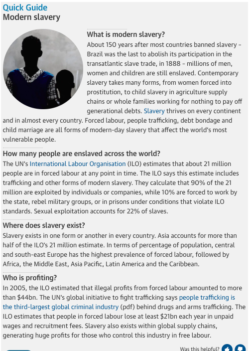

I wouldn’t have been surprised if the term migrant sex worker had died out except amongst rights-activists, given the hegemony enjoyed by reductionist trafficking narratives. When I was doing the intellectual work required to produce Sex at the Margins, I didn’t use labels for people but rather described a group of women leaving home for elsewhere and getting by cleaning houses and selling sex. Not all migrants who sell sex are women but women’s presence selling sex was what was manifestly ignored, in a way that reminded me of a lot of other ignoring I’d seen in my life. When I started there was no mention of these women anywhere in the media and then when I searched further I also found nothing in academic articles or books, even in the field of migration. Apparently they didn’t qualify as migrants, or could it be no reporter or student was interested in them as subjects of study? As time went on I understood, from reactions when I spoke about my work, that something else was going on and that au contraire everyone was really perhaps sometimes even too interested.

I wouldn’t have been surprised if the term migrant sex worker had died out except amongst rights-activists, given the hegemony enjoyed by reductionist trafficking narratives. When I was doing the intellectual work required to produce Sex at the Margins, I didn’t use labels for people but rather described a group of women leaving home for elsewhere and getting by cleaning houses and selling sex. Not all migrants who sell sex are women but women’s presence selling sex was what was manifestly ignored, in a way that reminded me of a lot of other ignoring I’d seen in my life. When I started there was no mention of these women anywhere in the media and then when I searched further I also found nothing in academic articles or books, even in the field of migration. Apparently they didn’t qualify as migrants, or could it be no reporter or student was interested in them as subjects of study? As time went on I understood, from reactions when I spoke about my work, that something else was going on and that au contraire everyone was really perhaps sometimes even too interested.

My favourite straightforward piece of early writing on migrants who sell sex is The (Crying) Need for Different Kinds of Research: Not all is trafficking and AIDS. Later on I published in academic journals, but never easily, as peer-reviewers who knew the subject could not be found in those days, and who was I supposed to be citing if no one had written yet? Who could have vouched for it except for the subjects themselves? Academic publishers consulting objectified subjects: absurd idea.

My favourite straightforward piece of early writing on migrants who sell sex is The (Crying) Need for Different Kinds of Research: Not all is trafficking and AIDS. Later on I published in academic journals, but never easily, as peer-reviewers who knew the subject could not be found in those days, and who was I supposed to be citing if no one had written yet? Who could have vouched for it except for the subjects themselves? Academic publishers consulting objectified subjects: absurd idea.

Anyway, eventually I published A Migrant World of Services: the emotional, sexual and caring services of women, 2003, and Migrants in the Mistress’s House: Other Voices in the Trafficking Debate, 2005 and, taking two and a half years to get published in a migration journal, Disappearing of a Migration Category: Migrants Who Sell Sex, 2006. Still my preference was never to label people migrant sex workers, as no one I’d ever known talked that way about themselves. They were travelling, they were working at night, they were prostitutes, they were helping families, they didn’t want to be maids.

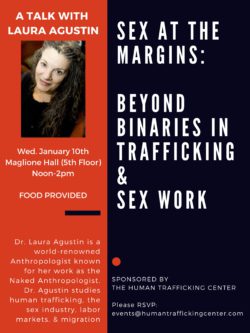

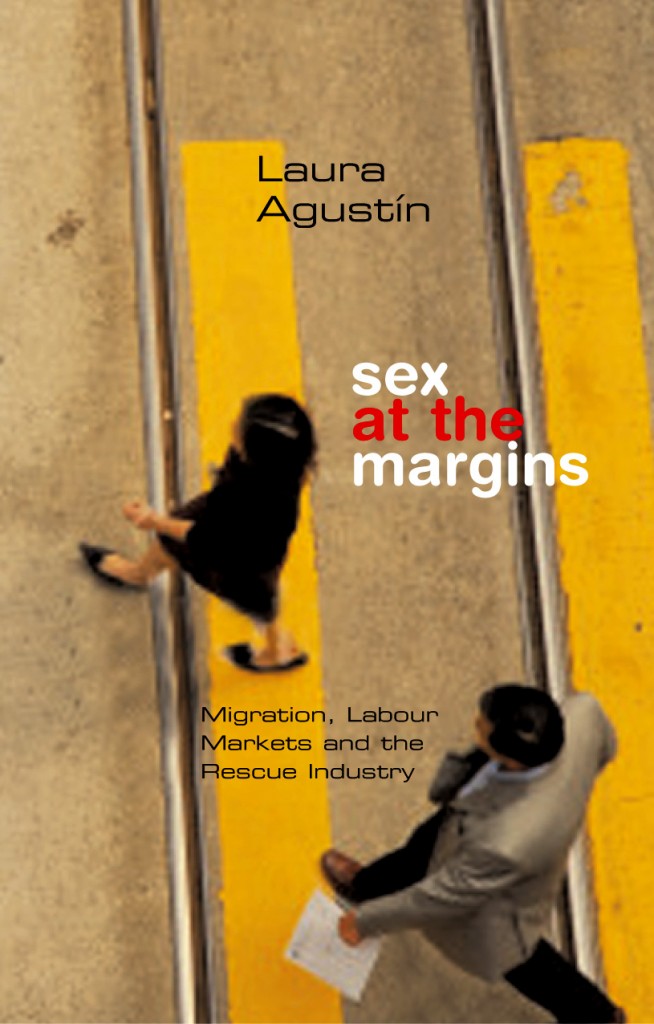

In  Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets and the Rescue Industry, published in 2007, I believe I only used the phrase migrant sex workers once:

Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets and the Rescue Industry, published in 2007, I believe I only used the phrase migrant sex workers once:

But people who desire to travel, see the world, make money and accept

whatever jobs are available along the way do not fall into neat categories: ‘victims of trafficking’, ‘migrant sex workers’, ‘forced migrants’, ‘prostituted women’. Their lives are far more complex – and interesting – than such labels imply.

Of course by writing the book I drew attention to actions and lifestyles that can add up to an identity, even if it’s only temporary and not used by subjects themselves.

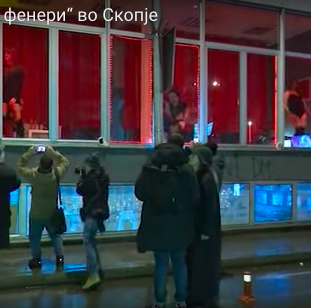

About labels and categories: You often see, in European web material, references like ‘street-based sex workers’. Sometimes that’s a covert way to say migrant sex workers, because there are always migrants selling sex on some street in European cities. Many more aren’t on the street, but only those on streets are readily identifiable by NGO workers and police, who engage in naming and counting. And then there are all the references to victims of trafficking who consider themselves to be migrants.

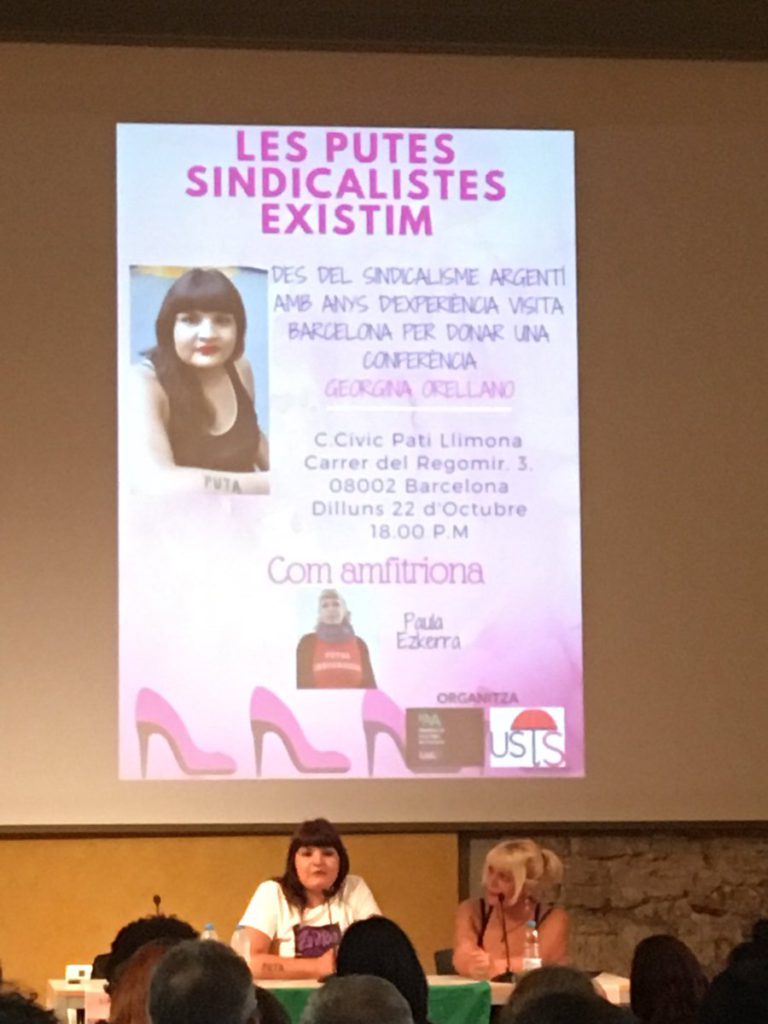

Projects with migrant sex workers are flourishing in the world of activism. Take Crossings:

Projects with migrant sex workers are flourishing in the world of activism. Take Crossings:

A sex-worker produced documentary about the poverty, criminalization, and struggle of migrant sex workers in Europe. The film features the stories of sex workers from 5 European countries, Ukraine, Norway, France, Spain, and Serbia and was collaboratively produced by sex worker organizations and the International Committee on the Rights of Sex Workers in Europe. The project was supported by the Public Health Program of the Open Society Foundations.

That’s right: George Soros’s Open Society funding supports work on migration and sex work both. Tampep (The European Network for the Promotion of Rights and

That’s right: George Soros’s Open Society funding supports work on migration and sex work both. Tampep (The European Network for the Promotion of Rights and

Health among Migrant Sex Workers) gets EU funding, because, while fanatics rant to exclude migrants absolutely, governments know how easily they get in, and you know how scary ‘threats to public health’ are. Specially sexual ones.

The term is also normalised in Canada, where Butterfly Asian and Migrant Sex Worker Support Network operates. See their report Anti-trafficking campaign harms migrant sex workers, which ends

We believe women when they tell us they are not trafficked and we believe them when they say they are. And when others like us are targeted or deported, we will not be held as complicit in violence against women because we are sex workers and refuse to be framed as victims. We do not consent to this status.

Some academics use the term, for example when demonstrating that all is not exploitation and misery when foreigner workers are concerned.

University of Otago, Christchurch releases first study of migrant sex workers: The majority of migrant sex workers in New Zealand who participated in new University of Otago research, are in safe employment situations and working to fund study or travel rather than being desperate, exploited or trafficked, the research shows.

Since the exclusion of migrant sex workers is the flaw in New Zealand’s rational prostitution law it’s logical that academics there should be using the term rather than wailing about trafficking.

I didn’t use the term migrant sex worker in The Three-Headed Dog, although numerous of the characters can be called that. It’s a novel in which people migrate to Spain and sell sex in different ways and settings; labels are irrelevant. But if you want to know what the term means I recommend this book over everything else you can read, including Sex at the Margins. These are not activist or academic or politician or Rescue-Industry voices: they are just human voices.

I didn’t use the term migrant sex worker in The Three-Headed Dog, although numerous of the characters can be called that. It’s a novel in which people migrate to Spain and sell sex in different ways and settings; labels are irrelevant. But if you want to know what the term means I recommend this book over everything else you can read, including Sex at the Margins. These are not activist or academic or politician or Rescue-Industry voices: they are just human voices.

Give it as a holiday gift to someone who doesn’t understand at all. You buy it as an ebook on Amazon; you don’t need a kindle but just tell what eformat you want it in. It is Safe For Work, no fear.

—Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist