I first published this piece in 2002, but its message is truer than ever as rescue operations presently receive large amounts of funding in many parts of the world. I am republishing it here since so many new people have entered a research field and joined social movements to save people without understanding how it all started – in conversations about women and travel. Note: Since all brothels are ‘legal’ in Sydney I shouldn’t have used the word, which implies there are also ‘illegal’ brothels. Thanks to Scarlet Alliance for the correction.

I first published this piece in 2002, but its message is truer than ever as rescue operations presently receive large amounts of funding in many parts of the world. I am republishing it here since so many new people have entered a research field and joined social movements to save people without understanding how it all started – in conversations about women and travel. Note: Since all brothels are ‘legal’ in Sydney I shouldn’t have used the word, which implies there are also ‘illegal’ brothels. Thanks to Scarlet Alliance for the correction.

The (Crying) Need for Different Kinds of Research

Laura Agustín, June 2002, Research for Sex Work 5, 30-32. pdf

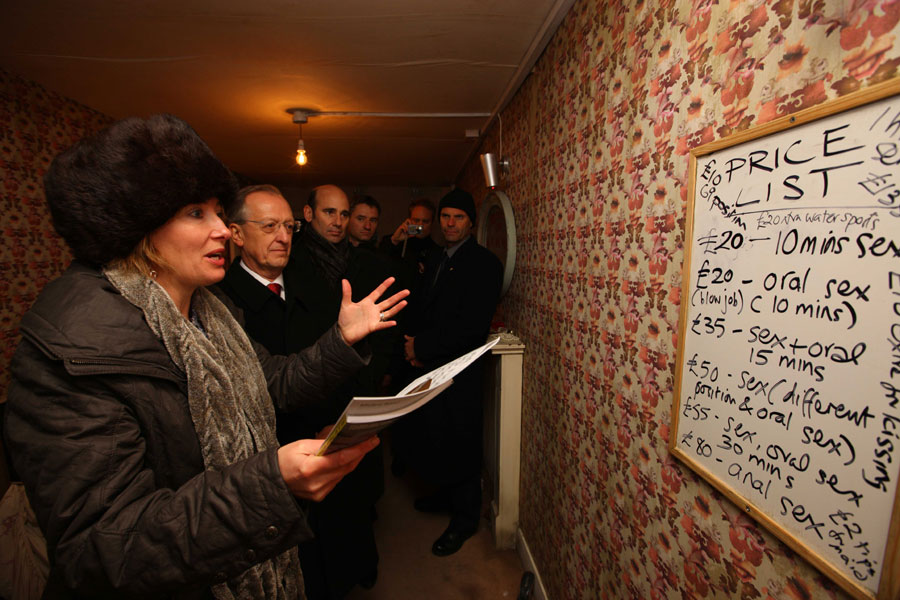

In October 2001, while on a trip to Australia and Thailand, I met five Latin American women with some connection to the sex industry: the owner of a (legal) brothel and two migrants working for her in Sydney, and two women in a detention centre for illegal immigrants in Bangkok. These five women were from Peru, Colombia and Venezuela; they were from different strata of society; they were very different ages. They also all had quite different stories to tell.

The brothel owner now had permanent residence in Australia. Her migrant workers had come on visas to study English which gave them the right to work, but getting the visa had required paying for the entire eight-month course in advance, which meant acquiring large debts. The Madam was very affectionate with them but also very controlling; they lived in her house and travelled with her to work. She was teaching them the business; the outreach workers from a local project did not speak Spanish.

Of the two women detained in Bangkok, one had been stopped in the Tokyo airport with a false visa for Japan. She had been invited by her sister, who had been an illegal sex worker but now was an illegal vendor within the milieux. The woman had been deported to the last stage of her journey, Bangkok; there she had been in jail for a year before being sent to the detention centre. The second detained woman had been caught on-camera in a robbery being carried out by her boyfriend and others in Bangkok, after travelling around with them in Hong Kong and Singapore; she had just completed a three-year jail sentence before being sent to the centre (and she also had completely false papers, including a change of nationality).

Both detained women were waiting for someone to pay their plane fare home, but no one was offering to do this, since their degree of complicity in their situations disqualified them from aid to victims of trafficking, and not all Latin American countries maintain embassies in Thailand. Only one person from local NGOs visiting the detention centre spoke Spanish.

How can we understand these stories?

Given the very different stories these women have to tell, labelling them either ‘migrant sex workers’ or ‘victims of trafficking’ is incorrect and unhelpful to an understanding of why and how they have arrived at their present situations. The placing of labels is largely a subjective judgement dependent on the researcher of the moment and is not the way women talk about themselves, something like the attempt to make complicated subjects fit into a pre-printed form. The following descriptions illustrate this complexity.

While the two new migrants in Sydney seemed accepting of the work they had just begun doing, there was clearly ambiguity about the significance of the language course on which their visas were based, and their debts did not leave them much choice about what jobs to do.

The migrant to Japan believed she would not have to sell sex, but her own family had been involved in getting her the false papers, and she was suffering considerable guilt and anguish. The woman caught in the robbery seemed to have sold sex during her travels, but without any particular intention or destination being involved, nor did she give the matter much importance. The total number of outsiders implicated in their journeys and their jobs was large; nationalities mentioned were Pakistani, Turkish and Mexican. The need for research to understand how all these connections happen is urgent, but funders are unlikely to finance research that does not fit into one of the currently acceptable theoretical frameworks: ‘AIDS prevention’, ‘violence against women’ or ‘trafficking’.

These frameworks reflect particular political concerns arising in the context of ‘globalisation’, and they are understandable. Elements of the stories of people such as those I have described may share features with typical discourses on ‘trafficking’, ‘violence against women’ and ‘AIDS’, but these are prejudiced, moralistic frameworks that begin from a political position and are not open to results that do not fit (for example, a woman who admits that she knew she would be doing sex work abroad and willingly paid someone to falsify papers for her).

The desires of young people to travel, see the world, make a lot of money and not pay much attention to the kind of jobs they do along the way are not acceptable to researchers that begin from moral positions; neither are the statements by professional sex workers that they choose and prefer the work they do. Yet ethical research simply may not depart from the claim that the subjects investigated do not know their own minds.

Why do we do research, anyway?

A theoretical framework refers to the overall idea that motivates services or research projects. For service projects with sex workers this framework might be a religious mission to help people in danger, a medical concept of reducing harm or a vision of solidarity or social justice. Most projects with sex workers focus on providing services, not doing research, though often the line between them is not easy to draw.

Service projects accumulate a lot of information over time, but it seems as though the only thing governments want to know about is people’s nationalities, how old they are, when they first had sex and whether they know what a condom is. Many NGO and outreach workers would like to publish other kinds of information, research other kinds of things. But where, how? If their research proposal does not reflect one of the existing research frameworks regarding migrant prostitution – ‘AIDS prevention’, ‘trafficking’ or ‘violence against women’ – it will be hard if not impossible to find funding.

Some of my own research concerns people who work with sex workers, like the people who read this publication. Continue reading

I am in Porto, Portugal’s second-largest city, to give a plenary talk at the opening of a conference on harm reduction called

I am in Porto, Portugal’s second-largest city, to give a plenary talk at the opening of a conference on harm reduction called