the Serpentine when the Great Exhibition of 1851 was afoot. Horses of all kinds and the men who bred, groomed and bet on them are a strong presence. And there’s the story of a lowly horse guard and his dolly-mop-turned-wife in the back streets of this workers’ Knightsbridge quite unlike the one you usually hear about.

History of working people in 18-19c Knightsbridge: Horse Guards, their girlfriends and families and two well-known courtesans. You’ll see the barracks from behind and from the front in Hyde Park, where the Household Cavalry Mounted Regiment leave for Changing the Guard ceremonies. Rotten Row was long the scene of high-society socialising, and you’ll hear about Skittles, the brilliant horsewoman who was courtesan to the rich and famous. The Duke of Wellington was client to demi-rep Harriette Wilson in these streets, and you’ll find out about a woman he tried to evict from her hut near the Serpentine when the Great Exhibition of 1851 was afoot. Horses of all kinds and the men who bred, groomed and bet on them are a strong presence. And there’s the story of a lowly horse guard and his dolly-mop-turned-wife in the back streets of this workers’ Knightsbridge quite unlike the one you usually hear about.

The Beggar’s Opera – Lives of the Poor in Seven Dials

This walk through the central neighbourhood of St Giles uncovers a history of Londoners that weren’t famous, well-educated or well-heeled. You’ll see where poorer folks lived and worked, and hear how the middle classes considered them sub-human and dangerous, calling them vagrants, beggars, ragamuffins and street arabs living in rookeries, Thieves’ Kitchens and Little Sodom.

This walk through the central neighbourhood of St Giles uncovers a history of Londoners that weren’t famous, well-educated or well-heeled. You’ll see where poorer folks lived and worked, and hear how the middle classes considered them sub-human and dangerous, calling them vagrants, beggars, ragamuffins and street arabs living in rookeries, Thieves’ Kitchens and Little Sodom.

You’ll hear how they first spied on the poor and then went ‘slumming’ in their neighbourhoods, gawking at dosshouses where the poor could spend the night hanging over a rope or lying in a coffin. John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, which opened in 1728 at Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre, made fun of the idea that the upper classes were more moral and human than the poor.

You’ll see buildings set up to ‘rescue’ the poor from their misery – but were they always so miserable? This tour looks at middle-class prejudices and attempts to improve things that often punished the poor.