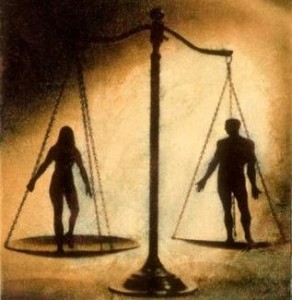

I feel like the veteran of a long, drawn-out war. I first knew it as the War Between the Sexes (back when I thought there were only two). Now it feels like a World Gender War, in which a small number of women endeavour to bring all men and all disagreeing women to their knees (the existence of other sexes or gender identities is routinely dismissed). In this war, masculinity is equated with patriarchy (a strategy of domination), the penis becomes a weapon of mass destruction and the vagina is an open, constantly violated wound.

I feel like the veteran of a long, drawn-out war. I first knew it as the War Between the Sexes (back when I thought there were only two). Now it feels like a World Gender War, in which a small number of women endeavour to bring all men and all disagreeing women to their knees (the existence of other sexes or gender identities is routinely dismissed). In this war, masculinity is equated with patriarchy (a strategy of domination), the penis becomes a weapon of mass destruction and the vagina is an open, constantly violated wound.

Sexual acts involving women and men are the major battlefield of this war, outperforming unequal job opportunities and wages, unpaid housekeeping and caring labour, inadequate health care, sexist stigmas and poverty itself as crimes against women. For crusaders, the male body is the problem of patriarchy and sexual relationships over-riding concerns. Particular sexual relationships are said to be correct and a wide range of others, where power is defined as ‘unbalanced’, are the target of eradication campaigns, in Europe as well as the US. Pornography, prostitution and rape at the top of the list, but surrogate motherhood and transsexuality are not exempt.

Nowadays, the 1950s are dismissed as a Dark Age for women ejected from wartime jobs into neurotic house-cleaning, child-rearing and the vaginal orgasm. I remember that period and wouldn’t want to bring it back, but a lot of what I hear now is not better. 1960s women’s liberation was about women acknowledging and standing up for their desires and ambitions. Legislative and wider political proposals emerged, but the foundation was about individual women understanding their oppression and learning how to express their own selves, whatever those were. The initial stage was not about political correctness or ideology, and it felt liberating, all right.

For some of the 1970s, I lived in San Francisco, and I recall the day I noticed a shop had opened near my house at 22nd Street and Guerrero. The window displayed dark metallic objects I couldn’t identify, so I went through the door to a space no bigger than some closets where a woman explained the mysteries of antique vibrating objects. Although some now laugh at or dismiss the phrase sexual liberation (pace Foucault), it did not sound funny then. Learning about sex – the acts of sex – was important at a time when almost no information was available at all. The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm was a breakthrough essay, and then others said it wasn’t entirely a myth, and so it went, constant discoveries that every sort of sexual configuration and activity was feasible and satisfying for someone. What a deliverance: Now there would be no need to live up to anyone else’s idea of Good Sex.

The names Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon crop up these days as people struggle to understand the reductionist, unforgiving ideas associated with a particular version of feminism that claims itself to be the One True Faith. The first US Take Back the Night march, where Dworkin spoke, was held in San Francisco in 1978, but even though I was living in the city I didn’t know anyone who went. I wouldn’t have felt opposed but rather that my concerns were different, and I wouldn’t have understood why the march was going through red-light areas: the link between rape and the sex industry was not apparent to my own young feminist self.

I often meet women annoyed that the term radical feminist should go to mean-spirited, authoritarian and apparently sex-hating folk. I don’t blame them for wanting to reclaim radical, since a stream of thought that once proposed revolution now wants to make us obey a narrow set of sexual rules – like in the 1950s and other repressive eras. This is fundamentalist ideology, a claim that there is only one truth about sex and women. The opposite of grassroots politics, this fundamentalism is transmitted by an elite cadre of leaders who forbid differences of opinion. No cultural relativism or local history is permitted to interfere with simplistic, reductionist principles that are applied to all people despite what they feel themselves.

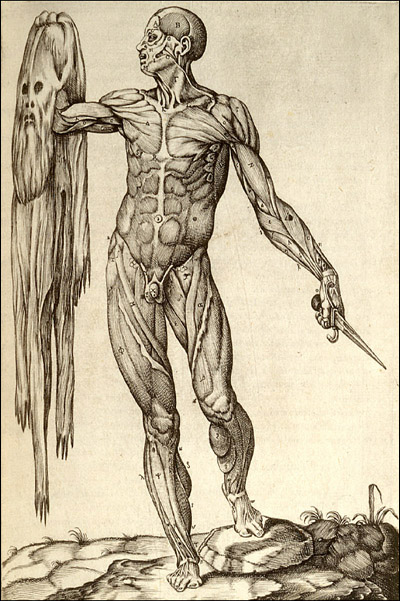

Dworkin famously likens the penis to an invading weapon in her book Intercourse. In this war zone, male sexuality is inherently violent, exploitative and imperialistic, reduced to the penis which is said to have to push past the vulva’s muscles. Male sexuality is described as a weapon of predation and violence that only criminal law and punishment can solve.This is anatomical fundamentalism, in which an erect penis is said to be capable of doing more harm than other body parts might do – a stiff tongue, hard nose, knee or finger. Vaginas are imagined as not doing anything but defencelessly wait to be invaded (amusing when one remembers the old idea of women’s dangerous, toothed vagina, not to mention spider women and other scary types). But this sort of anatomical determinism comes up in contexts far from Dworkin’s thinking; for example a recent report claimed that the way female rats curve their backs and raise their hips for sex means they are submissive. But neither physical traits nor bodily positions have inherent meanings, as any sane commentator knows.

Dworkin famously likens the penis to an invading weapon in her book Intercourse. In this war zone, male sexuality is inherently violent, exploitative and imperialistic, reduced to the penis which is said to have to push past the vulva’s muscles. Male sexuality is described as a weapon of predation and violence that only criminal law and punishment can solve.This is anatomical fundamentalism, in which an erect penis is said to be capable of doing more harm than other body parts might do – a stiff tongue, hard nose, knee or finger. Vaginas are imagined as not doing anything but defencelessly wait to be invaded (amusing when one remembers the old idea of women’s dangerous, toothed vagina, not to mention spider women and other scary types). But this sort of anatomical determinism comes up in contexts far from Dworkin’s thinking; for example a recent report claimed that the way female rats curve their backs and raise their hips for sex means they are submissive. But neither physical traits nor bodily positions have inherent meanings, as any sane commentator knows.

Movements resisting sexual repression have to contend with difficult contradictions: that men tend to be physically stronger than women, that male arousal and orgasm are more evident than female and that violence against women and sexism are still ubiquitous. Who could have predicted that my way of thinking about migration and selling sex could end up being seen as a sign of collusion with the enemy? Women like myself who were alive in the 60s are viewed as particularly sinister traitors to the fundamentalist cause, because we ought to know how things should have turned out. When I nearly ran into MacKinnon recently at a Swiss university I could imagine the potential confusion felt by people hearing us both, because, despite our similar age, our mental universes seem spectacularly opposed.

The World Gender War is most evident nowadays in campaigns to criminalise men accused of causing prostitution and human trafficking through their willingness to buy sex. Ideological crusades assuming all women want the same things include the European Women’s Lobby’s Prostitution-free Europe to Hunt Alternatives’ End Demand and Ashton Kutcher’s Real Men Don’t Buy Sex. I am accused of being a pimp or pornographer because I don’t think male sexuality per se is the problem. Instead I believe we are all engaged in a slow process of working out how to get along sexually with different sorts of equipment, different desires and different ways of going about satisfying them.

Originally published at Good Vibrations Magazine

Feminists have better sex is the latest

Feminists have better sex is the latest