I rarely comment on news stories immediately and certainly not when I first need to understand a long legal text. Now I have digested the Ontario Court of Appeal’s decision to uphold the 2010 decision of Superior Court Judge Susan Himel. Representatives of the government appealed her decision last June, and it has taken all this time for the Court of Appeal to make their own decision, which upholds Himel’s only in part. All five judges did agree with Himel that key prohibitions should be struck from prostitution law: operating a brothel, working together with others and the old idea of ‘living off’ someone else’s sex work (except in genuinely coercive situations). But the court didn’t uphold one of Himel’s decisions, to allow solicitation – or ‘communication’ – in the street. This is a backward step.

I rarely comment on news stories immediately and certainly not when I first need to understand a long legal text. Now I have digested the Ontario Court of Appeal’s decision to uphold the 2010 decision of Superior Court Judge Susan Himel. Representatives of the government appealed her decision last June, and it has taken all this time for the Court of Appeal to make their own decision, which upholds Himel’s only in part. All five judges did agree with Himel that key prohibitions should be struck from prostitution law: operating a brothel, working together with others and the old idea of ‘living off’ someone else’s sex work (except in genuinely coercive situations). But the court didn’t uphold one of Himel’s decisions, to allow solicitation – or ‘communication’ – in the street. This is a backward step.

Canadian law before Himel was typical in allowing the sale of sex but surrounding the act with prohibitions, making it easy for workers to be arrested and harassed by police (as I discussed the other day in reference to London and the Olympic Games).

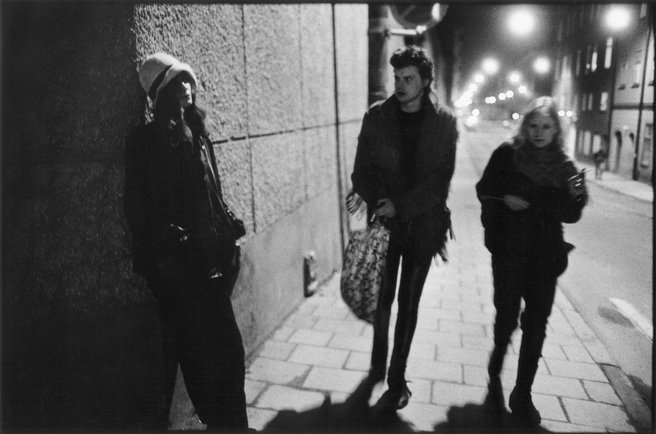

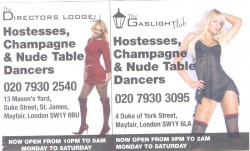

The recent decision removing obstructions from the act of selling sex in indoors, organised places, but not outdoors, is just what many business owners want and some patriarchally-inclined commentators recommend, the argument being that street prostitution is too much of a nuisance in neighbourhoods where it happens, and is overly associated with drug use and violence. This special treatment shows class, race, ethnicity, age and gender-identity bias, specially penalising those who already suffer worse marginalisation. These cards for a Mayfair venue show the image businesses love to project.

The recent decision removing obstructions from the act of selling sex in indoors, organised places, but not outdoors, is just what many business owners want and some patriarchally-inclined commentators recommend, the argument being that street prostitution is too much of a nuisance in neighbourhoods where it happens, and is overly associated with drug use and violence. This special treatment shows class, race, ethnicity, age and gender-identity bias, specially penalising those who already suffer worse marginalisation. These cards for a Mayfair venue show the image businesses love to project.

The court reasoned that if sex work is made legal in businesses and groups indoors, street workers can move inside – which the judges must know isn’t true even if they don’t admit it. Many street workers won’t be able to pass the hiring process; for instance, if employers want the prettiest people by mainstream standards, the youngest-looking people, the stereotypically feminine-looking people, those that don’t use drugs or whatever other prejudice they have. And to work in a group without such a boss requires belonging to a social network where at least one person has the organisational skills to set the group up, which also excludes many.

The court reasoned that if sex work is made legal in businesses and groups indoors, street workers can move inside – which the judges must know isn’t true even if they don’t admit it. Many street workers won’t be able to pass the hiring process; for instance, if employers want the prettiest people by mainstream standards, the youngest-looking people, the stereotypically feminine-looking people, those that don’t use drugs or whatever other prejudice they have. And to work in a group without such a boss requires belonging to a social network where at least one person has the organisational skills to set the group up, which also excludes many.

Quantitatively street prostitution occupies a minor position within the sex industry; researchers everywhere have been estimating it’s not greater than 10% of the whole for decades. But that doesn’t mean it is dying out: some people prefer the flexibility of working in the street and others fall into it as a way to survive. But is there a right to sell in the street? Urban planners, upwardly mobile home owners, politicians and numerous others think there is not; they want inner cities to look more middle-class. Those who spend time with street sex workers sometimes wind up as abolitionists and sometimes as proponents of harm reduction. Tolerance zones for street-walking are proposed and opposed constantly, everywhere.

Quantitatively street prostitution occupies a minor position within the sex industry; researchers everywhere have been estimating it’s not greater than 10% of the whole for decades. But that doesn’t mean it is dying out: some people prefer the flexibility of working in the street and others fall into it as a way to survive. But is there a right to sell in the street? Urban planners, upwardly mobile home owners, politicians and numerous others think there is not; they want inner cities to look more middle-class. Those who spend time with street sex workers sometimes wind up as abolitionists and sometimes as proponents of harm reduction. Tolerance zones for street-walking are proposed and opposed constantly, everywhere.

The Court of Appeal judges were split on this issue: the majority (three) saying soliciting should not be allowed and the minority (two) saying it should. Meanwhile, sex workers are in the uncomfortable position of wanting to celebrate, but that reaction looks insensitive towards those who work in the street. In the movement for sex workers’ rights, solidarity between different sorts of workers is highly valued and divisiveness not appreciated. Both sides of the case are likely to appeal to the Supreme Court – so onward and upward.

Thanks to John Lowman for help wading through the legal texts.

Other links of interest:

Katrina Pacey of Pivot Legal Society

BC sex workers prepared to keep challening

Himel on the ideological nonsense spouted by abolitionists

–Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist

Laura,

Interesting and thought-provoking article. Actually, New Zealand found exactly the same with its own decriminalisation laws. The hope was that if off-street sex work was decriminalised, especially through the establishment of SOOBS, street sex workers would leave the streets and work off street. This, as the legislators and a subsequent report admitted, did not happen. However, what the subsequent report also showed is that the number of street workers did not seem to increase (and neither did it seem to off street either). Moreover, as you allude to here, the stereotype of the ageing drug-addicted street sex worker with a chaotic lifestyle might have been applicable for some street workers, but for a significant minority, at least, they simply preferred the ambience and flexibility provided by the street.

It will be interesting to see where this goes in Ontario and also the impact it has both on other states and the federal level, given the zero tolerance attitude of the Harper government, its generally Christian Conservative outlook and strong antipathy towards evidence-based research.

Åolicymakers use what they think is logic and common sense to predict what people will do in the face of a law, and this is the result. Actually talking with people who work in streets or parks in any country you like would have educated these people very quickly. I know quite middle-class sex workers who prefer working outdoors, or using their cars.

Pingback: [BLOG] Some Tuesday links « A Bit More Detail

Prostitution Is A Legal Occupation In Germany, Greece And Turkey. What Are The Legal Implications?