Tijuana is a city in the north of the state of Baja California in Mexico, close to the San Isidro Land Port of Entry, where wikipedia says 20,000 pedestrians cross northwards daily. This is the route chosen by most of those called the Migrant Caravan, Central Americans who have travelled together through Mexico to reach the border and request asylum in the USA. Dina Francesca Haynes, a law professor just returned from four days’ work amongst migrants on the Mexican side, has given permission to reproduce her facebook report, including the photos she took.

Tijuana is a city in the north of the state of Baja California in Mexico, close to the San Isidro Land Port of Entry, where wikipedia says 20,000 pedestrians cross northwards daily. This is the route chosen by most of those called the Migrant Caravan, Central Americans who have travelled together through Mexico to reach the border and request asylum in the USA. Dina Francesca Haynes, a law professor just returned from four days’ work amongst migrants on the Mexican side, has given permission to reproduce her facebook report, including the photos she took.

Field log, leaving Tijuana, 4 December 2018

I am still a bit overwhelmed and my thoughts are not yet settled, but here are some impressions.

People from all over the world are suffering. Some have pinned their dreams on the United States, and my job, as I see it, includes giving them a realistic understanding of what they are about to encounter, so that they can make an informed decision before they decide to cross into the US. What they are about to face is detention often in hostile conditions, in facilities run by uncaring and unprofessional private prisons, intent on making already miserable people more miserable, for profit. A Russian roulette of asylum officers and immigration judges. Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breath free is but a bitter memory.

The US can certainly absorb these people. This group of 5-7 thousand currently in Tijuana, with more on the Mexican side of other ports of entry, is an entirely political problem. An unlawfully executed political problem. Far more people have come each year for decades. The problem is the unlawful bottleneck that the US government has imposed. The law states that any person may present themselves at a port of entry and request (the opportunity to apply for) asylum. The US is imposing a procedural limit on the number of people (without visas) who may cross to seek asylum, and the Mexican government, who also limit the number of people who can start to cross, based on the daily, seemingly arbitrary decision of the US, is complicit. Each person is designated a number. Some have it written on the inside of their forearm in sharpie. I don’t have to tell you what that invokes. Today, for example, 30 people were permitted to cross. Sunday, none were. Possibly as retaliation for actions they didn’t like, as a show of power. The rest wait in unsafe conditions for weeks to months longer. Each day hundreds trek to the border to see if their number is called. The atmosphere where people wait is ripe with adrenaline-nerves and fear and hope.

Today I helped three orphans traveling alone from Sierra Leone, Cameroon and Guinea Conakry. They had been on the road for 3 months, travelling from South Africa to Brazil to Ecuador to Panama where they walked across the country. They are children. They arrived in Mexico and tried to find other Africans. One older African offered to take them in. Two other older Africans, one only 18 herself and another studying to be a minister, had offered to help lend them some money. To do this, they had arranged to wire money to the Mexican citizens working in the store below where they were staying. You might have guessed the end of this story already – the wired money was received, but not passed along to the intended recipient. I gave legal advice to a girl the same age as my daughter who had been raped by police in her country that is descending into chaos. I gave legal advice to a boy escaping his uncle’s demand that he become a child laborer, enslaved to another for life. I walked a group of 15 people to find some food to eat. They hadn’t eaten a real meal for days. I gave one of them my tennis shoes.

On Friday, I helped a woman from Guatemala and her two children. She was so astute and caring and determined that, in addition to everything else she was dealing with, she asked if I could help her find a therapist to speak to her children who were traumatized. So I did, because there was a therapist coming to volunteer.

Today, three volunteer pastors from different churches arrived to marry couples afraid of being separated when they crossed, most same sex couples.

There is a lot of heart here. The people coming to volunteer gain nothing except love and grace. They expend a lot, emotionally, physically and financially. There are people helping to cook and serve food to the hungry. People unpacking clothes that have been donated. People calling and paying for taxis to get people to and from safe houses and urgent appointments. There are people monitoring what the police and border patrol are doing and the myriad ways they are violating the law. People giving money to those who have none. There are translators and students and doctors. People giving.

There is also chaos and bottomless need and people operating in emergency mode, responding and putting out fires and having no time to plan or think about how to best proceed or coordinate. There are muddy fields where people have been living and are getting sick. One little girl asked if she would be taken away from her mother. She hugged me when she said goodbye, and then thanked me in English. So much heart and fortitude expended by people who travelled months to try to get to the US to seek asylum. So much heard and grace expended by volunteers trying to serve them, as we all work together in a building with an open sewer outside and a space barely fit to serve a few, let alone masses of need.

We US citizens are living through a humanitarian crisis that we have allowed our own government to create. Many of us are allowing ourselves to be blind to it, because it is horrible to think about. Because we have exported the locus of the tragedies we have created. But that doesn’t change the fact that is happening and that we are responsible, because our government is perpetrating this by violating international law, and its own domestic law for no gain. We gain nothing by limiting the number of asylum seekers who enter. And we lose nothing by letting them apply. If we had directed the funds expended on sending 5600 troops to the border to this problem, instead, it could have been solved 10 times over, weeks ago.

We have the capacity to absorb these people with little or no negative consequence. We are choosing not to, because our government has decided to demonize the smallest annual number of asylum seekers in years. They deserve so, so much more. — Dina Francesca Haynes, Professor of Law

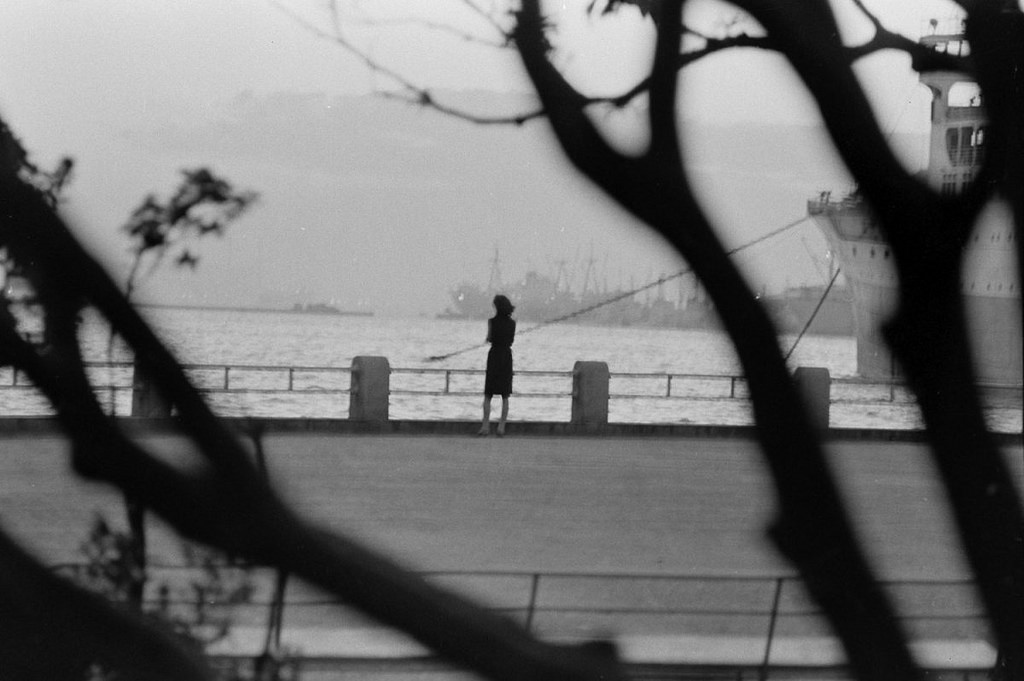

I’ve lived many such complicated and long-drawn-out moments on different borders myself, including a job 25 years ago at the other end of this border at Matamoros/Brownsville. Dina’s two gloomy brown photos look to me like the detention centers I’ve seen in Texas, but Dina says they are part of the architecture of the border crossing at San Ysidro. The resemblance is clearly not coincidental.

Though Tijuana/San Ysidro don’t look like Calais and other migrant camps near the Channel Tunnel, they don’t look that unlike, either. The longer so many people have to wait, the worse things become, in a myriad of ways.

For some of my writings about borders see Border Thinking and Segregation, colonialism and unfreedom at the border . They were prompted by airport borders into the UK but I’ve had these experiences in many countries of the world.

I’ve tweeted about this migration caravan (@LauraAgustin) and surely will again.

—Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist