The new Trafficking in Persons Report (TIP) has once again been issued by the US government. I went back to a piece I wrote about this annual shameful phenomenon in 2007, when the Philadelphia Inquirer rang to solicit a piece on the subject. The only thing different now concerns the perceptions of US citizens outside the US: abysmal and worsening then, slightly better now with the election of Obama. It remains to be seen whether this new administration will be able to see and grapple with the imperialism inherent in the TIP, however. Everything else I said two years ago I stand by today. The paper didn’t change my text but did change the title badly (my original appears first below).

The new Trafficking in Persons Report (TIP) has once again been issued by the US government. I went back to a piece I wrote about this annual shameful phenomenon in 2007, when the Philadelphia Inquirer rang to solicit a piece on the subject. The only thing different now concerns the perceptions of US citizens outside the US: abysmal and worsening then, slightly better now with the election of Obama. It remains to be seen whether this new administration will be able to see and grapple with the imperialism inherent in the TIP, however. Everything else I said two years ago I stand by today. The paper didn’t change my text but did change the title badly (my original appears first below).

What’s Wrong With the ‘Trafficking’ Crusade?

Well-meaning interference?

The Philadelphia Inquirer Sunday 1 July 2007

Op-Ed page

Laura Agustín

It’s the season when the United States issues its annual Trafficking in Persons Report (TIP). Having named sexual slavery as a particular evil to be eradicated, the United States grades other countries on how they are doing.

On the one hand, it sounds like an obvious way to do good: Describe the ghastly conditions you as a rich outsider observe in poor countries. Focus on places where sex is sold. Say all women found were kidnapped virgins and are now enslaved; announce to the world that you will liberate them. Organize raids. Denounce anyone who objects – even if their objection is that you are intervening in their country’s internal affairs. Ignore victims who resist rescue. Use lurid language and talk continuously about the most sensational and terrible cases. Justify your actions as a manifestation of faith, as though it exists only for you. Mutter about “organized crime.”

This is also the season when tourists leave the United States en masse to visit the rest of the world, where their country is more disliked all the time. People who used to say: “It’s just the president [or the government], ordinary Americans are all right,” now say it less often. Ignorant, destructive interventions into other countries’ business have been going on too long.

Grading everyone else on moral grounds is highly offensive, particularly when such grades are accompanied by threats of punishment if the line isn’t toed. It’s distressing to witness the deterioration of what good will is left toward this country since the post-2001 wars were initiated and campaigns intensified that presume the United States Always Knows Best.

For crusading politicians and religious leaders, a rhetoric of moral indignation is effective in uniting constituents and diverting the collective gaze away from familiar problems at home. So the culprits, those who get bad grades in the TIP, live far away from U.S. culture, which is assumed to be better. Intransigent local troubles – prisons overflowing with African Americans, millions of children malnourished – are swept aside in the call to clean up other people’s countries.

This moral indignation emanates from people who live comfortably, who are not wondering where their next meal will come from or how to pay doctors’ bills. These moral entrepreneurs do not have to choose between being a live-in maid, with no privacy or free time and unable to save money because the pay is so bad, and selling sex, which pays so well that you have time to spend with your children or read a book, money to buy education or a phone.

It is easy to haul out sensationalistic language (sex slavery, child prostitution), but it is much harder to sort out the real victims from the more routinely disadvantaged and trying-to-get-ahead. Those who know intimately the problems of the poor in their own cultures rarely deny that they can decide to leave home and pay others to help them travel and find work, in sex or in any other trade.

“But sex for money is disgusting and degrading; no one should have to do it.” And should anyone have to clean toilets all day? Risk being maimed in unsafe fireworks factories? Should children have to spend their lives in lightless tunnels of mines, or women have to remain married to men who are cruel to them? The world is full of things we wish we could eradicate – but isn’t starvation the first of them? Why is there no equivalent moral furor over hideous poverty? Are we meant to believe that sex without love is worse than military violence? All over the world, selling sex pays better than most jobs readily available to women, and many do not believe it is the worst possible experience they can have.

What’s questionable about the TIP is not the defense of children or anyone else against true violence – it’s one government’s assumption that it has the right to judge everyone else and apply a draconian definition of exploitation that does not ask people whether and how they would like to change their lives. Questionable is the focus on the photogenic, cowboy moment of rushing in to rescue slaves, with no interest in what will follow.

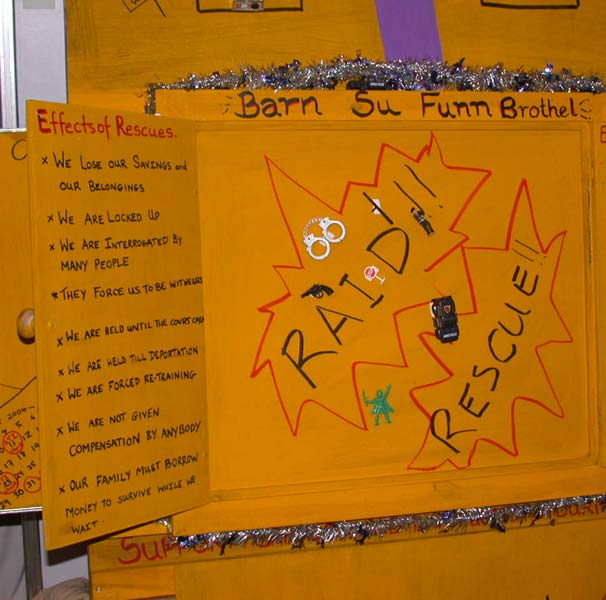

Victims are “protected” rather than granted autonomy. At the Empower Center in Chiang Mai, Thailand, signs written by migrant women “rescued from” selling sex include: “We lose our savings and belongings”; We are locked up”; “We are held till deporation”; “We are interrogated by many people”; “Our family must borrow money to survive while we wait.”

From the standpoint of social science, the TIP is gravely faulty. It never explains how data were gathered and compared across so many languages and cultures, or who did it exactly under what circumstances. A raft of other research shows enormous diversity among people who sell sex, and a wide variety of experiences in the sex industry among both migrants and people who stay at home. Studies show that the worst kind of trafficking can happen to people doing other kinds of jobs – and to men. Women all over the world, including the poorest, repudiate being characterized as above all sexually vulnerable.

In assuming its creators’ moral values are or should be universal, the TIP ignores local cultures and the complexities of human desires and functions – yet another reason tourists from the United States will be less welcome everywhere this summer.