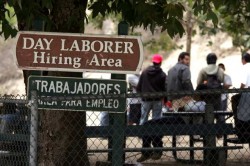

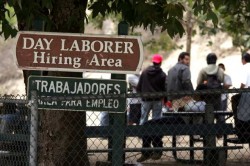

This story comes from Southall, an area of west London often called Little Punjab, but it has a lot in common with a story about mexicanos in the US called Migrant workers wait around for work and another one about algerians in France: The Suffering of the Immigrant.

This story comes from Southall, an area of west London often called Little Punjab, but it has a lot in common with a story about mexicanos in the US called Migrant workers wait around for work and another one about algerians in France: The Suffering of the Immigrant.

The migrants are called faujis, Punjabi for unauthorised immigrants. Before coming to the UK in the backs of lorries via Russia and Europe, or overstaying tourist visas, they were mostly poorer farmers from India’s Punjab region.

The following report doesn’t talk about ‘sex trafficking’, but the sense of victimisation is not dissimilar. Although the report shows different ways migrants use false papers and are used by employers, it highlights the latter. Maybe that’s a good thing for readers who think all unauthorised migrants are criminal scroungers. The reporter tells us that most of the migrants knew they were taking risks when they left home, but we need more information about that, particularly what they themselves have to say.

Migrant criminal network exposed

Migrant criminal network exposed

excerpts from BBC News 2008/07/16 By Richard Bilton

More than 40 houses packed with illegal immigrants were identified in one square mile of Southall, west London. The young, mostly male Punjabis are not here lawfully and, although most know the risks, they have few legal rights. They are surrounded by forgers, criminals and ruthless employers.

Vicki said he could get people into the country on lorries, known as donkeys, organised by what he called his “man in Paris”, and told how he could provide a fake “original” passport that had been “checked” to beat security at a UK airport.

Some try to get by without any documents. Others will have cheap, fake documents, and some will pay good money for original passports, for bank accounts, a Home Office registration card or for stolen identities on driving licences.

One reporter went [to a chip shop] for work. The owner said to “never mind” the fact he had no papers, that he would “handle that issue” and that the reporter should not mention it “otherwise you may be nicked”.

I have often recommended that we find a way to talk about this kind of migration without being forced to choose between two contrasting and simplified traps. In trap one, everyone in the story except for the reporters is flouting multiple laws and should be treated like a criminal, even though their labour is wanted and paid for in the country they’ve travelled to. In trap two, the migrants are complete victims, first of a global economy that has led them to desperate, last-ditch solutions, and then of various bad characters who have misled them about what their life abroad would be, overcharged them for fake documents, forced them to live in lousy, overcrowded conditions and underpaid them for unsafe, illegal jobs.

In Forget Victimisation: Granting Agency to Migrants, I address the second, victimising trap and I say

Of course I believe that the world is a place of terrible differences between the poor and the rich, where men almost always have more power and money. It’s not fair. But given the unfairness, I prefer to listen to how people describe their own realities rather than create static, generalised categories like Exploited Victims. I also don’t agree that poor people only leave their countries because they are forced to, with no possibility for their desires and abilities to think and weigh risks. The same goes for people who get into prostitution or sex work – I prefer to give the heaviest weight to what they say they are doing!

I see plenty of possibilities for exploitation in the fauji story the BBC tells, but I also see the kind of opportunities thousands of migrants have told me they want to take advantage of. Even though they didn’t fully comprehend how difficult it would be before they left, now they want to make the best of it. And even though they engaged in something illegal in order to cross the border, many are now eager to become useful, regular residents with both responsibilities and rights. Including some of those who sell sex, which is not mentioned in this BBC article but is not unknown in the fauji world.

There isn’t going to be one legal model for dealing with the many different kinds of quasi-legal, semi-illegal and egregiously illegal migration – of which trafficking and ‘sex trafficking’ are part. Current political rhetoric seems to imagine only two possible ‘solutions’: a hard-line, mean, law-and-order KEEP OUT policy or a soft-line, generous, utopian NO BORDERS policy. Since these reflect deeply contrasting world views, most of the debate about them remains abstract, symbolic and confrontational – as though a fundamental ‘way of life’ were at stake.

This has a lot in common with debates about the sex industry, in which two sides representing two different world views are opposed. What I’d like to see in both areas is more pragmatism about what workable improvements – not solutions, for now – might look like.

Some related posts on the different sorts of irregular migration include: