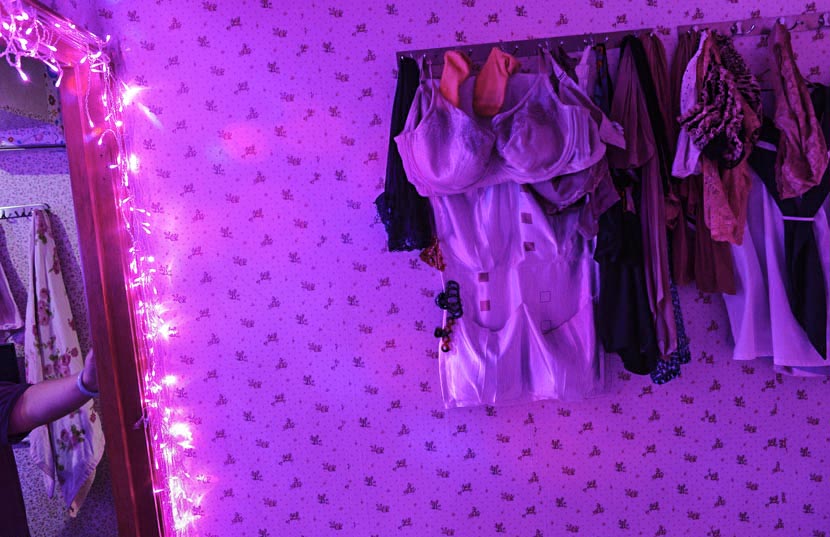

I know many folks who relate to the idea of sex work as one of their jobs and to sexworker as one of their identities. But I have known many more who sell sex and don’t feel like this. Of course it’s possible to ask questions that appear to prove interviewees always feel it’s a job: many social scientists study occupations and need everyone to have a clear label. Those of us who’ve sat and listened at length to people’s stories know things are a lot muddier than that. But, you might say, hold on, look at what are captioned ‘tools of the trade’ in the photo here: don’t they prove it’s a job for the woman using them?

I think back to most of my own jobs: Did I ever feel secretary was my identity? Or dogwalker? (That could be me in the 1967 photo in Central Park though I don’t ever remember walking so few dogs at once.) Even when I had the title Managing Editor I never felt it was who I was.

I think back to most of my own jobs: Did I ever feel secretary was my identity? Or dogwalker? (That could be me in the 1967 photo in Central Park though I don’t ever remember walking so few dogs at once.) Even when I had the title Managing Editor I never felt it was who I was.

In China the word xiaojie means Miss or young lady. Many women who sell sex prefer to be called xiaojie to sex worker (with the result that non-sexworking misses don’t want to be called that anymore). Ding Yu, sociologist, talks about why:

Many academics feel that it’s important to respect this community by using a term that classifies what they do as a profession. But in fact many xiaojie don’t really understand or like this name because they feel the term emphasizes sex. The term “sex worker” reduces all their work to sex, which doesn’t reflect the reality of what they do. It doesn’t accurately represent the diverse forms of emotional work and entertainment that they’re engaged in; rather, it highlights the one part that’s stigmatized.

There’s an important class dimension. As migrants coming from the country to the city, they want to be part of this modern, developed world. They want to shed the kind of coarseness that’s associated with the countryside. Most ‘xiaojie’ are very well-informed about the conditions of factory work, and they know they’re not interested. They know other women from their hometowns who are factory laborers, and there are plenty of media reports that show how it is tedious, repetitive, and arduous, how the worker is treated like a machine. They know you’re stuck in dorm accommodation, far from the city center, producing luxury items you can’t afford to buy yourself. They know you are outside the modernity and development as a handmaiden to it. Other options, such as being a waitress or nanny or shop assistant — these positions generally see lower income and worse working conditions than being a xiaojie, which is thus not a particularly poor option.

In The Three-Headed Dog several migrants are selling sex. Marina lives and works in flats with other women and a manager but decides to go onto the club circuit. Promise sells in the street. Eddy is keeping company with a tourist. Isabel tried prostitution and prefers being a cleaner. The detective, Félix, once worked in spas. None call themselves or the work by a professional word. Of course, some activists think this is a problem, that there’d be more chance of successful organising if more women were willing to stand up and call themselves by the term that now sounds more like a worker title than other options. This is possible. The catch is in the stigma.

In The Three-Headed Dog several migrants are selling sex. Marina lives and works in flats with other women and a manager but decides to go onto the club circuit. Promise sells in the street. Eddy is keeping company with a tourist. Isabel tried prostitution and prefers being a cleaner. The detective, Félix, once worked in spas. None call themselves or the work by a professional word. Of course, some activists think this is a problem, that there’d be more chance of successful organising if more women were willing to stand up and call themselves by the term that now sounds more like a worker title than other options. This is possible. The catch is in the stigma.

-Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist