We hear most about the big moments in sex workers’ rights movements – court decisions, parliamentary reports, conferences, public protests. But many groups engage in negotiations behind the scenes, with business managers, local politicians and sometimes with their local police.

We hear most about the big moments in sex workers’ rights movements – court decisions, parliamentary reports, conferences, public protests. But many groups engage in negotiations behind the scenes, with business managers, local politicians and sometimes with their local police.

The other day in a facebook conversation about whether to negotiate with municipal authorities and police, Sue Davis posted a timeline about sex workers’ efforts and achievements in Vancouver, British Columbia. She supplied links to the reports produced, and I’m reproducing her words here without interruption.

NB: The Downtown Eastside of Vancouver was a serial killer’s hunting-ground for victims during a long period when police egregiously neglected the area, not caring what was happening to disappearing women – poor women selling sex in the street. References here are to ‘Missing Women’.

In the words of Susan Naomi Davis:

In Vancouver it started with cooperative development: Cooperative Development Exploration Report

In Vancouver it started with cooperative development: Cooperative Development Exploration Report

By Sue Davis and Raven Bowen

With Support of the BC Coalition of Experiential Women

February 2007

Then there was labor rights exploration:

SEX INDUSTRYSafety and Stabilization

Susan Davis and Raven Bowen

BC Coalition of Experiential Communities

2007

From there we did some strategic planning:

From there we did some strategic planning:

Leading the Way:Strategic Planning Toward Sex WorkerCooperative Development

January 2008

At this point we received a little funding to develop Occupational Health and Safety materials:

Trade SecretsOccupational Health and Safety Guidelines for Sex Industry Workers

Trade Secrets for sex industry workers

Trade Secrets for sex industry workers

So then we worked to figure out how to implement the cooperative brothel and Occupational Health and Safety. That work resulted in:

Opening the Doors- Final Report

BC Coalition of Experiential Communities 2011

During this time we had also been working on issues related to exclusion by victims services etc and had been attending the Police Board as a delegation to ask for an amnesty to be able to open the coop brothel/safe work site, or, as it was lovingly called at the time, “the safe erection site”. We were invited to the Diversity Advisory Committee with the Vancouver Police Department (VPD), a committee working on issues related to policing in marginalized communities. There were lots of other groups represented there, but it became clear quickly that sex workers needed their own group, as our issues were taking over every meeting.

So the Sex Industry Worker Safety Action Group was created and included sex workers groups and the VPD working together to try to address issues of policing. that work resulted in the VPD lowest-level-of-enforcement policy:

So the Sex Industry Worker Safety Action Group was created and included sex workers groups and the VPD working together to try to address issues of policing. that work resulted in the VPD lowest-level-of-enforcement policy:

Vancouver Police Department

SEX WORK ENFORCEMENT GUIDELINES

Adopted January 2013

With the assistance of:

WISH, PIVOT, BC Coalition of Experiential Communities, PEERS and PACE

At the same time the Missing Women’s Commissions was underway and had released it’s recommendation:

FORSAKEN – The Report of the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry

VOLUME III

Gone, but not Forgotten:

Building the Women’s Legacy of Safety Together

November 15, 2012

This report contained many of the recommendations submitted by the BCCEC based on work we had done under the leadership of Raven Bowen – a visionary – and included policing recommendations as well as City of Vancouver inspections and housing and other responses

This report contained many of the recommendations submitted by the BCCEC based on work we had done under the leadership of Raven Bowen – a visionary – and included policing recommendations as well as City of Vancouver inspections and housing and other responses

A task force was struck and a policy similar to the VPD policy emerged and stated that sex work is explicitly NOT a by-law violation:

City of VancouverSex Work Response Guidelines

A balanced approach to safety, health and well-being for sex workers

and neighbourhoods impacted by sex work

September 2015

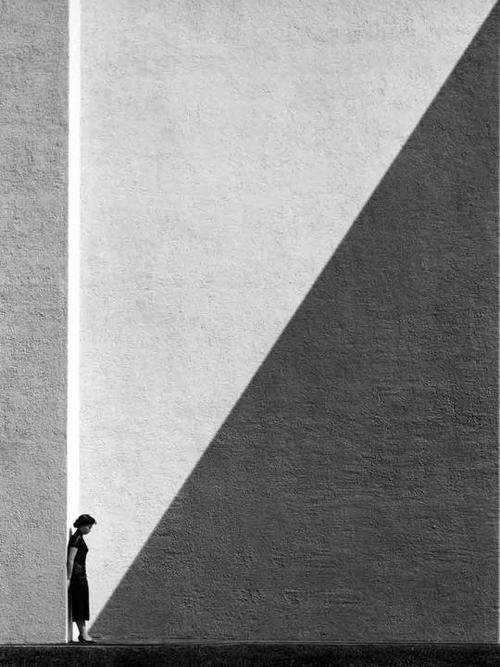

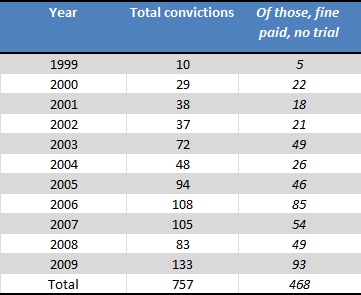

The point of all this is that we achieved the most change via local police and inspections agencies rather than trying to create change at the national level. Locally, after Canada’s worst serial killer. people were motivated by guilt for bad policies which had delivered sex workers into the hands of that animal – who we never name, fuck that guy – it is the legacy of the women who died. They were the reason that we were able to move things forward here. These relationships with city staff and police need constant care and oversight by sex workers. We have seen several incidents where city staff and police reverted to the practices of the past and have had to re-educate them about why the policies were created in the first place.

We continue to work with police and city staff in an ongoing way. There has not been a massage-parlor raid in years, no arrests of sex workers in years and no murders of sex workers as a result of their work in 11 years – (one sex worker stabbed another sex worker in an argument over a cigarette and she died). Overall I would say that it was well worth the blood, sweat and tears. I have been in yelling matches with police officers during these meetings – nose-to-nose screaming – to see the outcomes emerging in Vancouver.

Not all sex worker groups here agree with working with police and some refuse to work with them at all. Since sex workers have expressed to us that their number-one concern is arrest and enforcement, we continue to follow their direction and engage with police to ensure freedom from enforcement here.

We engaged with our local politicians and any entities whose work impacted the safety of community and continue to do so now. We have recently become organizational partners with the local community policing office and believe there is real potential to decentralize policing via the 9 community-policing offices in the city. Groups representing people who experience negative impacts of police action could join the boards of community policing centers, and we could see a venue for direct change in policing practices.

So i know this was long…but so was the journey to get here…it was not easy, it was emotional and exhausting… it is emotional and exhausting…. but now 45 police services and the e-division of the RCMP have all signed onto lowest-level-of-enforcement across our province. We hope that when the federal government finally review the current legal framework [anti-sexbuying law], the fact that police are not using these laws and do not support them will have some impact.

You can copy and share as you like and please feel free to use, share, critique… We love to hear what people think and to answer questions! You may write to susan dot 1968 at hotmail dot com.

§

About Sue Davis in 2009: Sex workers and researchers defend clients in Vancouver

Sue and I met in person in 2011: Sex at the Margins in Vancouver: sex trafficking, migrant sex work and rescue

And from me about Canada in the past:

All the scary things a little decriminalisation of prostitution might cause in Canada Nov 2010

Bedford v Canada: Report from the courtroom on prostitution law and sex work June 2011

Remembering Judge Himel: Bold assertions and inflammatory language not useful to the court June 2013

Judge dismisses academic claim to sex-trafficking expertise Sept 2013

§

–Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist